A generation under Soviet control made its voice heard on tape. UNC music scholar Andrea F. Bohlman is listening.

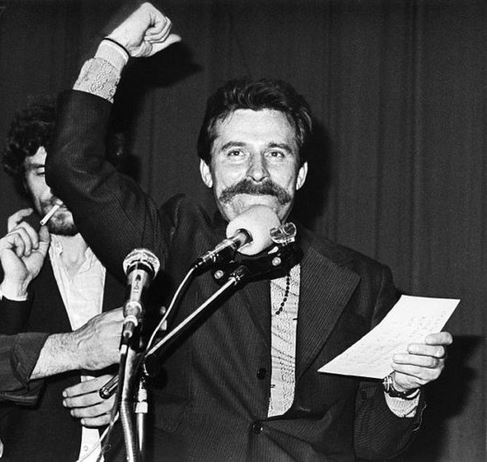

On August 14, 1980, angry dock workers gathered at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland. The firing of crane operator and labor advocate Anna Walentynowicz spurred them to march. It was the latest in a series of protests that had shaken the country that summer as prices rose, wages stagnated, and conditions for workers worsened.

The demonstration lasted into early September and led to the formation of Solidarność (Solidarity) — the first labor union free from Communist control in the Eastern Bloc. It was the beginning of a nationwide popular movement, leading to free elections in Poland and the eventual ascension of Solidarity’s founder, Lech Wałęsa, to the presidency in 1990.

The strikers knew the risks involved. Just 10 years earlier, the army and police had opened fire on a protest that began at these same shipyards, killing approximately 40 people. In the national memory of the Polish people, the demonstrators drew courage from singing “Mury” (“Walls”), a popular protest anthem by Jacek Kaczmarski:

He was inspired and young, they countless many.

Giving them strength through song, he sang of a nearing dawn.

They lit thousands of candles for him, smoke rose up above their heads.

He sang that it was time for the wall to fall…

They sang together with him:

Tear out those fang-like bars from the walls!

Break your chains; shatter the whip!

And the walls will fall, fall, fall,

Burying the old world!

That a musical work can serve to galvanize a social movement is a familiar idea. Americans longing for equality have marched to such songs as “John Brown’s Body,” “Bread and Roses,” “We Shall Overcome,” and “I Am Woman.”

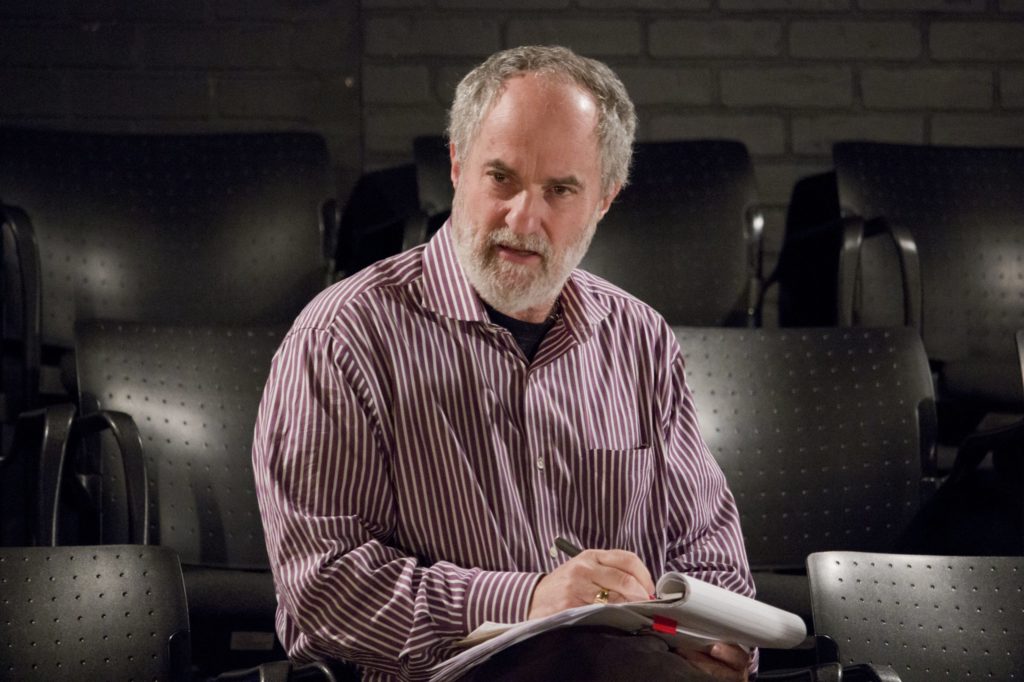

“There is certainly an idea about what a protest song should sound like that makes ‘Walls’ a good story to tell, a good story to sing, a good story to sound,” says Andrea F. Bohlman, a UNC music scholar whose work has turned an ear toward this key moment in the downfall of the Soviet Union.

There’s just one problem: the story isn’t true. While numerous eyewitness accounts and sound recordings exist of the shipyard protests, Bohlman has found no evidence that “Walls” — or even organized musical performance in general — was a significant feature of what happened there. Instead, the association of “Walls” with the protest seems to have begun later, after it was included at a music festival held on the first anniversary of the event.

That such a misconception can persist underscores our lack of knowledge about how sound, including music, works to unify the collective public willpower behind protest movements — or how its contributions in that respect are different from the role it plays in fostering collective memory.

At the crossroads of East and West

The role of sound in Poland’s history draws Bohlman’s attention because of the country’s unique status as a land both next door to, yet worlds away from, a favorite area of study for her fellow musicologists: Germany.

“There’s so much written about music in Germany and so much anxiety about its political position because of its Nazi past and also because of State Socialism,” she explains. But neighboring Poland spent much of the 20th century developing separately from the West because of its status as a Soviet satellite nation under the Warsaw Pact.

“There were all these composers from behind the Iron Curtain who barely made it into the textbooks that I have, which were all written during the Cold War, and that barely made it onto concert programs. And so I thought I should learn about what was going on over there.”

A lot, as it turns out. While the Nazis were quick to recognize and capitalize on the power of music as a political organizing force, the Communist government of Poland was relatively oblivious to its potency. When widespread dissent broke out in the years following the shipyard protests, the Party placed heavy restrictions on the use of paper, hoping to starve the burgeoning underground printing movement known as drugi obieg (second circulation).

But sound equipment was overlooked. And the movement was stirring in the wake of the mass adoption of a particularly democratic form of audio recording technology: the cassette tape.

Pause and rewind

Bohlman places a special emphasis on studying tape, as opposed to phonographic records and other media that have traditionally received more attention from musicologists. She finds clues about how messages were transmitted by listening — not just to the contents of these sonic documents, but also for artifacts that emerge as a result of tape’s material properties and the ways in which it is used.

“If you just listen to a tape carefully instead of taking it at face value, you start to notice things about the tape’s user, or its history — things that used to be recorded on it that you can hear beneath the surface, or the speed at which it was recorded, or the quality or fidelity of the tape. I find most tapes have a story if you just listen to them.”

This focus presents challenges. Tape is often used in ways that are meant to be ephemeral, with cassettes reused or thrown out when they have served their purpose. Many libraries long ago discarded their collections.

But it also presents unique opportunities for the historian — in no small part because of the affordances it creates for the amateur recorder. Tapes are cheap. They can be recorded and edited at home, using inexpensive equipment that can be operated by a person with little technical knowledge. They can be copied repeatedly. In the event of a raid, they can be erased using an ordinary household magnet, destroying the evidence they contain.

These features powered an underground music revolution. A generation of amateur musicians made tapes to bypass the gatekeepers of taste at record labels. Fans grew their music libraries by illicitly taping concerts and songs from the radio, then copying and sharing them. The mix tape became a bona fide means of personal expression — and a cultural phenomenon.

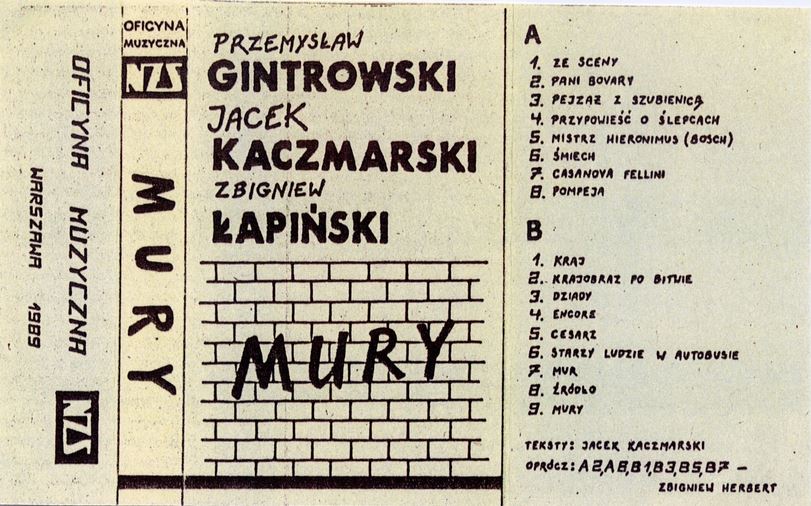

In oppressive regimes, these same qualities made tape a useful technology for dissidents looking to spread messages under the noses of censors. Bohlman has discovered that networks of cassette copying operations flourished under Polish martial law in the 1980s. Many outfits, like Niezależna Oficyna Wydawnicza (Independent Publishing House), could produce hundreds or thousands of units in each production run.

Material distributed through such networks included political speeches, music, memorials for fallen revolutionaries, and independent documentaries. One of these was “Polski Sierpień” (“Polish August”), a radio program by reporter Janina Jankowska that made extensive use of live recordings from the 1980 shipyard protests. It was from listening to documents like “Polish August” that Bohlman learned much about how sound works to unify a nation in resistance — and the very different ways it works to unify a nation in remembrance.

Come together and remember

All mass social movements require many groups within a country to rally around a common purpose or shared identity. Achieving this unity requires different factions, whose plans may vary substantially in the details, to gloss over their disagreements and move forward with a common, well-expressed goal.

Sound provides an effective vehicle for articulating such compromises and goals because of its very form. A written political text can be thousands of words and hundreds of pages long, advancing a nuanced argument permitting similarly nuanced debate and disagreement. But a song is short, structured, and to the point.

“I do think that musicians are grappling with a lot of the same questions as people who are trying to make political change. That’s what I found — that kind of messiness of the 1980s in Poland, I found it consistently to generate materials where I could see people wrestling with analogous questions across the political spectrum and within musical or sound-oriented communities. Then I am obviously interested in when those happen to be in the same place in the same time.”

There was a lot of music at the shipyards of Gdańsk in August 1980. Protesters broke into song spontaneously, and much of the music was composed on-site. Many of the songs were similar to Kaczmarski’s “Walls” in that they were sung poetry that had grown out of the Polish folk singer-songwriter tradition. But if “Walls” was ever played there, it didn’t play a major role in organizing the strikes.

Bohlman identifies the first Przegląd Piosenki Prawdziwej (Review of Authentic Song), a commemorative music festival that happened a year after the protests, as an important event in solidifying this fiction. It marks a moment when journalistic, documentarian approaches to remembering the soundscape of the protests gave way to a more deliberate framing of a nationalistic narrative. Solidarity faced many struggles in the 1980s, not the least of which was its own need to maintain unity among its different factions and devotion to a common cause. Kaczmarski, who Bohlman describes as fusing the bardic tradition of Russian song with nineteenth-century Romanticism, fit the bill of a Polish national musical hero perfectly.

But on the ground of the protests, the mechanics of performance played a much more important role in funneling group consciousness into a single bright point than either patriotism or artistic authenticity. She emphasizes that music was just one form of sound that played a role there. “How does rhythm organize protests? How do we think about the sonic atmosphere of protests? How can we think about people’s attention as a form of either unity or disunity in these moments?”

Tuning into the conversation

Bohlman’s next project will be broader in scope: She plans to reach further back in time, examining more media formats and a larger swath of Eastern Europe. The goal is to get a more comprehensive understanding of home listening and recording under Communism — including challenging the assumption that Western popular music was hard to obtain behind the Iron Curtain. She just returned from a fellowship in Berlin sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies and has a lot of material to work from.

For her groundbreaking work exploring the soundscape of the Gdańsk shipyard protests, the American Musicological Society awarded Bohlman’s essay “Solidarity, Song, and the Sound Document” the 2017 Alfred Einstein Award for Outstanding Article in Musicology by a scholar in the early stages of their career. The award cited Bohlman’s theoretical sophistication and evidence-based approach as a model of scholarship that has the potential to push the discipline in a new direction.

As part of a new generation of musical historians who focus on the sound-making practices of ordinary people, captured in home-recording media such as the cassette tape, Bohlman’s work has opened up a new vista of opportunities for potential scholarship. For her, the most important takeaway from the relationship of Solidarity to its sound culture is not that one song caused the revolution, but that the revolution was the cause of so many new songs.

“It was a historical moment that was incredibly generative on a number of levels, and I hear that in the number of different ways music was stimulated out of that moment. Both the hope and despair that people felt in the 1980s on a personal material level forced their reexamination and rearticulation of aesthetic and personal values. Music created an opportunity for conversation. Rather than celebrating its power, I would celebrate its bounty.”

Translations from Polish provided by Andrea F. Bohlman.

Andrea F. Bohlman is an assistant professor in the Department of Music within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences.

Story by Darren Abrecht, Endeavors magazine