A team of astronomers has identified possibly the coldest, faintest white dwarf star ever detected. This ancient stellar remnant is so cool that its carbon has crystallized, forming — in effect — an Earth-size diamond in space.

Bart Dunlap is a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill and one of the team members involved in the research.

“It’s a really remarkable object,” said David Kaplan, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “These things should be out there, but because they are so dim they are very hard to find.”

Kaplan and his colleagues found this stellar gem using the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s (NRAO) Green Bank Telescope (GBT) and Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), as well as other observatories.

Remarkably, neither the Southern Astrophysical Research (SOAR) telescope in Chile nor the 10-meter Keck telescope in Hawaii was able to detect it.

“Our final image should show us a companion 100 times fainter than any other white dwarf orbiting a neutron star and about 10 times fainter than any known white dwarf, but we don’t see a thing,” said Dunlap. “If there’s a white dwarf there, and there almost certainly is, it must be extremely cold.”

White dwarfs are the extremely dense end-states of stars like the sun that have collapsed to form an object approximately the size of the earth. Composed mostly of carbon and oxygen, white dwarfs slowly cool and fade over billions of years. The object in this new study is likely the same age as the Milky Way, approximately 11 billion years old.

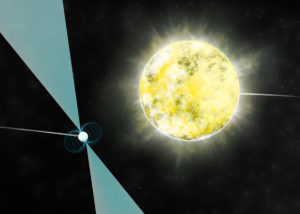

Pulsars are rapidly spinning neutron stars, the superdense remains of massive stars that have exploded as supernovas. As neutron stars spin, lighthouse-like beams of radio waves, streaming from the poles of its powerful magnetic field, sweep through space. When one of these beams sweeps across the earth, radio telescopes can capture the pulse of radio waves.

The pulsar companion to this white dwarf, dubbed PSR J2222-0137, was the first object in this system to be detected. It was found using the GBT by Jason Boyles, then a graduate student at West Virginia University in Morgantown.

These first observations revealed that the pulsar was spinning more than 30 times each second and was gravitationally bound to a companion star, which was initially identified as either another neutron star or, more likely, an uncommonly cool white dwarf. The two were calculated to orbit each other once every 2.45 days.

The pulsar was then observed over a two-year period with the VLBA by Adam Deller, an astronomer at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON). These observations pinpointed its location and distance from the Earth — approximately 900 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Aquarius. This information was critical in refining the model used to time the arrival of the pulses at the earth with the GBT.

By applying Einstein’s theory of relativity, the researchers studied how the gravity of the companion warped space, causing delays in the radio signal as the pulsar passed behind it. These delayed travel times helped the researchers determine the orientation of their orbit and the individual masses of the two stars. The pulsar has a mass 1.2 times that of the sun and the companion a mass 1.05 times that of the sun.

These data strongly indicated that the pulsar companion could not have been a second neutron star; the orbits were too orderly for a second supernova to have taken place.

Knowing its location with such high precision and how bright a white dwarf should appear at that distance, the astronomers believed they should have been able to observe it in optical and infrared light.

The researchers calculated that the white dwarf would be no more than a comparatively cool 3,000 degrees Kelvin (2,700 degrees Celsius). The sun at its center is about 5,000 times hotter.

Astronomers believe that such a cool, collapsed star would be largely crystallized carbon, not unlike a diamond. Other such stars have been identified and they are theoretically not that rare, but with a low intrinsic brightness, they can be difficult to detect. Its fortuitous location in a binary system with a neutron star enabled the team to identify this one.

A paper describing these results is published in the Astrophysical Journal.

The SOAR Telescope is a joint project of Conselho Nacional de Pesquisas Científicas e Tecnológicas CNPq-Brazil, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Michigan State University and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, a division of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.