In a Maymester course, Carolina students examined the bonds between humans and dogs that are so familiar in Western culture but have neither been practiced worldwide nor for very long over the course of human history.

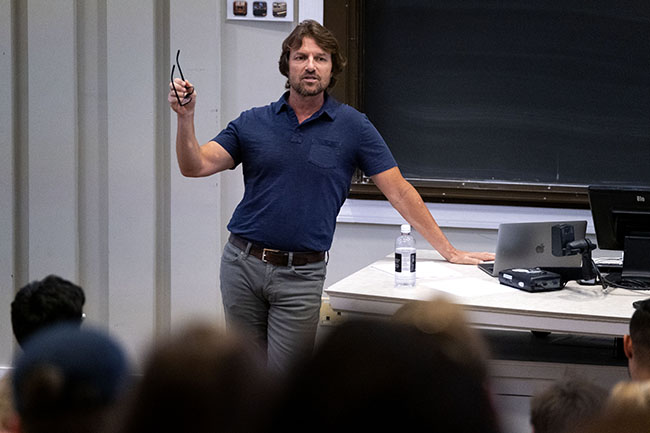

A dog may be man’s best friend, but the relationship is far more complex than most folks think. That’s what students in a Maymester course titled Canine Cultures discovered while using sociocultural anthropology research methods and concepts.

Taught by Margaret Wiener, associate professor in the anthropology department in the College of Arts & Sciences, the course examines the bonds between humans and dogs that are so familiar in Western culture but have neither been practiced worldwide nor for very long over the course of human history.

“What is our task in this class?” Wiener asks in the first session. “We will make the familiar strange by challenging common-sense assumptions—that all dogs are pets, for instance, or that dogs are necessarily better off in that role—as well as by discovering that dogs experience the world in ways humans do not; and make the strange familiar, by learning about how free-roaming dogs weave in and out of human lives in much of the world.”

Wiener tells the students that they will use tools of anthropology to examine the complexity of something they experience in everyday life. Although the Latin name for dog (Canis familiaris) can mean “family wolf” or “domesticated dog,” most dogs around the world have loose or no affiliation with humans, Wiener said. But in this class, nearly everyone has a pet dog and shares a story or two or three during the first meeting. With this lighthearted beginning, the class moves into two weeks of daily three-hour classes in which they study:

- How dogs relate to humans and how humans shape dogs’ lives;

- Services that dogs have performed;

- How colonialism, nationalism and other historical and contemporary processes that sort humans by race, gender and class have affected dog breeds and the spread of Western dog-keeping practices; and

- How art, films, monuments and other cultural products such as dog toys portray and influence human-dog relationships.

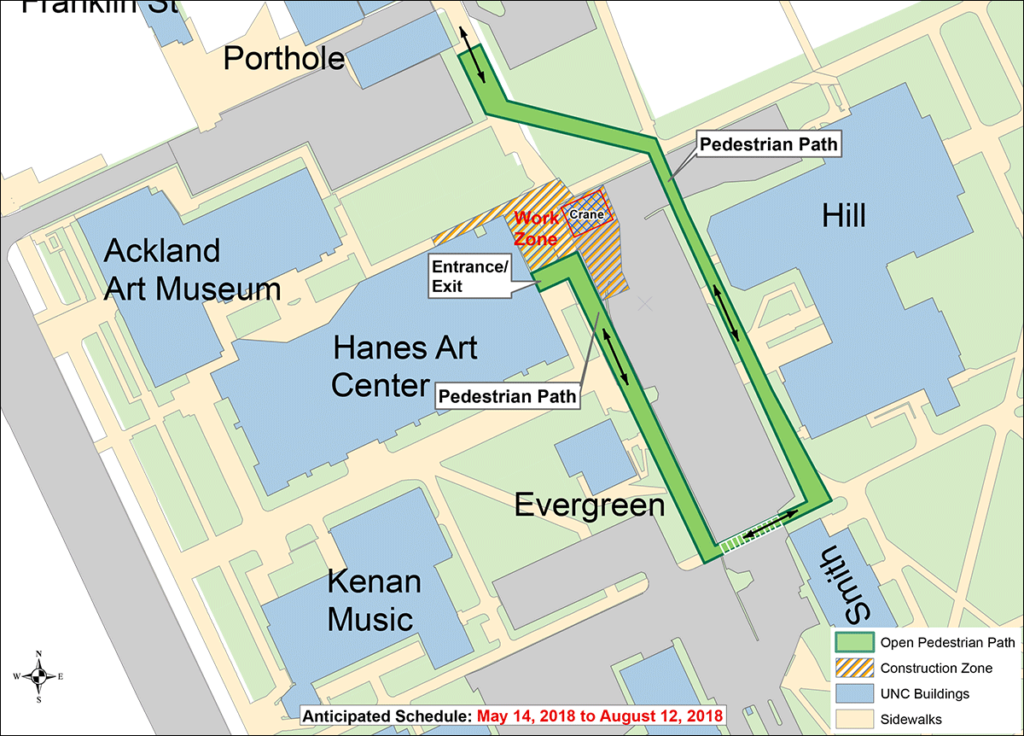

Some days, they spend a few minutes searching for people walking dogs on campus. The goal is to make field notes or sketches of human-dog interactions. As they walk, Wiener talks with individual students about their findings and their thoughts on the issues they are discussing and some conflicting opinions about the issues.

“They are willing to move beyond the fun to the thinking at every turn!” Wiener said.

In addition to gaining a practical understanding of some key concepts and practices of sociocultural anthropology, the class also:

- Collects data by observing people and dogs through fieldwork;

- Discusses and analyzes dog-human relations;

- Learns from varied readings, a podcast, scholarly articles, movies, documentaries and a visit to the University’s Ackland Art Museum;

- Learns about how dogs see, their intelligence, and about working dogs, from sled and herding dogs to the relatively new canine culture of service dogs, as well as Russian Metro and space dogs; and

- Discusses dogs as property, family members and companions.

One class featured a visit from FRANKLIN, a facility crisis response dog, and Patrol Officer Ray Rodriguez of UNC Police. FRANKLIN, a friendly chocolate Labrador retriever, trained as an assistance dog through paws4people. The students learned about FRANKLIN’s work as a service dog, while throwing a tennis ball and playing with him.

“Petting a dog and throwing the ball was a great break from the discussion we were having about different ways of knowing in primates and canines, which led me to write ‘epistemological’ on the board, and to again emphasize that the imaginative leap from our own taken-for-granted can be done by means of the alien species with which we share our homes,” Wiener said.

On another day, support dog Posey from UNC PAWS (Peer Assisted Wellness Support) and coordinator Sunny Westerman joined the class to share how UNC PAWS emotional support dogs help people with chronic conditions.

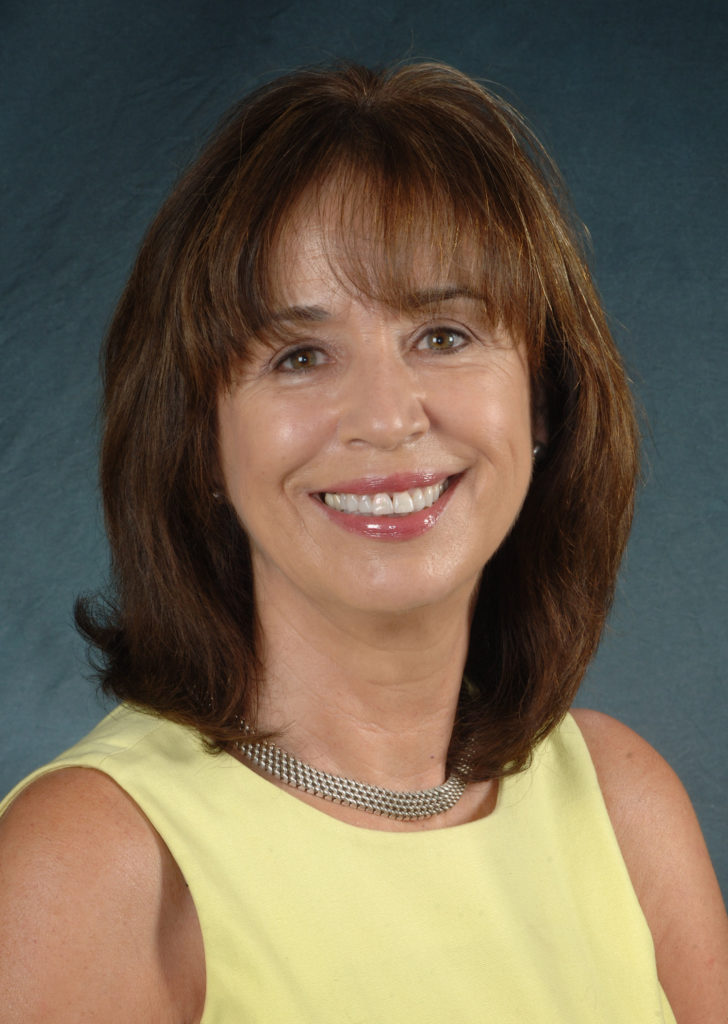

A crucial part of the course includes a web page with research resources created by Carolina librarian Jacqueline Solis. Solis, the director of research and instructional services, talked at length with Wiener about the course’s goals and what work the students would produce. The page is a gateway to many resources, including a digitized art collection and a variety of data reports.

“It’s a content management system to help the students navigate the millions of options in the library,” she said. Solis said that she wanted to fulfill the librarian’s role as an intersection of different resources from across campus, which she did before creating the page. “Actually, Margaret and I were talking and officer Rodriguez and FRANKLIN walked by, so I was able to introduce them,” Solis said.

As Maymester nears its end, anthropology major Kyle Hall said, “This class has surpassed my expectations. We probably can’t do more as far as using sociocultural anthropology tools, and the course has challenged some of our pre-conceived notions about dogs and how we interact with them.”

The course culminates with student presentations on their research, which might be stressful for some students. Not so in Canine Cultures, where an almost daily dose of wagging tails and fur therapy keeps everyone calm and relaxed.

By Scott Jared, University Gazette