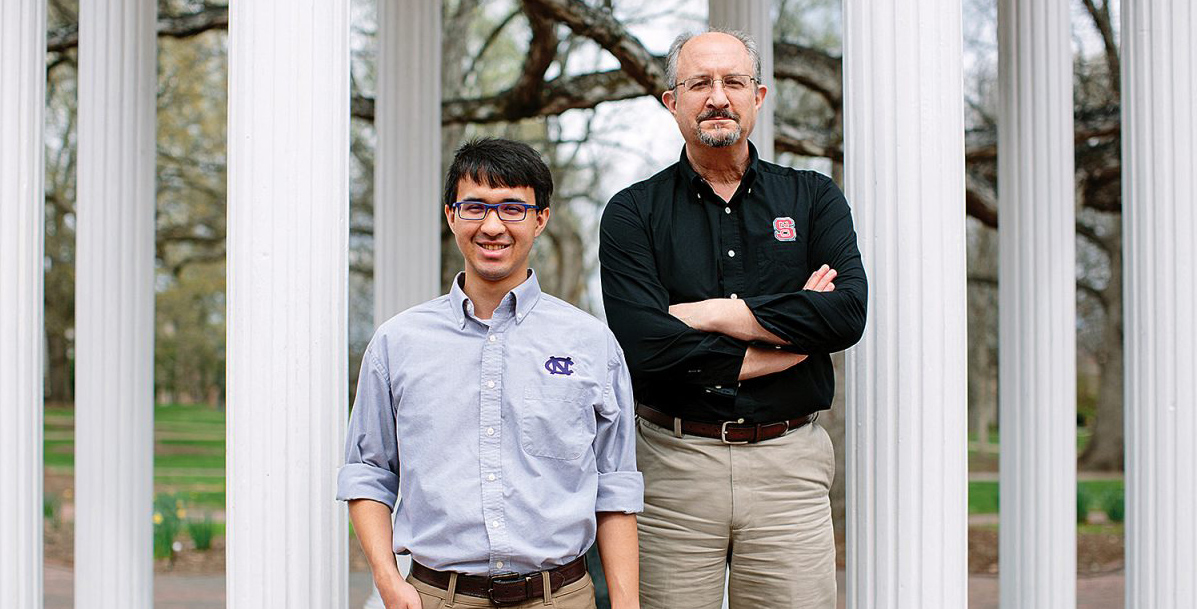

The father should be dead. The son struggled with college. They took different paths, at different schools, to an academic convergence that’s just the beginning for both. They’ll graduate together in May.

Tim Calhoun’s wife, Linda, awoke in the middle of the night, startled. She tried to wake him. Nothing. Tim’s heart had stopped. Sudden cardiac death. Linda called 911, started CPR and phoned a neighbor — a nurse who ran over to work on Tim. His heart would not restart. EMTs arrived and continued CPR until they reached the hospital. There, at Wilmington’s New Hanover Medical Center, doctors finally got his heart pumping on its own.

Tim, 42, drifted into a coma. Linda, a cardiologist, knew that few people survive sudden cardiac death; when they do, they often have severe brain damage. For days, Tim remained unconscious. Linda called in a colleague, a neurologist, and — surrounded by the best medical equipment money could buy — the neurologist took a Q-tip, stuck it inside Tim’s nose and wiggled it around.

A minute later, Tim woke up.

“I should be dead,” said Tim, now 56, a confident, gregarious man, whose heart — according to all that is known about medical science — must have stopped beating just before his wife woke. Tim’s brain suffered very limited damage.

“When I type, I interchange words. I can’t quite do calculations as fast as I used to. But otherwise, I’m the same as I was. Except that when you have an experience like that, you think, ‘Why did my wife just wake up in the middle of the night? Why do I not have brain damage?’ You start to think, ‘OK, what am I supposed to do with the rest of my life?’ ”

His son was 8 at the time. “If I had known how serious it was, I would’ve been devastated,” said David Calhoun. “But all I knew was my dad was in the hospital for a little while.”

Quiet and unassuming, David grew up wanting to please his parents, and his dad, at least, knew how David could do that. Since the day David was born, Tim had his son’s life mapped out: He would go to Carolina. He would go to medical school. He would be a dermatologist. The pay would be good, and so would the hours.

“I went along for a while,” David said. And as Tim returned to work at a pharmaceutical company, David continued to get great grades, though he wasn’t a good student.

“I would stay up all night trying to figure out how to recode video games more to my liking. I’d be so exhausted I could barely stay awake in class the next day.”

It was at David’s orientation at Carolina in 2013 that Tim discovered what he wanted to do with the rest of his life: be part of a team that creates devices that help people, devices like the implantable cardio defibrillator in his chest. He quit his job and enrolled at a community college with an eye toward transferring to a four-year university.

David succeeded in AP high school courses because he’d memorize everything the night before an exam. His grandfather had had a photographic memory, and some of those genes apparently made their way to David. But in college, David’s nocturnal habits caught up with him. Learning required more than memorizing.

It was at David’s orientation at Carolina in 2013 that Tim discovered what he wanted to do with the rest of his life: be part of a team that creates devices that help people, devices like the implantable cardio defibrillator in his chest. He quit his job and enrolled at Cape Fear Community College with an eye toward transferring to a four-year university.

Rocky start at Carolina

Meanwhile, David went to Carolina. And almost immediately, he knew he wasn’t ready.

“I wish, back in high school, I had the courage to tell my parents I needed a gap year or two before I went to college,” said David, 23. “My maturity just couldn’t catch up with my academics. I just wasn’t emotionally prepared for college.”

He didn’t know it at the time, but he has Asperger’s syndrome, which puts him on the autism spectrum. He’s highly intelligent. He articulates his words precisely. He maintains eye contact. But some social interactions don’t come easy — people with Asperger’s repeat behaviors. As David sits, his knee bounces up and down. He answers every question authentically, without a beat of hesitation.

He missed the 2014 fall semester with an intestinal infection. He returned in the spring, and he struggled in anatomy and physiology. This is when he knew he would not become a doctor. As part of his biomedical engineering major, he took a class called biological measurements, the technicalities of which he greatly appreciated, as he did his professors. But his experience at Carolina still wasn’t easy. Typical dorm life bugged him. He couldn’t get his sleep on track. He seemed out of fuel, out of sync.

As David struggled, his dad had excelled at Cape Fear, and N.C. State’s biomedical engineering program had accepted him.

Since 2003, the UNC/N.C. State Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering has blended the liberal arts and biomedical science strengths at Chapel Hill with top-tier engineering faculty and programs at State. Both are strong in computer science. BME students are given access to state-of-the-art equipment and facilities at both. It’s a unique relationship that offers students a lot of opportunities for research, collaboration, coursework and consultation with some of the country’s top experts in various fields.

“These students are all so much smarter than me,” Tim said. “I’ve had to work twice as hard just to keep up. But I know that’s my strength. No one will out-work me. In fact, David will tell you, he’s smarter than me, but I’m a better student.” David concurs with that, unsolicited.

“I want people to know how incredible this BME department is. It’s tough. … The professors are demanding and amazing. These students here are brilliant; national companies should be recruiting them. As for me, hopefully this degree will get me into a circle of professionals that improves the human condition.”

— Tim Calhoun ’18

Tasked with making a rudimentary rotating chamber, Tim was the only member of his class to get the chamber to rotate. “That wasn’t part of the assignment,” he said, “but I just had to see it rotate. That’s just how I am.”

Tim earned the department’s Citizen and Service Award for establishing department partnerships with Medtronics and Duke University Hospital, among other projects. While his wife stayed in Wilmington for her work, Tim became entrenched at N.C. State, living in a dorm and connecting with students a generation younger. And David’s junior year fell apart. Since high school, David never readjusted his sleep patterns or nighttime routine, which he augmented with coffee. One night, a panic attack landed him in the ER. A few weeks later, sleep deprived, he was back there.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but I can’t metabolize caffeine. I’ve since been tested. I should never have been drinking coffee, let alone at night.”

The path turns parallel

Demoralized, he took another semester off and convinced himself he could not get through school. He needed solitude. He called Belmont Abbey near Charlotte to inquire about becoming a monk. His mom, trying to talk him out of it, asked a colleague to evaluate her son.

“The doctor told me my brain was like a Ferrari with crappy tires,” David said. “My memory was shot.”

During that semester off, David quit caffeine and normalized his sleep patterns. His outlook brightened. He reconsidered his monastery idea and instead returned to Carolina, where nothing was quite as difficult anymore. His brain’s tires had some tread.

Something else synced: His dad was no longer a semester behind him. They were on track to graduate together.

Through it all, David maintained a GPA approaching 4.0. As Tim pushed assignments beyond the required, David was project manager of his senior design team — essentially the quality engineer who makes sure proper protocols are followed according to standard operating procedures. David loved it. He’s eyeing internships at companies specializing in quality control and regulatory compliance for medical devices.

Tim, meanwhile, chugged tirelessly through the biomedical engineering curriculum, working long hours in the lab while volunteering 5 a.m. to 9 a.m. every Monday at the hospital at Duke. His high grades earned him admittance into Tau Sigma, a national honor society for university transfer students, and his work ethic earned him the respect of students and faculty.

In a large lab, Tim created a dedicated space surrounding a state-of-the-art 3-D printer, which he and other students use to create all kinds of things, including prosthetic hands for the Helping Hand Project — a nonprofit student organization that creates individualized plastic hands for kids who need them but whose families can’t afford them.

David, who is part of UNC’s Helping Hand Project team, has noticed his dad has mellowed out over the past few years, despite Tim’s boundless enthusiasm for all things BME. Although David grew to appreciate the college experience, he’s ready to move on. No graduate school for him. Not yet.

“I want to be an adult. I want to work.”

Though Tim’s story starts at the moment he died, his new life began with the BME program.

“I want people to know how incredible this BME department is,” he said. “It’s tough. I could never just take a weekend off and go back to Wilmington. The professors are demanding and amazing. These students here are brilliant; national companies should be recruiting them. As for me, hopefully this degree will get me into a circle of professionals that improves the human condition. I don’t have to work with patients. If I’m part of a company that makes a device that helps patients — and that device has to be excellent — that will be good enough. I got maybe 20 more years left, tops. I want to make them worthwhile and not just for me.”

Graduates of the program receive diplomas with the seals and signatures of both universities.

Though BME has been around for 15 years — teaching graduate students and faculty doing research — there was no joint undergraduate graduating class until last year. David Calhoun ’18, who took a serpentine path, and Tim Calhoun ’18, who had to die first, are members of the second.

By Mark Derewicz, UNC Health Care and freelance writer, Carolina Alumni Review