Senior Morgan Vickers used digital tools to study the impact of the 1921 lynching of 16-year-old Eugene Daniel on a community now buried beneath Jordan Lake — and the modern-day implications for marking this site of trauma in an area where people swim, boat and play.

Graduate student Hannah Herzog’s passion for Jewish culture and history led her to interview Holocaust survivors about how they negotiated the racial landscape of the American South after settling there in the 1940s and ’50s. In the process, she uncovered her own amazing adoption story.

The 2018 American studies graduates share a common bond of uncovering the stories of people behind painful but important moments in history.

Racial trauma in a community flooded by Jordan Lake

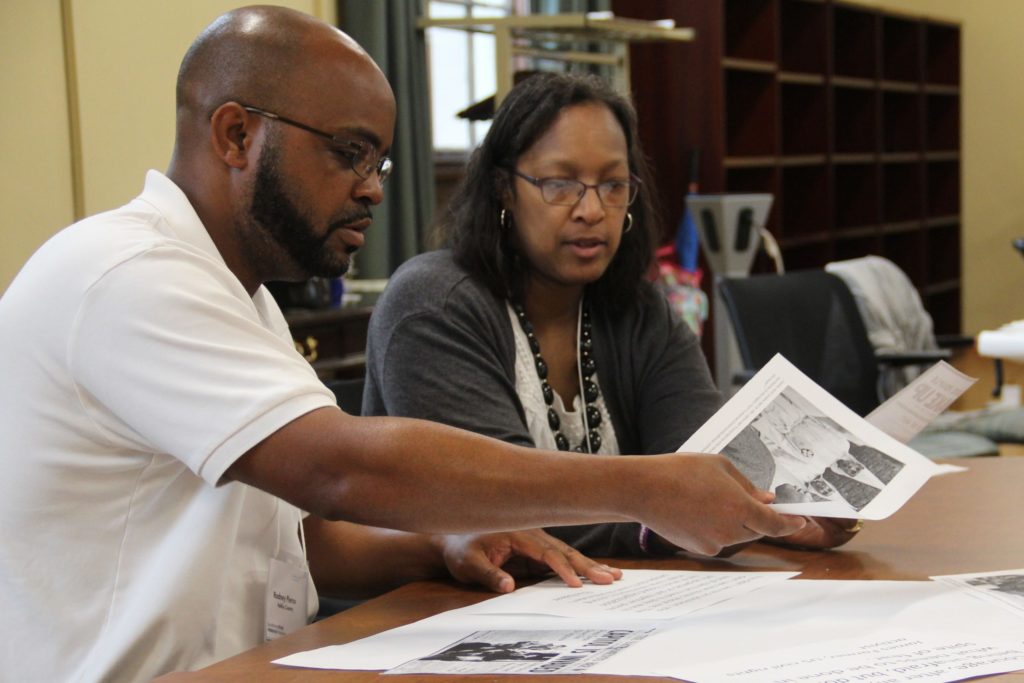

Morgan Vickers was working with Seth Kotch, assistant professor of American studies, on mapping lynchings in North Carolina through a digital humanities project called “The Red Record” when she came across something strange.

Vickers said, “I think someone made a mistake because this lynching is in the middle of Jordan Lake.” Kotch told her that was accurate because the artificial lake was created in the 1970s.

“My mind just sort of spiraled from there, and it became a quest for me to figure out what happened, to take a deep dive into that lost community,” said Vickers, who will graduate with a double major in American studies and communication studies and a minor in creative writing.

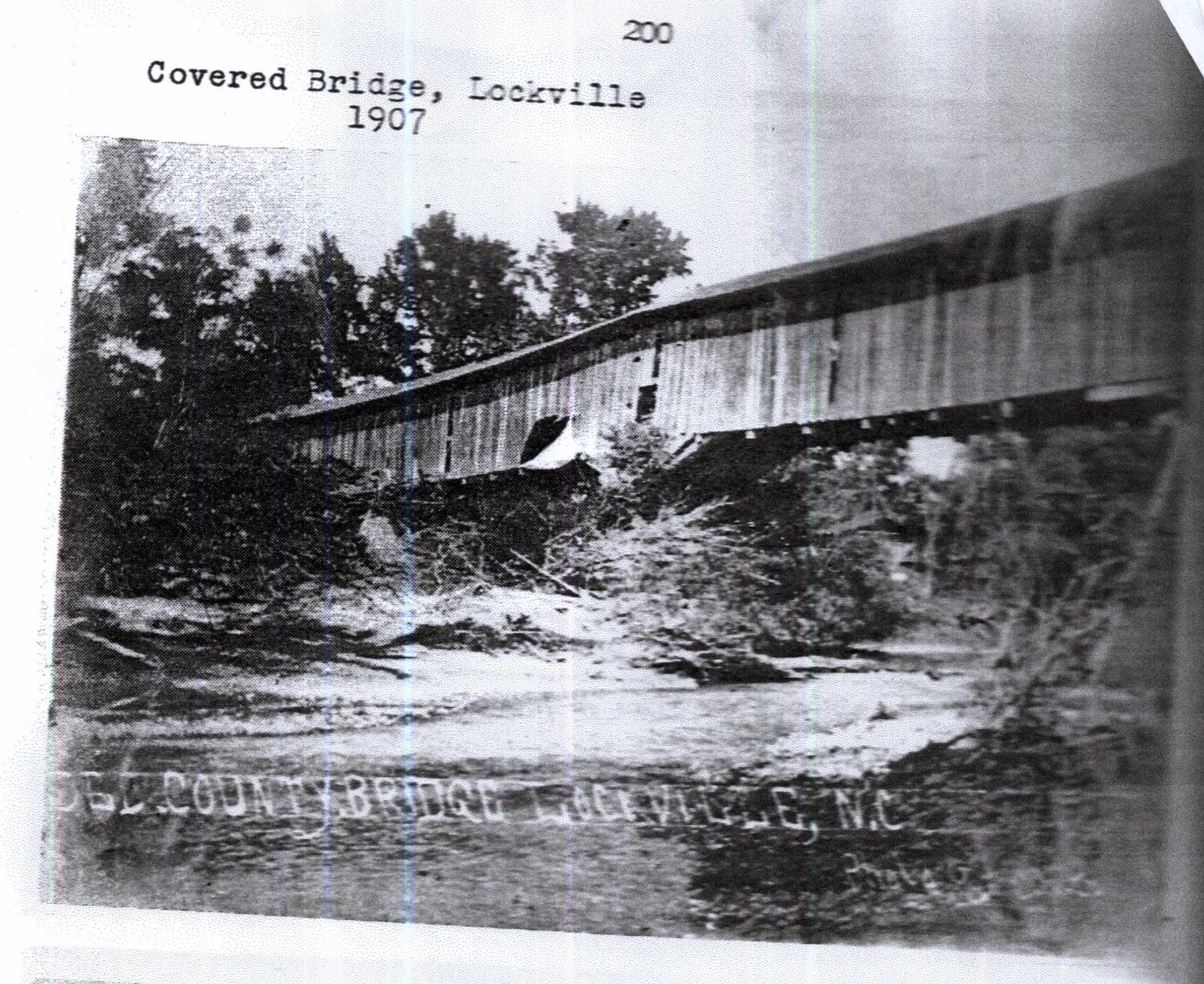

Vickers’ initial research focused on Lockville, one of four communities buried beneath the lake. It lies adjacent to New Hope Township, where Eugene Daniel was lynched. With help from a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship, she created The Lockville Project to examine the question: “While Lockville is a small, drowned ghost town in Chatham County, its legacy (or lack thereof) begs historians to ask: How do we remember history of violent trauma, if at all?”

On the project website, she wrote about transportation, communication and infrastructure in Lockville, the impact of the Civil War on the region, the town’s rich mining resources, and the state’s attempt to locate a penitentiary there.

“It was the town that could have been — an idealized community that never really came to fruition,” she said.

Vickers decided to focus her honors thesis on Daniel, whose reported crime was entering the bedroom of a neighbor, 17-year-old Gertrude Stone. She explored the impact of Daniel’s lynching on the community and both families involved. Through a serendipitous turn of events, she discovered that associate professor of anthropology Glenn Hinson had conducted interviews in 2016 with some of Daniel’s relatives as part of his class, “Southern Legacies: The Descendants Project.”

“Community members claimed they lynched Eugene Daniel to prevent future crimes from occurring, but based on newspaper accounts in the months and days after the lynching, crime did not stop,” Vickers said.

In addition to combing through newspapers, census records and oral history interviews, Vickers stumbled upon a geocache activity through a web search. “The Lynching of Eugene Daniel” leads visitors to key places in Daniel’s life.

“You go to the site of his former house, to the place where he was placed in jail and then to the supposed site where he was lynched. Because it’s underwater, you have to take a kayak to reach it,” she said. “How do you mark a site that no longer exists? What is the right way to discuss these stories?”

Vickers received numerous prizes for her research, including the William S. Powell Award from the North Caroliniana Society, and the Peter C. Baxter Memorial Prize in American Studies.

She first became turned on to digital humanities — which combines her love of history, humanities and technical skills — through American studies professor Robert Allen’s “Downtown North Carolina” class.

“Eventually I want to get a Ph.D. in American studies or history. I’ve had extraordinary professors here who have invested so much in me,” Vickers said. “I’d be perfectly content exploring the archives for years and years to come.”

A powerful connection to Jewish history and culture

“I felt this really strong connection to Jewish studies, culture and tradition that I couldn’t explain.”

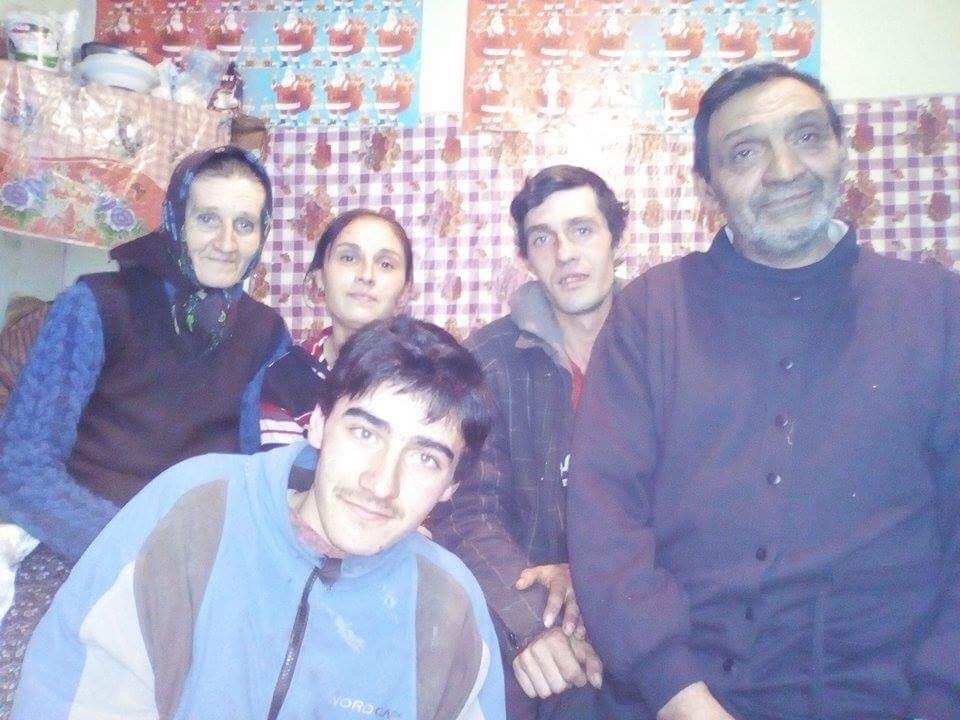

That sentiment sheds light on both Hannah Herzog’s academic and personal journey. Herzog, who grew up in Dallas, was adopted from a Romanian orphanage when she was about 3 years old. Later, as a pre-law student at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, she took a Jewish American literature course that changed the course of her academic career and led her to graduate school in the American studies department at UNC-Chapel Hill.

After the first year of her master’s program, in what she called “the most impulsive decision I’ve ever made,” Herzog contacted the organization Never Forgotten Romanian Children on Facebook. Within four days, organizers had tracked down her birth parents in Romania. Turns out, her maternal grandmother is Jewish.

“On the fifth day, I was on the phone with my birth family,” said Herzog, who is currently learning Romanian with the help of a tutor. “My sister, who is the only one with an Internet connection, messages me every day to say, ‘I love you.’”

Herzog, who will receive an M.A. in folklore, felt drawn to Holocaust studies and has received a number of fellowships and grants, including the Daniel W. Patterson Fellowship, to support her work. For her thesis, she interviewed 15 Holocaust survivors in Atlanta, Birmingham and Charleston. Their ages ranged from 78 to 95. She said Holocaust survivors who settled in the South faced a different form of anti-Semitism after fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe. Her work will be archived in museums across the South, including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

“It is through my newly discovered Eastern European family, my Jewish heritage and the trauma of my own displacement that I feel a visceral connection to those who suffered in the Holocaust,” Herzog writes in her thesis, which is divided into case studies of five survivors.

Each of the survivors’ stories touched Herzog in some way. Joe Engel wears a nametag every day that says “Holocaust Survivor.” Robert May became a surgeon at age 18 and chose to work in a doctor’s office that treated African American patients.

Hershel Greenblat told Herzog that in order to explain his first impressions of America, he could show her better than he could tell her.

“I really hope this doesn’t make me emotional,” Herzog said, as she recalled the story. “But it’s so powerful.”

“He handed me a 50-cent coin in a glass case,” she continued. “When his family got off the train in New York at 3 a.m. on Thanksgiving Day, they were completely lost, didn’t know a single word of English and needed to get to Atlanta. An American soldier helped them to find the right train, and when they departed, he gave Hershel this coin. He was 9 years old at the time and is now 89. It became his moral compass. Every day it reminds him to pay it forward, to treat others with the same kindness.”

Herzog has presented her research at both regional and national conferences and said she is grateful for the support UNC faculty have given her.

“Carolina was my dream school because of the interdisciplinary research opportunities available in American studies. My professors, especially Marcie Cohen Ferris, have guided me, encouraged me and believed in me. I think these relationships will last forever.”

By Kim Spurr, College of Arts & Sciences