In 2006, the family of Sonja van der Horst, a Holocaust survivor, established the JMA and Sonja van der Horst Distinguished Professorship in Jewish Studies, honoring her and her husband, Johannes “Hans” van der Horst. The professorship supports a distinguished teacher and scholar specializing in Jewish history or culture, and was created by their four children: Charles van der Horst, Roger van der Horst, Jacqueline van der Horst Sergent ’82, and Tatjana Schwendinger. They chose UNC because of close family ties to the state and the university. The family used Holocaust reparation funds Sonja had saved since the 1960s to establish the fund, which was supplemented with state matching funds from the Distinguished Professors Endowment Trust Fund to create the $1 million professorship.

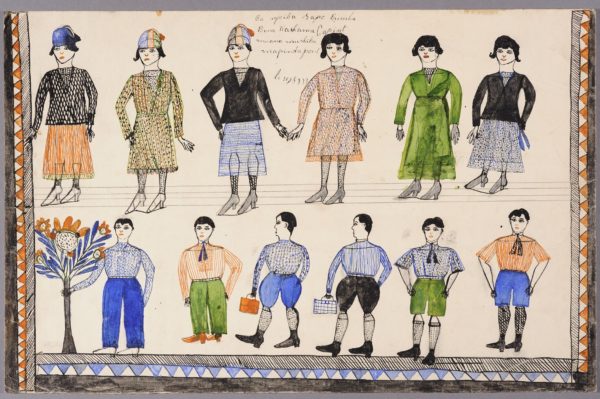

Sonja was only 15 years old when the Nazis invaded Poland. As a teenager during World War II, she was forced to live in a Jewish ghetto in her hometown of Tarnopol, where the Nazis executed her father and sister, sent her mother to die at a concentration camp and began the systematic elimination of 18,000 Jews.

Sonja survived the Holocaust by changing her name and assuming false identities after she dared a Nazi soldier to shoot her. The soldier had ordered her to leave the basement where she and her friends were hiding. When confronted, instead of shooting her, the Nazi soldier hit her on the head with the butt of his gun and left. She later learned that her mother, father and sisters were murdered by Nazis.

Sonja knew she’d have to escape Tanopol to survive, so she changed her name from Chaya Eichenbaum Teichholz to Sofia Kubasyk (and later to Sonja Tarasowa) to blend in with the Russians. Then she snuck onto a Russian train carrying non-Jewish workers to labor sites in Dortmund, Germany. For the duration of the war, she posed as a Russian laborer while working at a coal mine, a lumberyard and a farm before becoming a translator for the English forces.

Following the war, Sonja made her way to Greven, Germany, where United Nations officials were processing refugees. There, she met Johannes Martinus Arnold “Hans” van der Horst, a Dutch man who was working for the U.N. and had been a scout with the U.S. Armed Forces invasion of southern France in 1944. She spoke no English and Hans spoke no Russian. Hans was looking to learn Russian, and the two met for language lessons often.

In summer 1945, the Soviets began the forced repatriation of displaced persons to their countries of origin. Though pretending to be Russian, Sonja did not want to be deported to the Soviet Union and began preparations to go into hiding. When Sonja told Hans her story, he asked her to marry him. They were wed in the Netherlands that year and left for the United States in 1952, eventually settling in Olean, N.Y.

After the war, Hans and Sonja van der Horst spent their lives supporting organizations that promote public education, civil rights, religious freedom and Jewish culture. Hans, a chemical engineer who was fluent in seven languages, died in 1978; Sonja died in 2006.

In 2011, Flora Cassen was named the inaugural JMA and Sonja van der Horst Fellow in Jewish Studies. Cassen teaches classes on medieval and early modern Jewish history, specifically focusing on the history of Europe from the 10th through 18th centuries.

(Sources include News and Observer articles by Jane Stancill “A survivor’s enduring gift” and “Sonja van der Horst, 82, Holocaust survivor funded Jewish studies at UNC-CH,” 2006, and the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies newsletter, summer 2011.)