Critical thinking is the magic of the classroom: Facts go in, contemplation ensues and voila: perspective emerges. Undergraduate history major Andrew Vail ’99 listened as professor Theda Perdue lectured on the marginalization of Native Americans in the southeastern United States. Education became the impetus.

“I recall being in Dr. Perdue’s class and learning about these grave social injustices in our history,” Vail said. “It crystallized for me that I wanted to make a commitment to social justice. My Carolina education made that commitment concrete and propelled me to carry through.”

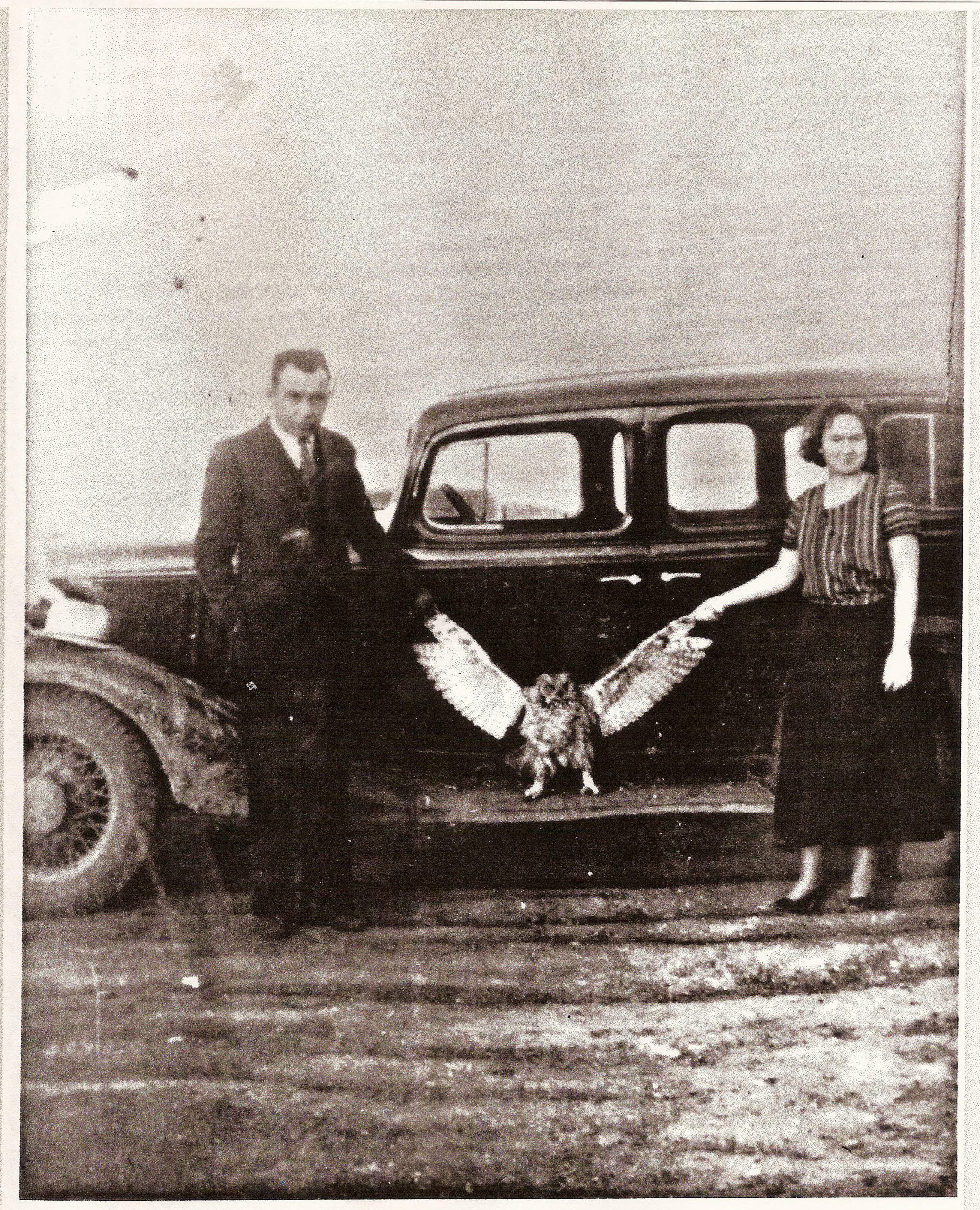

Now a practicing lawyer at Jenner & Block LLP in Chicago, Vail carried through by establishing the Henry Owl Scholarship Fund for Undergraduate Students, honoring the mettle of Henry Owl ’29, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the first person of color to be admitted to –– and graduate from –– the University. An endowed scholarship, it will provide need-based funds to one or more undergraduate majors in the department of American studies, with preference to students in American Indian and indigenous studies. Vail learned about Henry Owl after graduation through correspondence with now-professor emerita Perdue and her husband, late professor emeritus of American studies, Michael D. Green. What Vail learned inspired him.

“My major concentration was in Native American history, so I felt an immediate connection to Owl’s background,” he said. “The distinction of being the first person of color to get a degree from Carolina is extremely significant and something that should be recognized. Also, Owl’s lifelong dedication to education –– to building a better life for himself, his family and community and those around him –– it all struck a chord in me.”

Born in Swain County, N.C., at the foothills of the Appalachians, Henry Owl grew up in the Qualla Boundary. He followed his father, Lloyd, to the reservation’s boarding school, then to Hampton Institute in Virginia –– now Hampton University –– a historically black school that until 1923 offered an industrial training program for Native Americans. One of the classes taught at Hampton was “Gumption.”

“The point of the class was character-building –– to instill a sense of getting up and going after life instead of waiting for life to happen,” said Gladys Cardiff, Owl’s daughter. “It clearly worked. [My grandfather and father] all aspired to a broader education and a broader vision of what the world had to offer.”

Attaining such an education wasn’t easy. After Hampton, Owl worked several jobs to earn tuition to Lenoir-Rhyne College (now University). He graduated with a history degree, then worked his way through Carolina, earning his M.A. in history with the thesis, “The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Before and After the Removal.” Every degree is important, but Owl’s thesis, more so.

Denied the right to vote on grounds that Indians were illiterate, Owl presented his UNC-Chapel Hill master’s thesis to the county voting registrar. Denied a second time on grounds that Cherokees were wards of the government and not U.S. citizens –– in opposition to a 1924 law –– Owl testified before Congress, which responded with a law guaranteeing the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians citizenship and the right to vote.

Largesse of intellect, beneficence of achievement: Henry Owl inspired Andrew Vail, who will, in turn, inspire others.

“Carolina’s American Indian and indigenous studies community celebrates the Henry Owl Scholarship Fund for Undergraduate Students,” said associate professor Daniel M. Cobb, coordinator of the American Indian studies major and minor. “Mr. Vail’s generosity complements our long-standing strengths and bolsters our ongoing efforts to deepen our relationships with American Indian communities in North Carolina. We are very grateful.”

[ By Chrys Bullard ’76 ]