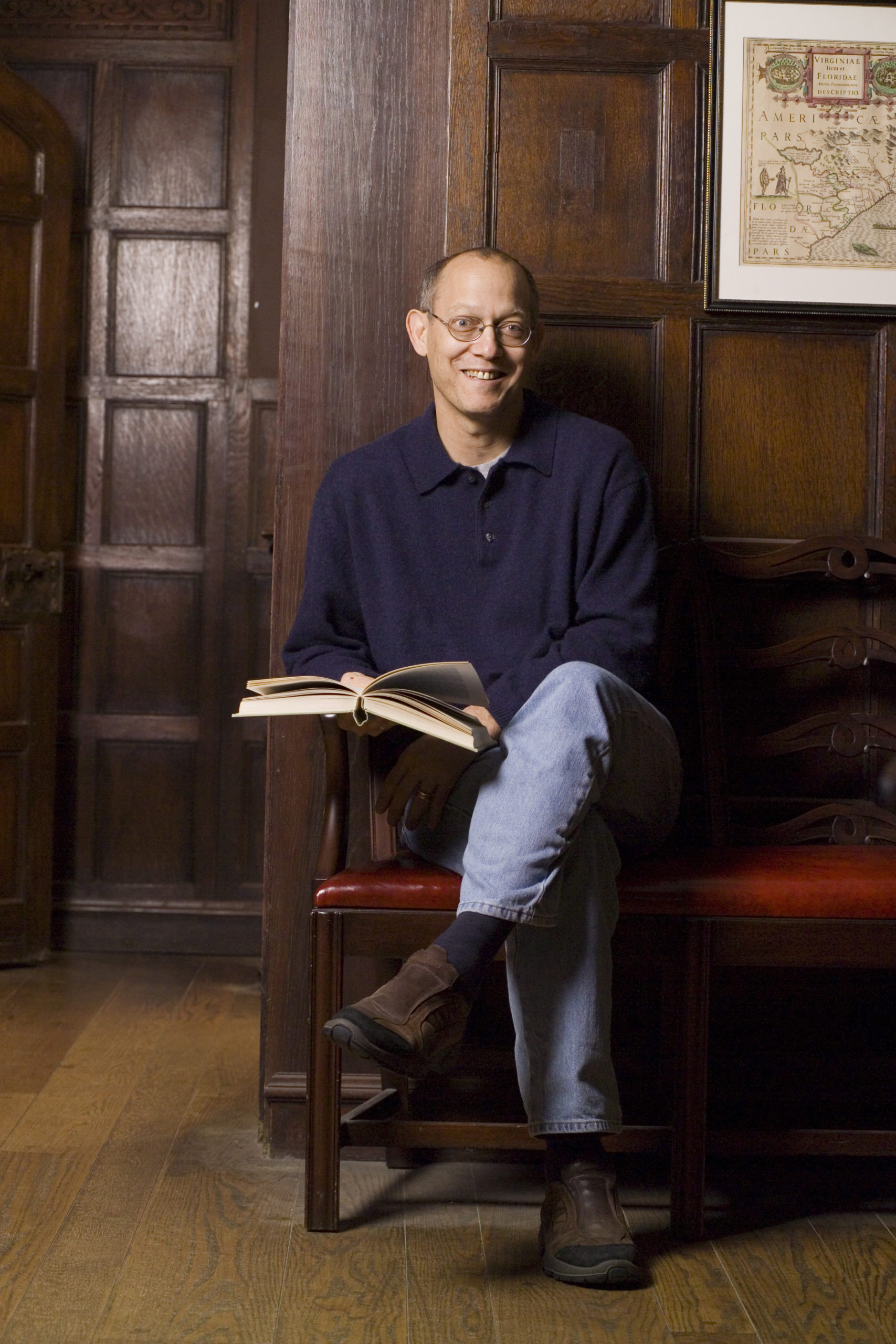

Alan Shapiro, Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing in the College of Arts and Sciences, will receive a North Carolina Award for Literature at a ceremony on Nov. 13. The awards, given for literature, public service, science and fine arts, are the highest civilian honor in the state. Shapiro is the author of 12 books of poetry (including Night of the Republic, a finalist for both the National Book Award and The Griffin Prize), two memoirs, a novel, a book of critical essays and two translations. He shares what this award means to him, how poetry is the perfect outlet for exploring difficult topics, and why, decades later, he still loves teaching at Carolina.

Read the poem, “Coffee Cup,” from Shapiro’s Night of the Republic.

Q: Congratulations on winning a North Carolina Award for Literature. You’ve received many accolades for your work, including the state’s highest prize for poetry, the Roanoke-Chowan Award — twice. What does this particular award mean to you?

A: Well, Truman Capote once said, “It’s a long walk between drinks.” This is certainly a very nice drink. I’ve lived in North Carolina longer by far than I’ve lived anywhere else in my life. I raised my children here. So, to receive this recognition from what I consider my home state is very sweet. The community of fellow writers is one of the most if not the most inclusive and generous I’ve ever encountered. That someone whose ties to the state go back only two decades could win an award like this is a measure of just how welcoming the writers and the people of this state have been and continue to be.

Q: You’ve written poetry, memoirs, critical essays, translations and a novel. Why has it been important to you to cross genres and not just concentrate on one thing?

A: There are things one can say in a poem that one can’t say in a novel, and things one can say in a novel that one can’t say in a memoir. Each form, like a lens, brings some aspect of life and language into focus while excluding others. As a writer I want to live throughout the whole range of my faculties and sensibilities in relation to the widest range of life — to bring, in other words, as (Samuel Taylor) Coleridge says, the whole soul into activity. I think my interest in working in different genres stems from my desire to be as open and inclusive as I possibly can be, so that each thing I write, in whatever form, is its own reckoning with life and language.

Q: You have taken on difficult topics in your poetry — losing siblings to cancer, aging parents and more. What is it about poetry that makes it a good medium to explore these complex, intimate and emotional topics?

A: Poetry is our oldest technology of feeling. To paraphrase (Matthew) Arnold, it finds the best words, the most memorable words, for the most difficult or complex or vital experiences. To celebrate, lament and resist in the most unforgettable language. Do you remember the movie Contact with Jodie Foster? Remember when she travels through that galactic worm hole and sees that incredibly beautiful alien planet for the first time? What are the first words out of her mouth? “They should have sent a poet!” Imagine how flat and silly she would have sounded if she’d said, “They should have sent a journalist.” Or “They should have sent a creative nonfiction writer.” Best words for the most significant moments — that’s what poetry is and does.

Q: The UNC department of English and comparative literature has quite a history of wining North Carolina Awards for Literature — Doris Betts (1975), Louis D. Rubin Jr. (1992), Elizabeth Spencer (1994), Jill McCorkle (1999) and Randall Kenan (2005). In 2005, Bland Simpson also won the North Carolina Award in Fine Arts. Is there something in the water at Greenlaw?

A: See my answer to the first question. I have been blessed with amazing friends and colleagues — and with students who have gone on to be become first rate poets and writers. The state is full of great writers and has been for a long time, and some of the best of them come out of UNC. Everyone in our program makes everyone else around them better. Which is to say that yes there is something in the water.

Q: You’ve been teaching at Carolina since 1995. What is it about teaching that is still exciting, and what do you learn from your students?

A: I think all writers have to feel at every point of his or her career that they have everything to learn, that they must always be pushing against the limits of what they know how to do. Once you feel as if you’ve mastered the art, you’re finished, washed up, however happily deluded you might be. What I love about teaching is that the students remind me constantly of where it is I have to be — and how to be there, with everything to learn. We are all students, some just older and bit more experienced than others. To continue to grow you can’t forget that. Not letting me forget that has been the great gift my students have given me. And it’s just as valuable and exciting now as it was 38 years ago when I taught my first creative writing class at Stanford.

— Interview by Kim Weaver Spurr ’88