An international team, including Christoph Baranec of the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Institute for Astronomy and Nicholas Law of UNC’s College of Arts and Sciences, is using the world’s first robotic laser adaptive optics system — Robo-AO — to explore thousands of exoplanet systems (planets around other stars) at resolutions approaching those of the Hubble Space Telescope.

The results, which shed light on the formation of exotic exoplanet systems and confirm hundreds of exoplanets, have just been published in the Astrophysical Journal. The design and operation of the unprecedented instrument has just been published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Law with UNC’s department of physics and astronomy is Robo-AO’s project scientist and lead author on the Astrophysical Journal paper. Carl Ziegler from UNC is also a member of the Robo-AO team.

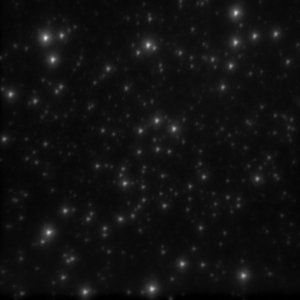

Laser adaptive optics systems are used by terrestrial telescopes to remove the image-blurring effects of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere, thereby capturing much sharper images than are otherwise possible from the ground. Baranec, Robo-AO’s principal investigator and lead author of the Astrophysical Journal Letter, led the development of the innovative Robo-AO system on the Palomar 1.5-meter telescope. It is the world’s first instrument that fully automates the complex and often inefficient operation of laser adaptive optics.

“We’re using Robo-AO’s extreme efficiency to survey in exquisite detail all of the candidate exoplanet host stars that have been discovered by NASA’s Kepler mission,” said Baranec. “While Kepler has an unrivaled ability to discover exoplanets that pass between us and their host star, it comes at the price of reduced image quality, and that’s where Robo-AO excels.”

In fact, analysis of the first part of the Robo-AO/Kepler exoplanet host survey is already yielding surprising results.

“We’re finding that “hot Jupiters” — rare giant exoplanets in tight orbits — are almost three times more likely to be found in wide binary star systems than other exoplanets, shedding light on how these exotic objects formed,” said Law. “Going further, Robo-AO’s unique capabilities have allowed us to discover even rarer objects: binary star systems where each star has a Kepler-detected planetary system of its own. These systems will be uniquely interesting for studies of how the planets formed — and for science fiction about what life would be like with another planetary system right next door.”

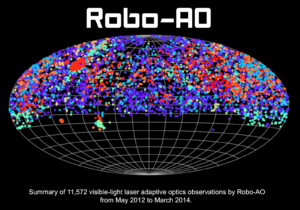

Indeed, the first Robo-AO survey, covering 715 Kepler candidate exoplanet hosts, is the single largest scientific adaptive optics survey ever. That record won’t stand for very long, as the Robo-AO team is extending the survey to image each and every of the 4,000 Kepler candidate exoplanet hosts, and is ready to observe exoplanet hosts from Kepler’s new K2 mission as they are discovered.

The key to Robo-AO’s success is its efficiency, allowing it to observe hundreds more targets per night than conventional adaptive optics systems. So far, the Robo-AO system has already been used to make over 13,000 observations.

“The automation of laser adaptive optics has allowed us to tackle scientific questions that were unimaginable just a few years ago. We can now observe tens of thousands of objects at Hubble-Space-Telescope-like resolution in short periods of time,” Baranec said. “Now that the technology has been proven, we’re looking to bring it to the pristine skies of Maunakea, Hawaii, where it will be even more powerful.”

Other members of the Robo-AO team are Timothy Morton (Princeton), who interpreted the implications of Robo-AO observations for the candidate Kepler exoplanets; Reed Riddle (Caltech), who coded the Robo-AO software system; Ganesh Ravichandran, a student at W. Tresper Clarke High School, Westbury, New York; Kristina Hogstrom, Khanh Bui, Richard Dekany, Prof. Shri Kulkarni, and Shriharsh Tendulkar (Caltech); John Johnson (Harvard); and A. N. Ramaprakash, Mahesh Burse, Pravin Chordia and Hillol Das (Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Pune, India).

Founded in 1967, the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii at Manoa conducts research into galaxies, cosmology, stars, planets and the sun.