Individuals in Latin America with darker skin color are at higher risk for poor health and discrimination, according to a new study led by researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Princeton University.

It is the first cross-national study to examine the association between skin color and health in Latin America.

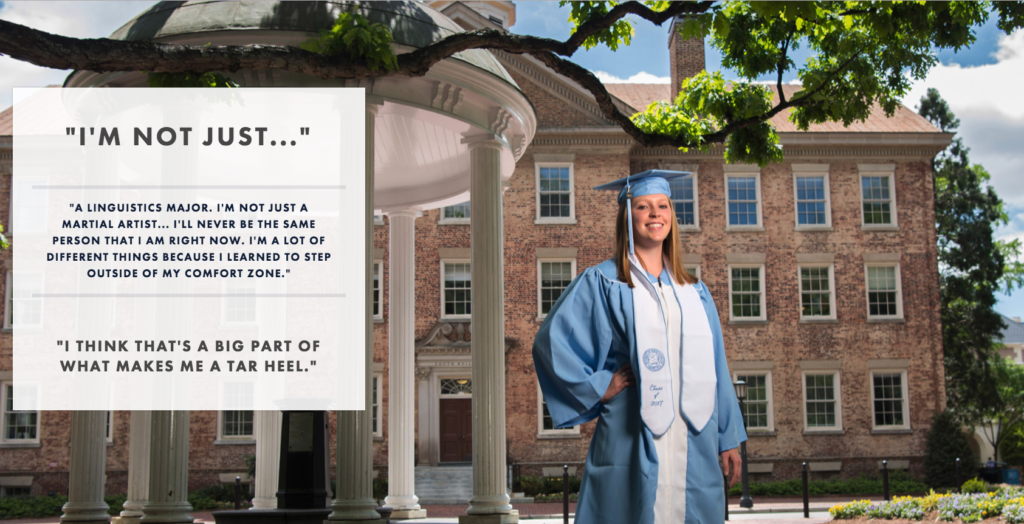

“We also found strong skin color gradients in respect to other aspects of life,” said co-author Krista Perreira, a professor of public policy in the College of Arts and Sciences, a fellow of the Carolina Population Center and associate dean for undergraduate research. “Those with darker skin color tended to have fewer years of education, lower levels of wealth and to experience more discrimination on the basis of their skin color.”

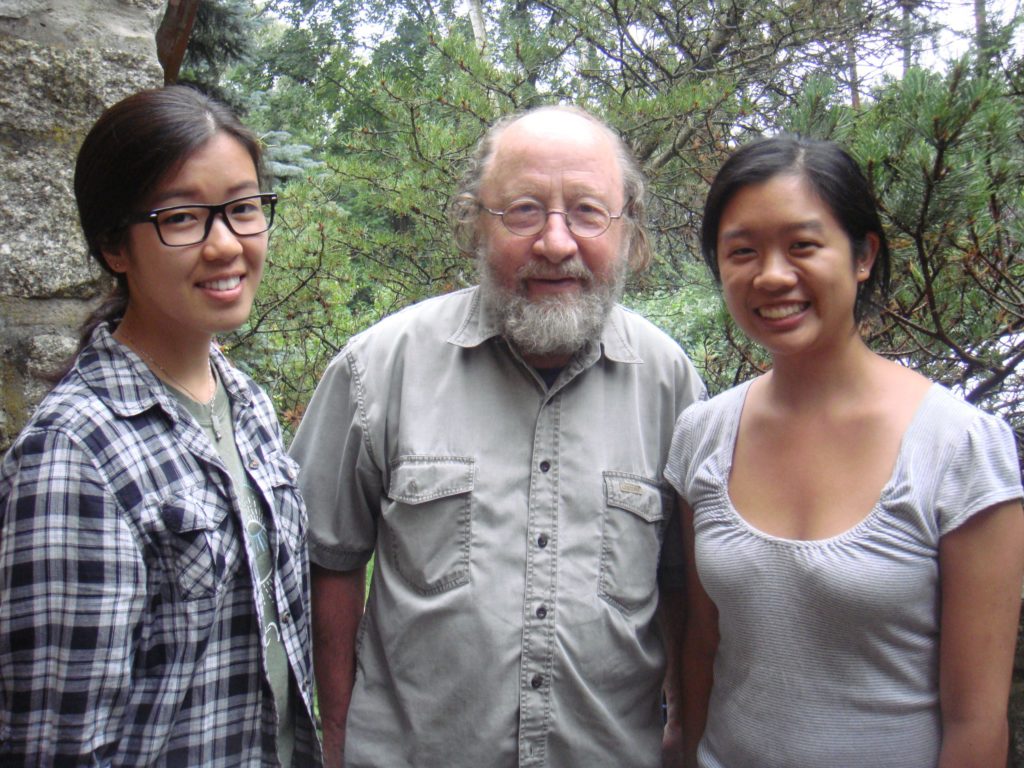

The study, conducted with Edward Telles, professor of sociology at Princeton University, appears online in Social Science and Medicine.

Latin America is one of the most ethnically and racially heterogeneous regions in the world. Despite that, few scholars have conducted studies that have focused on the relationship between ethnoracial identification and health disparities, Perreira said.

Researchers collected data on 4,921 adults in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. (The four countries have a combined population of about 392 million people or two-thirds of the population of Latin America).

They asked individuals to assess their health based on the following question, “Do you think your health is very good, good, fair, bad or very bad?” This self-rated health measure is a common tool used in survey-based data analysis and is strongly associated with an individual’s morbidity and mortality, Perreira said.

Other key findings of the study include:

- The odds of reporting good-very good health decreased significantly among individuals who reported discrimination on the basis of their incomes or educational backgrounds.

- The negative influence of poverty on health was greater in urban areas than rural areas.

- The positive association of education with good-very good health was strongest among respondents with lighter skin tones.

The results from Latin America are consistent with previous research that shows darker-skinned individuals report poorer physical, mental and infant health outcomes in the United States and Canada.

Future research could focus on more specific health problems such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease, Perreira said.

“As income inequality has grown and health reform pressure has mounted in Latin America, it has become increasingly important to understand how race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status shape health,” she added.

The study was funded in part by the Ford Foundation.