Kevin Currin remembers the fun he had when he attended Maze Day as a participant when he was in middle school.

Currin never forgot Gary Bishop, the computer science professor who came up with the idea of a special day of fun on campus for visually impaired children and had his students develop sound-based computer games for them to play.

Now a student at Carolina pursuing a career in computational biology, Currin was again on hand for the 10th annual Maze Day – not as a participant – but as one of Bishop’s students who designed a maze.

One of the first classes Currin took at Carolina was Bishop’s “Introduction to Scientific Programming.” He did so well in the class that he joined the growing legion of students past and present who each year turn Sitterson Hall into a virtual carnival for more than 100 visually impaired and blind children from across the state.

“Kevin has a station next to his laptop with his computer game where he will talk to these guys about going to college,” Bishop said. “The laptop he is using is horribly broken. It looks like something you would see in ‘The Matrix’ – with a screen blinking freakishly.”

Currin explained: “I closed my screen on my headphones once and you can see the headphone splotches there.”

Or so he has been told.

Bishop also gave Currin a special assignment: to talk to the kids who come to play his game about how they, too, could go to college.

The idea for Maze Day was spawned in 2001 when Bishop met Jason Morris, a blind graduate student in classics who told him about the Ancient World Mapping Center in Davis Library and how people there wanted to figure out a way to produce maps for the visually impaired.

“I put five of my undergraduate students on doing that,” Bishop said. Using a system called BATS (Blind Audio Tactile Mapping System), the students developed a map of Britain under Roman rule that Morris became the first to use.

“Afterward, they told me, ‘This was the first thing I did in college that mattered,’” Bishop said. And that was the professor’s eureka moment, when he realized that he and his students could become “geeks for good.”

Through Morris, Bishop met Diane Brauner, a certified orientation and mobility specialist, who told him about blind children in elementary school being left behind when the class went to computer labs because there was no software that made the computers accessible to them. And together, they hatched the idea of Maze Day.

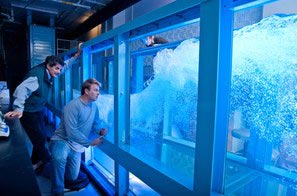

That first year, 2005, Bishop developed a game he called Hark the Sound, a collection of sound-based computer games that allowed visually impaired children to identify songs and animal sounds. Using cardboard, students also developed an actual maze for students to navigate, a practice that has continued every year since.

Two children who participated that first year – 10th-grader Bobby Ryals and 9th-grader Brooklyn Geise – have attended Maze Days faithfully ever since, except the year “the bus didn’t show up,” Ryals said.

“I definitely appreciate it,” he said. “You can tell with every game we play how much work they put into it.”

Geise said one of the things she likes about Maze Day is the friendships she has made with students over the years.

Both Ryals and Geise said they intend to go to college.

Maze Day was conceived as a day of fun for visually impaired kids, Bishop said, and while the games may have become more complex, that simple idea has stayed basically the same.

“I tell my students you can write a game that is more fun than nothing,” Bishop said. “OK, these kids have nothing. We can do something more for them than that.”

Like Ryals and Geise, many students come back year after year.

“We have teachers tell us that this is the first time I’ve seen this kid smile,” Bishop said. “They get to go on class field trips, but they are kind of the caboose. This is their field trip. So they come and have a good time.”

As Ryals explained, “It’s a lot better than going to the zoo.”

Story by Gary Moss, University Gazette; video by Beth Lawrence ’12