A recent U.S. Geological Survey report confirmed that the nation’s amphibians, including frogs, toads and salamanders, are disappearing “at an alarming and rapid rate.” A UNC biologist has found that North Carolina’s Southern Cricket Frog populations mirror this disturbing national trend.

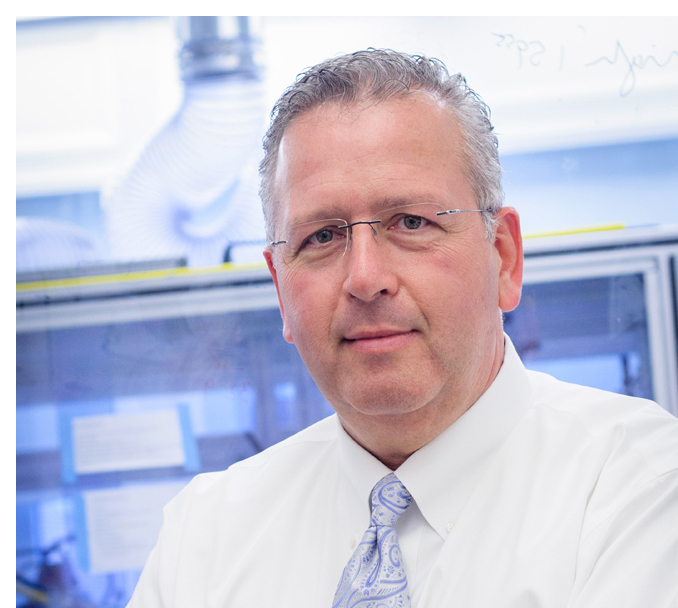

“It’s a steady flow of bad news for amphibians,” said Jonathan Perry Micancin [mih-CAN-sin], a visiting lecturer and recent Ph.D. graduate in UNC’s Biology Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. The cold-blooded animals require wetlands to breed and surrounding forests for food and shelter. They play an important role in nature’s food chain, Micancin said, eating insects and providing food for larger animals, including snakes and birds.

For his dissertation and ongoing research, Micancin studied two different but co-occurring species in North Carolina, the Northern Cricket Frog (Acris crepitans) and the Southern Cricket Frog (Acris gryllus). The northern species occupies the Piedmont as far west as the Appalachian foothills, while the southern species is found in the state’s Coastal Plain, between the Piedmont and the coast. The two overlap, a condition biologists call “sympatry,” in the upper Coastal Plain.

Micancin and his students searched for the tiny frogs – they are no more than 1 ¼ inches long – in wetlands throughout most of the state, from Crowders Mountain, near Charlotte, to Carolina Beach, south of Wilmington, to Merchants Millpond, in Gates County, and Lake Waccamaw in Columbus County. He used their distinctive calls as identifiers.

“The two species are hard to identify visually because they are so small and well-camouflaged.” said Micancin. “Fortunately, their calls are very different: Southern Cricket Frogs ‘chirp’ and Northern Cricket Frogs ‘rattle.’ ” Using statistical analysis, he confirmed that it is “easier to identify them by sound than by sight.”

Micancin and colleagues looked at specimens collected in the 1960s and housed in the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences, then compared those to field data they collected over several summers. While the Northern Cricket Frog remains in many places, the Southern Cricket Frog has disappeared from the upper Coastal Plain between the Chowan River and the Cape Fear River.

“We don’t know yet why this is happening, but we can expect that it does not bode well for amphibians and other animals that share their habitats, including humans,” Micancin said.

It may be that the Northern Cricket Frog is “bullying out the Southern Cricket Frogs,” which are slightly smaller, but human activity may also play an important role, he said. For example, the Southern Cricket Frog may be more sensitive to development than the Northern Cricket Frog. Climate change also could be affecting both species, which aren’t able to survive droughts or winter temperature fluctuations as well as other frogs, he added.

Micancin, whose family has lived for generations in northeastern North Carolina, pointed to significant changes to the Great Dismal Swamp and other natural habitats in the state.

“Over recent decades, as the state has grown, we’ve seen more roads and parking lots, rural residential developments, larger farms and clear-cutting of pinelands,” he said, all of which are affecting the habitats of cricket frogs and other amphibians, especially in northeastern counties.

Yet through his family’s heritage, Micancin is keenly aware of the high poverty and unemployment rates there, and the critical need for more economic opportunities – which usually means more development.

“It’s a balancing act, and we need more research to understand how to preserve habitats for hunting, fishing and conservation while providing for the economic needs of North Carolinians. I’m hopeful but realistic about how successful we will be.” he added.

Listen to the cricket frogs.