The best novelists seem to will their stories into creation, as if they fully formed the plot and characters in their minds and then merely put their ideas to paper when the spirit moved them.

Nonsense. Writers aren’t seers. They’re ditch diggers. They fret over word choice, sentence style, story structure, tone, pace, plot twists, character development. It’s a laborious process, producing a book, that only the great ones can make look easy. The hard truth is that some of the best writers don’t even know what sentence will come after the one they’re currently conjuring.

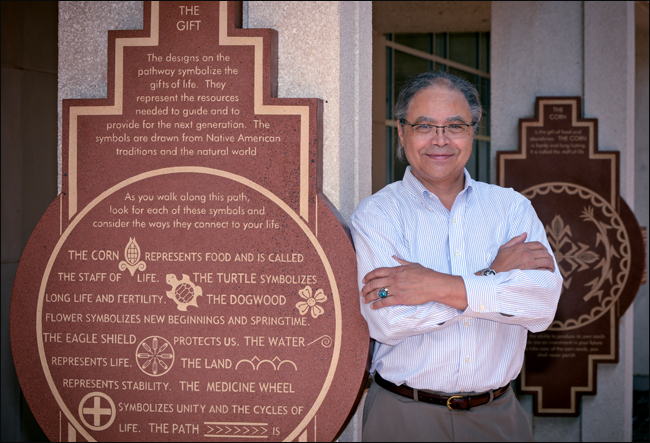

This brings us to the mind of Daniel Wallace, UNC professor and author of five novels, including Big Fish, which director Tim Burton made into a movie in 2003.

When I interviewed Wallace for an Endeavors profile back in 2008, he told me why Big Fish ended up feeling different than most novels. Some chapters are just a page long; others feel very independent. That’s because Wallace was taking care of his one-year-old son and could only find time to write when Henry was napping. The myths of Big Fish started off as standalone tales. Only after Wallace wrote them could he see how they might coalesce into a novel of mythic proportions.

But now Henry is grown up. Wallace, who has four more novels under his belt, finds more time to write these days, though he still approaches his craft in much the same way he did in the 1990s. And that’s one sentence at a time.

In the case of his latest novel, The Kings and Queens of Roam, it all started—as these things do—with a sentence that he wrote many years ago:

In the case of his latest novel, The Kings and Queens of Roam, it all started—as these things do—with a sentence that he wrote many years ago:

“Rachel McCallister and her sister, Helen, lived together in the home they grew up in, and as far as anyone could tell (Rachel and Helen included), this is where they would die as well.”

That’s all Wallace had. “All I knew is that somewhere out there another sentence was waiting to come after it, and after I wrote that second one, the third, the fourth, the fifth.”

As the sentences came, so did the story. Booklist describes it as “an eerie fairy tale for grown-ups … a melancholy yet enchanting pastiche of love, loss, redemption, and revenge.” And as Kirkus Review says, “A tale of love, magic and reconciliation … a fanciful story layered in symbolism and ripe with lyrical language.”

That fanciful-fairy-tale bit is vintage Wallace. I wouldn’t call it his shtick, but he’s become known for spinning fantastical yarns, and The Kings and Queens of Roam is no different. In a way, though, he simply takes what all novelists do to a stranger level.

“I think that every novelist strives to create a world all its own, something self-sustaining, an idiomatic ecosystem—a world brand-new and dangerous that feels, at the same time, familiar, warm, hospitable, a place a reader might want to hang out for a while,” Wallace says. “Doing both, that’s the big trick. This is why, to the degree I succeeded doing it, I think of Roam as my first novel. It’s a place you’ve never been to before, and neither have I.”

And yet, Wallace writes it as the all-knowing narrator with a style all his own, and that makes the journey through Roam all the more entertaining.

Daniel Wallace is the J. Ross MacDonald Distinguished Professor of English in the College of Arts and Sciences.

[Story by Mark Derewicz, Endeavors magazine]