With each breath, we inhale life-sustaining, oxygen-rich air. But that same air is also riddled with germs that threaten our health. Now, in collaboration between the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Medicine, scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reveal evolution’s design for keeping our lungs clean and healthy. The discovery, to be published August 24 in Science, not only revamps previously held beliefs on how the human airway functions, but also provides a unifying theory for how to treat seemingly different airway diseases, ranging from cystic fibrosis to asthma.

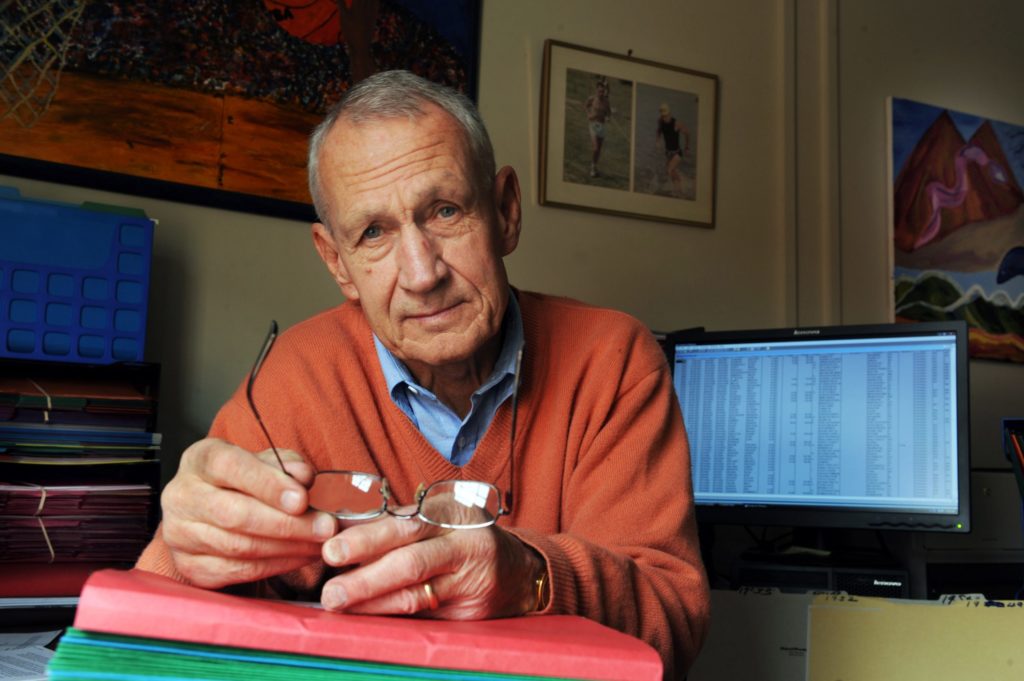

“The air we breathe isn’t exactly clean, and we take in many dangerous elements every minute,” said Michael Rubinstein, UNC’s John P. Barker Distinguished Professor of chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences. “We need a mechanism to remove all the junk we breathe in, and the way that is done is with a very sticky substance called mucus, which lines the airways and catches these particles before they reach the epithelial cells in the lungs. Hair-like extensions of epithelial cells called cilia then propel the mucus out of our airways and get rid of these dangerous particles.”

But if mucus is so sticky, why doesn’t it stick to the cilia that get rid of it?

Until now, researchers believed that the answer was water, which bathed the cilia and shielded them from the mucus. However, the researchers, including first author Brian Button, M.D., of the Cystic Fibrosis Research and Treatment Center in the UNC School of Medicine, now show that the water model is fundamentally wrong.

Instead, a mesh of molecules is tethered to each hair-like cilium resembling a brush; and as each cilium sways back and forth, the brush collectively propels the mucus forward. This brush-like layer keeps the sticky mucus from reaching the cell membrane, ensuring the normal flow of mucus out of the airways.

But in some lung diseases, like cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the brush becomes compressed and actually impairs the normal beating of cilia and healthy flow of mucus. Rubinstein said that whenever the mucus layer gets too dense, it can crash through the brush and stick to cells. “The collapse of this brush is what can lead to immobile mucus and resulting infection, inflammation, and eventually severe disease,” he said

The discovery could guide researchers to develop novel therapeutic strategies to treat chronic lung disease, such as by using drugs to make the mucus less sticky. Rubinstein and colleagues next plan to design ways to keep the mucus concentration at the necessary level. Their hope is to use these new findings to develop new treatments for a variety of respiratory ailments.