Susan Harbage Page has long held a fascination with borders and identity. For almost a decade, she walked the U.S.-Mexico border in the Rio Grande Valley, photographing and collecting objects that border-crossers left behind: A wallet. A woman’s hairbrush. A bra. A Bible. A tiny pink Croc. An eye shadow compact. The objects told her powerful stories about hope and heartache, borders and belonging, and sometimes, a great deal of violence. And they implored her to bear witness.

In 1969, when she was 10 years old, Susan Harbage Page went on a road trip across Europe with her mother and three sisters in a red Volkswagen van. It was a pivotal event in Page’s memory; they crossed about 22 borders in three months. She recalled listening to the moon landing when they were in Switzerland and getting lost on a country road in Turkey with military vehicles as their only road companions.

With the opening of travel to Eastern Bloc countries, they visited Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria. Then they crossed the border into Romania and everything changed.

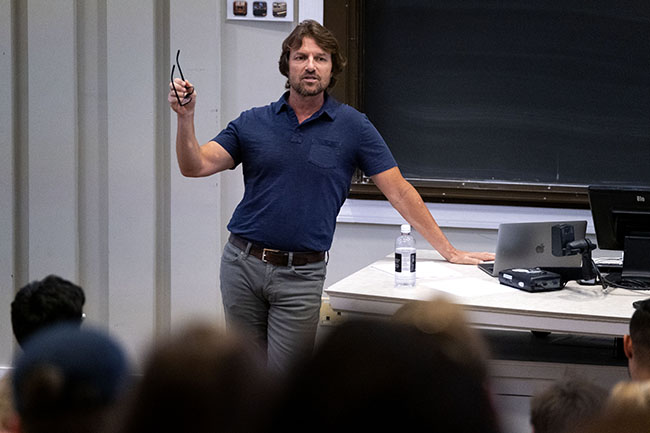

“We were held and detained for the better part of a day,” said Page, an artist and associate professor of women’s and gender studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. “They went through everything in our van. The border guards took all of our clothing and belongings and inspected them and sprayed water underneath the van. We were locked in a room, and remember, this was before cell phones. So there’s this idea of me, this privileged person, traveling with a first-world passport, but all of a sudden this passport no longer works. We were caught between two borders and belonged to neither one.”

It was just one of many events that would prove meaningful to her own border awakening. In 1996, she received a North Carolina Arts Council fellowship for a residency in Israel and Palestine, where once again she was interrogated at the border. She spent time in the Negev Desert with indigenous Bedouins who didn’t have access to water or schools. In 2000, she taught English as a second language classes to adult learners in Durham, where she learned about her students’ long and complicated journeys to the United States and the myriad places they called home — not just Mexico, but El Salvador and Honduras and Guatemala.

In 2007, she heard a story on National Public Radio about how 20% more women and children than men die crossing the U.S-Mexico border. She decided she had to see it for herself.

“I couldn’t get it out of my head, so I just bought a plane ticket to Texas. Now, I think about some of the things I did at that time,” Page said, chuckling. “I remember I rented a red car, and I drove all along the border. I bought one of those now old-fashioned books with pages of detailed maps of the border area in the Rio Grande Valley. I was using my old Hasselblad film camera. I started seeing the things people left behind. I knew they told an important history, so I started picking them up.”

It was a journey she would make at least once a year for eight more years. To Brownsville, McAllen, Progreso, Laredo. She was intimidated by Border Patrol and Army officers and chased by helicopters.

During that time, she collected more than 1,000 objects, took about 30,000 photographs and interviewed border-crossers, immigration lawyers, Border Patrol officers, government officials and others.

Everyday objects and the anti-archive

When Page was asked what made these artifacts — cell phones, underwear, toothbrushes, eyeglasses, deflated inner tubes, shoes — so compelling, she said simply: “That’s just it. They are everyday objects, abandoned in this space in between two nations, cast aside either through necessity or force.”

They are also much more, she added. “They are portraits of individuals.” They reminded her of icons she had seen in Italy as a child, such as cloth swatches believed to be from the robes of Saint Francis or the bones of Santa Chiara.

The objects themselves take on different identities. Toothbrushes are used for hygiene but also seen by Border Patrol officers as sharp objects and potential weapons. A woman’s bra usually means she has been raped, and a coyote or human smuggler has left it behind as a sign. Sometimes the objects have been altered; Page has a pair of pants that has been hemmed by hand, a shirt that is carefully folded and a comb with someone’s initials scratched onto it.

One of the most meaningful objects in her collection is Alex’s wallet.

“The wallet belonged to Alex Ramirez Cuba who was 18 and traveling from Honduras, and when I found it, my own son was 18,” she said. “It was all wet and was on the U.S. side of the river, right by the bank. All of the contents were thrown out in the dirt. There were a few pesos, his birth certificate, his passport and two little pieces of notebook paper with blue lines and phone numbers on them.”

Page was thinking early on about what it meant to document in this border space. She decided not to sensationalize or criminalize migrants’ stories by photographing them at their most vulnerable. If she saw someone, she put her camera down. She would let the objects tell their own stories of courage, fear and hope.

“I also learned to read the landscape and the archaeology of pathways, “she said. “Getting in a canoe is mind-blowing because you can look on both sides of the river for miles and miles. You are literally on the border. You can see pathways coming in from the south bank of the river and a corresponding path out on the north bank. It is a perspective most will never see, an imaginary space for most Americans.”

Page documented objects where she found them, but she also collected them, mud and all, and took them back home for what she calls “The Anti-Archive of Trauma on the U.S.-Mexico Border.” She photographed and tagged them with an accession number in her studio, using bright colors as a background instead of stark black and white because she did not want to imply that the objects were evidence of a crime.

Her work has been exhibited at major museums and public institutions across the United States and around the world, most recently this past summer at the Gregg Museum of Art and Design at NC State University, which showcased both her photographs and her archive of objects.

She’s also created about 15 site-specific projects and interventions along the border, like a floating bridge made of inner tubes between the U.S. and Mexico border called “Crossing Over,” created with artists from both countries. In a performance piece, she stopped traffic in the middle of the Progreso International Bridge by climbing over a cement security barrier and laying on the ground.

“Some of that was me trying to come to terms with, ‘What is a border and do I have a right to be here?’ My work has always been about trying to figure things out and to make other people see and pay attention,” Page said. “I don’t have all the answers, but I want to create a dialogue.”

Textiles and teaching

If Page is enthusiastic about her research, she’s equally as animated about weaving her work into the classroom. She has been a champion of using BeAM makerspaces in her courses and served on a new faculty orientation panel about infusing research into teaching.

Since 2013, she has taught “Art and Social Change: Borderlands and Story in Contemporary Visual Art.” Her students used BeAM for their final projects, which highlighted the borders and boundaries in their community at UNC.

This semester she is co-teaching a new Ideas, Information and Inquiry course, “Experiencing Latin America: Bodies, Nature, Belonging,” with Gabriela Valdivia in geography and Gosia Lee in romance studies. A requirement in the new IDEAs in Action curriculum, Triple I courses are team-taught by faculty members across three disciplines and encourage interdisciplinary thinking. The class is examining migration, justice and environmental well-being through Spanish language-based films and artwork to foster a global understanding of identity and belonging in the Americas. It is taught in English and Spanish.

On a recent Tuesday morning, Lee opened the class in Spanish as students learned about Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara. Then Page introduced another art form she is passionate about: textiles. Students were given embroidery kits and taught how to make basic stitches on a piece of muslin.

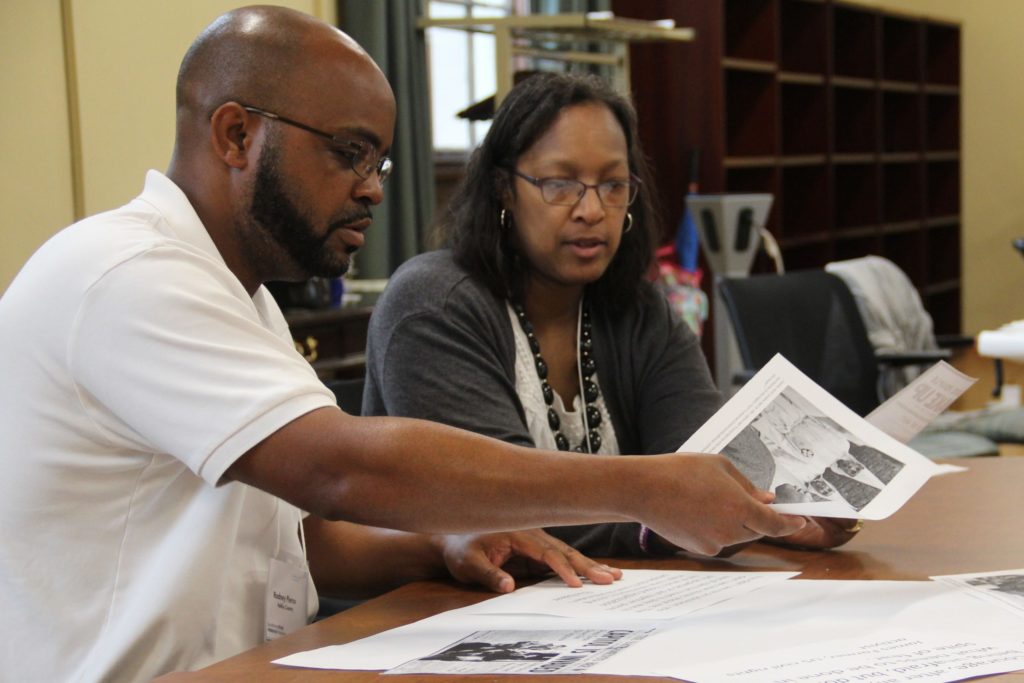

A week later, students expanded on their initial sewing lesson and presented their “Cartography of Resistance” projects in an informal classroom exhibition, spreading their artwork across chairs, taping them to walls and scattering them on tables and desks.

They illustrated what “bodies, nature and belonging” meant to them in creations stitched onto squares of cloth, a bookbag, a shoe, a T-shirt, a dress, a spiral-bound notebook, a pillow, a glove and other objects.

“These are amazing. You did such a good job of learning the technique and visually expressing your ideas,” Page told the students. “Now let’s unpack this a little bit as a group: What surprised you about this project?”

For years Page has been interested in the intersection of women, textiles and labor. She once worked in a Charlotte textile factory and for a long time has collected bits and pieces of handmade lace and embroidery. In 1992, she received a Fulbright Travel Grant and made the first of many annual trips to Spello, Italy, where she photographed secular and sacred objects. During that journey, she met a group of Augustinian nuns and lived alongside them in their convent as she began to document their embroidery and lace-making, their only means to earn money. She also created a new way of looking at their work — examining and altering the designs of old pieces of lace and graphically retracing them, stitch by stitch, on translucent paper. An exhibition of her drawings, “History’s Pull, Conversations with Lace,” was held in Rome, Italy, in 2013.

Page’s art, through her textiles and photography, has always been about opening her own eyes as well as others to the world around them. She shared a quote by artist Ann Hamilton, whom she admires: “Pay attention to the things your eyes want to look at.”

Her work is both timeless, and with the current political situation at the border, more timely than ever before.

In the Gregg Museum catalogue, Page explained that she chose to walk the border simply because she could. Often it wasn’t her passport or driver’s license but rather her faculty credentials that granted her privilege and access. And with that access, she believes, comes responsibility.

“Only my intent to be present and help map the violence and trauma of this liminal border space provided the strength to witness a story of identities shed in search of safety and the human belonging to belong,” she wrote.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Page recently returned to the U.S.-Mexico Border with Myers Park United Methodist Church in Charlotte where she gave a talk about her work. The team visited asylum seekers in the refugee camp in Matamoros, Mexico, and passed out more than 1,000 meals. Read more on her blog.

Listen to an interview with her on “The State of Things.”

UNC-Chapel Hill celebrates University Research Week Nov. 4-8.

By Kim Weaver Spurr