Associate professor Andrew Mann is building small satellites in campus makerspaces to discover young planets that could one day sustain life.

When Andrew Mann interviewed for his job as an astronomy professor at UNC-Chapel Hill a year ago, he told the hiring committee he wanted to buy a satellite to send on space missions.

“No, no, no,” they told him. “Don’t buy one. Build one.”

It was an intriguing idea. A satellite for a large-scale mission can easily cost $200 million to buy and launch. Instead, the department promised a team of University-based physicists, astronomers and engineers who could support Mann in building his own miniature satellites on campus, all for less than $10,000.

“They were really excited about the whole thing, and that kept me interested,” said Mann, an assistant professor in the College of Arts & Sciences’ physics and astronomy department. “But I’ve never built things made for space before, and I was sort of like, ‘What do I need? What do I do?’”

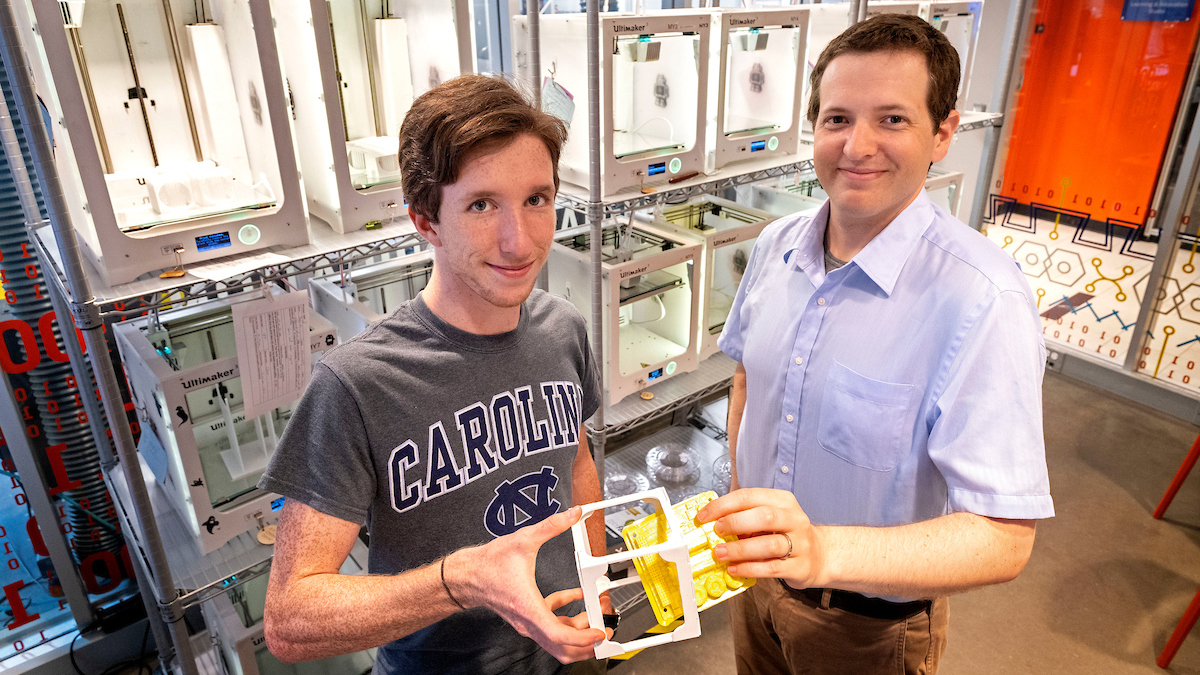

Mann’s colleagues jumped in to help, and rising senior Patrick Gorman volunteered his engineering prowess to create a prototype of a small satellite called a CubeSat.

“We’ve been using the 3D printers in the makerspaces to pull out prototypes of what we want to build,” said Gorman, a biomedical engineering and astronomy student who leads a campus organization called UNC Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. “It’s been an awesome on-campus resource for us.”

CubeSats, which Gorman calls “the next big space thing,” are hardly bigger than a Rubik’s cube at their smallest and weigh less than three pounds, making them relatively inexpensive to produce. Although they aren’t as advanced as other, pricier research spacecraft, Mann said they have the potential to be nearly as good.

“They’re basically amateur-sized telescopes in space,” he said, adding that CubeSats can measure the size of nearby planets and collect other important data by sensing light patterns. “We’re not going to build Hubble — that costs millions — but we can do something small, and it can do lots of things that Hubble can do.”

Mann believes the CubeSats will help him discover young planets that have the potential to become habitable. He calls them “proto-Earths” — planets that are about the right size and have the characteristics to potentially sustain life one day.

“We don’t know exactly what the conditions for life are, but let’s just assume it has to be a clone of earth,” Mann said. “You can think about it as a giant checklist. It needs an atmosphere, and we know what kind of atmosphere was required to build early forms of life on earth. Then we look at whether it’s in the right orbit to have water. If it’s too close to the star, water will be evaporated. If it’s too far, water will be ice. And you keep working through the list.”

The Carolina CubeSats will help Mann answer a few of his most pressing questions: what conditions give rise to Earth-like planets, how many of them exist today, and how many might become habitable one day? The answers will give scientists an unprecedented glimpse into the origins and evolution of planets, as well as the precursors to extraterrestrial life.

So far, researchers have identified three young, Earth-sized planets, but Mann hopes to use his satellites to discover as many as 30 over the next several years. For now, the team is working hard to make their CubeSats “space-worthy,” which Gorman said means equipping them with the same level of durability required of surgical implants like titanium femurs.

“It’s a very involved process, so it gives me a lot of experience in electronics, design, building, and radio,” said Gorman, who is also developing the computing system that will communicate with the CubeSats in space. “Dr. Mann and I are both super enthusiastic about all that we’re trying to accomplish.”

Mann, who spent his youth hanging out with the high school astronomy club and scraping together enough money to buy the school a telescope, is just as excited to share his bold vision with Carolina students as he is to send the satellites into orbit. He plans to launch his first CubeSat within the next two to three years.

“When we launch it, it’s going to be a big deal,” he said. “Part of my dream is having a great group of students at a launch pad, watching it go up. That’s part of the vision. That would be really, really great.”

By Emilie Poplett, University Communications