From the shores of New Jersey to the North Carolina coast, Pete Peterson has always loved the ocean. He’s spent nearly five decades researching its marine life, fighting for its protection, and guiding the next generation of marine scientists to do the same.

Just past midnight on March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez strikes Bligh Reef in Alaska’s Prince William Sound. Sharp rocks tear through the ship’s steel hull, and an onyx torrent explodes into the sound. By sunrise, oil blacks out the surface of the water and continues to spread — quickly. Just two days later, almost 11 million gallons of oil has swept across 1,200 miles of coastline, killing hundreds of thousands of fish, marine mammals, and seabirds.

At that point, the Exxon Valdez oil spill was the largest to occur in American waters — only surpassed in the last decade by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico — and is still considered one of the most devastating human-caused environmental disasters. While 30 years have passed since the event, there are still approximately 16,000 to 21,000 gallons of oil on the beaches of Prince William Sound. Five years ago, the sea otter population finally returned to its pre-spill numbers, but extinction threatens one of just two remaining pods of orcas in the area.

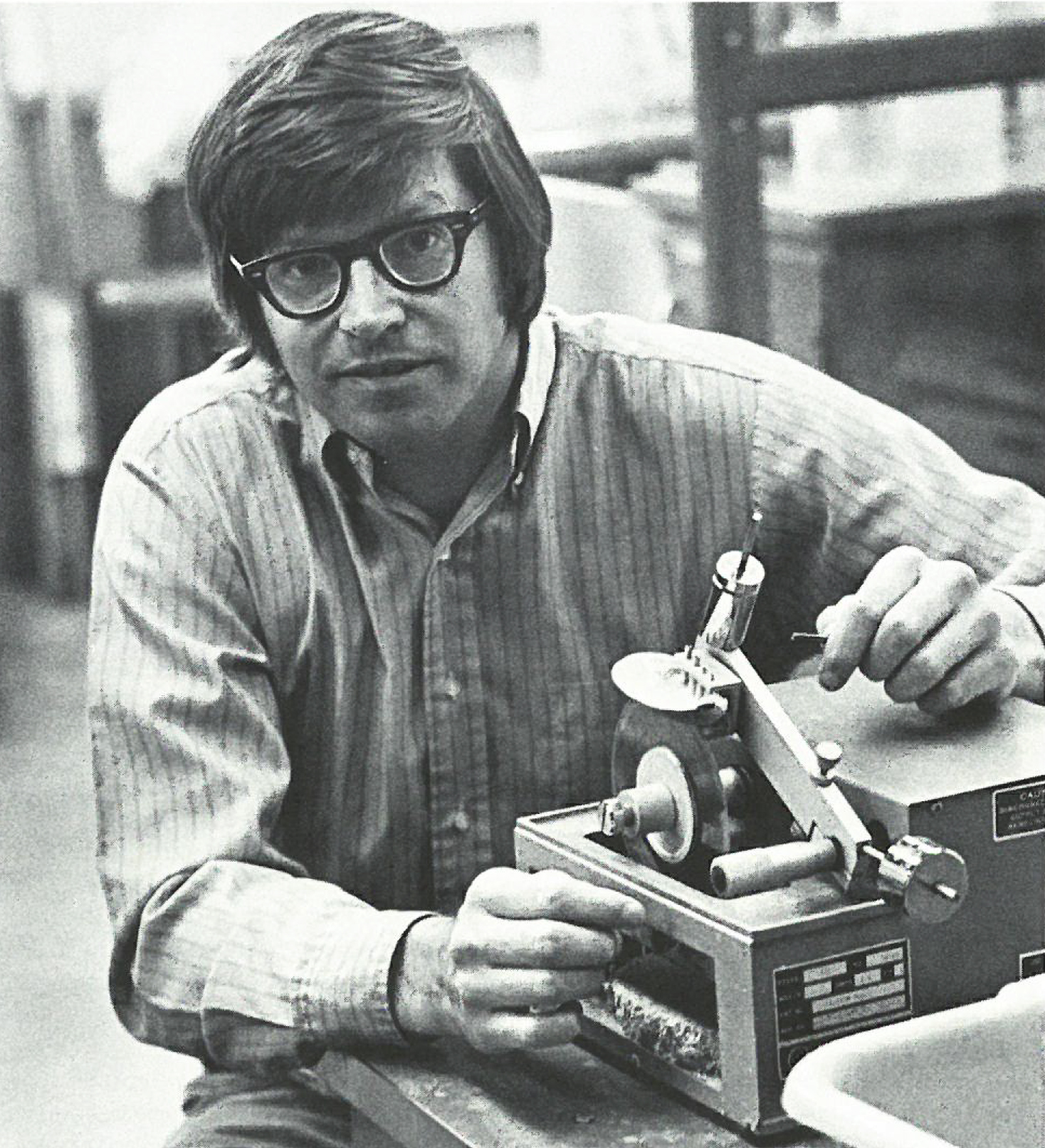

Charles “Pete” Peterson, a researcher with UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS), was on the front line of assessing the ecological repercussions of the spill. Between 1993 and 2014, he advised the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council and its executive director on the effectiveness of restoration efforts and reviewed long-term research proposals.

But Peterson is not a one-track scientist. He looks at the big picture — an approach that, during the Exxon Valdez crisis, wasn’t something many scientists acknowledged.

After countless hours analyzing scientific papers and studies, Peterson wrote in the peer-reviewed journal Science about the unprecedented scope of the Exxon Valdez spill and the steps to take going forward. In the article, he advocated for the revolution of ecological risk assessments in the wake of oil spills. He argued that such disasters — including the Exxon Valdez spill — have long-lasting and ecosystem-wide repercussions and that scientists could not continue to focus on individual species or systems like they had been.

“The response needed to look at all of the pieces of the puzzle,” Peterson says.

Peterson contended that scientists needed to look at how different parts of the ecosystem were connected. The article was cited more than 1,000 times, and his research was critical in developing a new understanding of oil spills.

Aside from a pioneer in oil spill ecology, Peterson is an alumni distinguished professor with IMS and an internationally acclaimed conservation ecologist. He is a passionate defender of marine and coastal ecosystems and has built a legacy of engaging with ecological problems through new and interdisciplinary angles.

While his title is first and foremost scientist, Peterson is also a writer, mentor, and spearhead for science policy. Before it was conventional, he recognized the importance of sharing his research with decision-makers and his community.

And on June 30, after 47 years of service to science, he retired from the university.

“We oftentimes have this view of scientists being in their ivory tower,” one of his recent PhD students, Avery Paxton, says. “He definitely feels that it’s his obligation to communicate the results of the science back to the policy makers and the general public. And I think that’s something we can all aspire to.”

Shells and surf

As a young child, Peterson spent his summers on a narrow barrier island near New Jersey’s Island Beach State Park. It was there, wandering along the seaside, that he first became acquainted with coastal science.

“I was intrigued by seashells,” he says. “I’d collect them on my long, otherwise boring walks on the beach.”

At just 5 years old, he was full of questions. Where did the shells come from? How were they made? What were they called?

“I bugged my folks until they got some books on how to know your shells,” he laughs.

His interest in shells evolved into a passion for science. While in high school, Peterson received an award from the National Science Foundation to spend a summer studying coastal systems at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California.

During his first week there, he’d walk to the beach and surf during lunch breaks. “The waves were just terrific,” he says. “I went out and rode waves, and I looked over next to me and there was my advisor for the lab. He was an absolutely world-famous chemical ecologist. And here I am thinking, oh gosh — you don’t have to give up surfing for this career! That’s the place I need to go.”

Peterson went on to earn an undergraduate degree in biology from Princeton in 1968 and then a master’s degree, PhD, and postdoctoral degree in zoology from the University of California Santa Barbara. There he studied under some of America’s ecology greats: his graduate advisor was Joseph Hurd Connell, an influential ecologist whose work greatly contributed to the scientific understanding of tropical rainforests, coral reefs, and biodiversity.

Peterson began teaching at Carolina in 1976, four years after completing his postdoctoral degree. Even then, his shell collection continued to act as a timeline of his life.

“I have shell collections from before I thought about a career in science, and shell collections from later on in various stages of my career,” he says. “They’re like jewels — jewels freely given by the sea. If you go out and collect the seashells, the bones of the invertebrates that make shells, you’re not really doing damage to the living populations. You’re celebrating them by finding the record that they left behind.”

Community communication

As he worked, Peterson noticed that many of his colleagues saw the publication of journal articles as the end of the line. But he wanted to look beyond that — and into how his research could change minds and policies.

“It’s important to make your message clear and translate that message. If you see a problem, there’s a problem. But solving that problem is no easy feat,” he says.

So Peterson committed himself to imbuing science with the real world. He has worked with teachers to formulate lesson plans, taught his students how to craft clear messages aimed toward the public, and worked with myriad organizations and committees. He is also deeply involved with his community in Morehead City and speaks with fishermen, scuba divers, and residents about the implications of his research.

“We’ve got to recognize that the message needs translation into the terminology, words, concepts, and images that are not scary to people,” he says. “You need to speak their language, put it in their terms. And if possible, apply it to real-world things going on in their backyards.”

Peterson argues that communicating science to the public is key to improving environmental policies. He has sat on over 20 scientific steering and advisory committees including the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission, the state’s major environmental policy-making body, from 1989 until 2013. He served as the chair of the commission’s Water Quality Committee for a number of years.

“We had a very broad area of expertise covered in that commission by people who are effective, well-involved, and engaged,” Peterson says. “I had really deep friendships and still do with professionals in our state government and environmental programs.”

In 2007, the Coastal Federation presented him with a Pelican Award for outstanding environmental service by a state government official.

His experience with oil spills has also made him a supporter of wind energy off the North Carolina coast. His research has helped expand knowledge and develop policies for coastal energy sources that move away from destructive offshore oil drilling.

“We did a ton with offshore wind energy when it was kind of new. We were the cutting edge,” Peterson says. “When Beverly Perdue was governor, we had a governor’s committee on energy. We had people with an interest in wave energy, an interest in offshore oil and gas, but in ways that could be more sensitive to the environment.”

Peterson has made a point in training his students to communicate their science clearly, too. And the most important thing he’s taught them?

“Strunk and White’s ‘Elements of Style,’” he smiles. “The little book of how to communicate and not sound like a scientist.”

Every step of the way

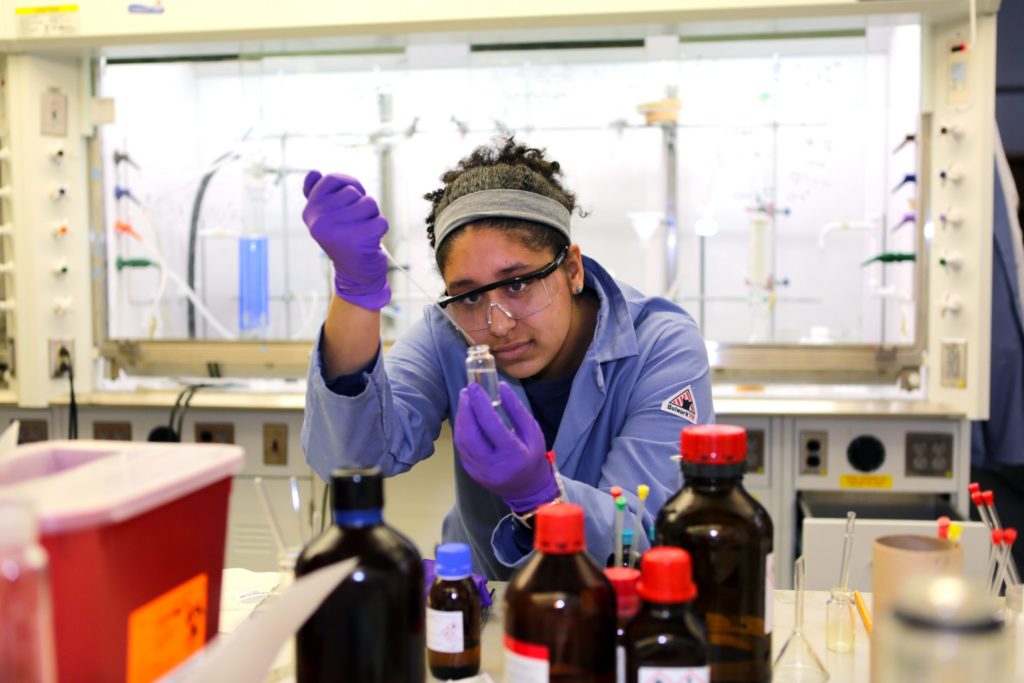

Out of everything that he has accomplished — the research, the awards, the committee chairmanships — Peterson says that his work with students is the most fulfilling. He has trained close to 50 PhD and master’s students and mentored hundreds of postdoctoral and undergraduate students.

“Students are what I treasure,” he says. “I am most proud of the training that I’ve done with graduate students and undergraduate students who will follow me and others. I have been particularly devoted to the support of women in science.”

One of these women is Avery Paxton, a former PhD student who Peterson advised while she chased her degree in biology. Paxton finished her program in May 2018 after six years of work.

Now a visiting scholar at the Duke University Marine Laboratory, Paxton studies sharks, artificial reefs, and the development of offshore energy. She owes a lot to Peterson, she says, and he is a trusted colleague and friend.

“Throughout my PhD program, he was my absolute biggest advocate. He was there for me every step of the way,” she says.

Paxton remembers struggling to write a funding proposal during her first summer in Morehead City. She had never written one before, and came to Peterson for help.

“Alright Avery,” he had said when she presented her dilemma. “Block off your whole day.”

The two of them sat in his office while he went over her grant proposal with a fine-tooth comb — it took almost eight hours. He helped fix minute errors in grammar and showed her how to word sentences and develop her ideas.

Now, Paxton is an active science communicator. As a member of the board of directors for the Scientific Research & Education Network, she connects scientists with K-12 educators. She is also a lead field researcher for the citizen science project Spot a Shark USA, which involves non-scientists in studies on sand tiger shark behavior and conservation efforts.

“You not only need to be a scientist,” she says, “but you need to be able to communicate your science and manage the lab and the funding to be successful. He really prepared us all for that.”

Years earlier, Peterson made a similar impression on Mary Watzin, now dean of North Carolina State University’s College of Natural Resources. She was one of Peterson’s PhD students in the early ’80s and, under his guidance, studied meiofauna, the tiny animals that live in aquatic sediments.

“He was a big thinker at the time. It was great working with him,” Watzin says.

Although Watzin’s research led her inland to wetlands and stream systems, the things she learned from Peterson stuck with her.

“The way that he taught me to think as a scientist came with me through all of that and was a really important part of my success,” she says.

Watzin remembers looking after Peterson’s dog, Caliban — named after the island-dwelling half-human, half-beast from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” — and spending long days with Peterson in Bogue Sound collecting data for his clam studies. Clad in a wetsuit, she would kneel on the muddy bottom with the other graduate students and pull up cages filled with clams to give to Peterson, who would then measure them.

“It was all hands on deck,” Watzin laughs. Those days were long and grueling, but she says that her work with Peterson helped shape her path and get her to where she is today.

“Best version of books on tape”

Michael Piehler, the director of UNC’s Institute for the Environment, says that Peterson is invaluable to IMS as a scholar who engages with the community. He admires Peterson for recognizing that research isn’t finished when the data is analyzed, but rather when that information is conveyed to people who make decisions.

Piehler, who became a faculty member at Carolina in 1998, met Peterson while completing his graduate degree at IMS.

“When I transitioned into a faculty role, he was a really important mentor to me,” Piehler says. “When you’re a junior faculty member, having someone looking out for you is a really positive thing. It can be a little overwhelming trying to start.”

Peterson pulled Piehler into projects and proposals and helped him find his balance as a researcher. They published eight papers together on topics such as coastal food webs, adaptive options for climate-sensitive ecosystems, and the economic value of oyster reefs.

Piehler fondly remembers a time in the early 2000s when Peterson invited him to a meeting that he had put together in Annapolis, Maryland, for scientists to discuss climate change and coastal systems.

The two of them jumped into a state-owned truck and took the scenic route north from Morehead City. Piehler drove and Peterson sat in the passenger seat, flipping through important climate papers as they whipped by farmland and pine forests. For at least half of the seven-hour drive, Peterson read the scientific papers aloud to Piehler, critiquing and analyzing them as he went.

“It was like the best version of books on tape that’s ever been,” Piehler says, chuckling. “I was really prepared when we got to the working group. I think of myself as a scholar, but he’s a scholar in a way that is eclipsed by few.”

An oyster’s value: not just the pearl

Peterson has published over 250 papers on topics ranging from fisheries management to coastal habitat restoration. More than 100 of his papers have been cited upward of 100 times by other scientists, a testament of the mark he’s made on coastal research.

A focus of Peterson’s research is oyster reef ecology. Oyster reefs are important habitats for marine organisms, which use their complex structures for hiding places and feed from the algae that grows on them. Oysters improve water quality by filtering out nutrients and protect coastlines from storms and floods by stabilizing and slowing wave energy.

Oysters are an important fishery in North Carolina — but over the last 100 years, populations in the state have declined by 50 to 90 percent due to overharvest, disease, and pollution. “This issue has significant statewide implications for tourism, environmental protection, and targeted economic development,” Peterson wrote in a 2015 article for the News & Observer.

To show the economic prosperity of oyster reefs, Peterson and his colleagues quantified the value of services such as habitat creation, shoreline stabilization, and pollution reduction. They found that the ecosystem benefits of oysters are worth $4,180 per acre.

“Oysters represent natural capital, returning dividends in the form of valuable services to the environment and to the people,” he wrote.

Peterson’s research has contributed to environmental regulations and management strategies to protect and restore oyster reefs. In April 2008, he helped rewrite coastal stormwater standards that would protect oysters and other sensitive coastal habitats from polluted runoff. He has since worked to improve those standards.

As Peterson enters his retirement, he will leave behind a legacy of interdisciplinary science. He has spent decades teaching, working toward policy change, and uncovering the riddles of the planet’s oceans and coastlines. But now, after 47 years as a scientist, he’s thinking about the next step. And that next step may be Florida’s gulf coast.

“I’d like to move down to Longboat Key,” he says. “It’s known for shell collecting.”

Charles “Pete” Peterson is the joint distinguished professor in the Department of Marine Sciences within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences and at the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences.

Avery Paxton is a postdoctoral fellow with the South-East Zoo Alliance for Reproduction & Conversation and a visiting scholar at the Duke University Marine Lab. She received her PhD in biology from UNC-Chapel Hill.

Mary Watzin is the dean of the College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University. She received her PhD in Marine Sciences from UNC-Chapel Hill.

Michael Piehler is the director of the UNC Institute for the Environment, professor in the Department of Marine Sciences within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences, and professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering within the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. He also holds a joint appointment at the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences.

By Annie McDarris, Endeavors magazine