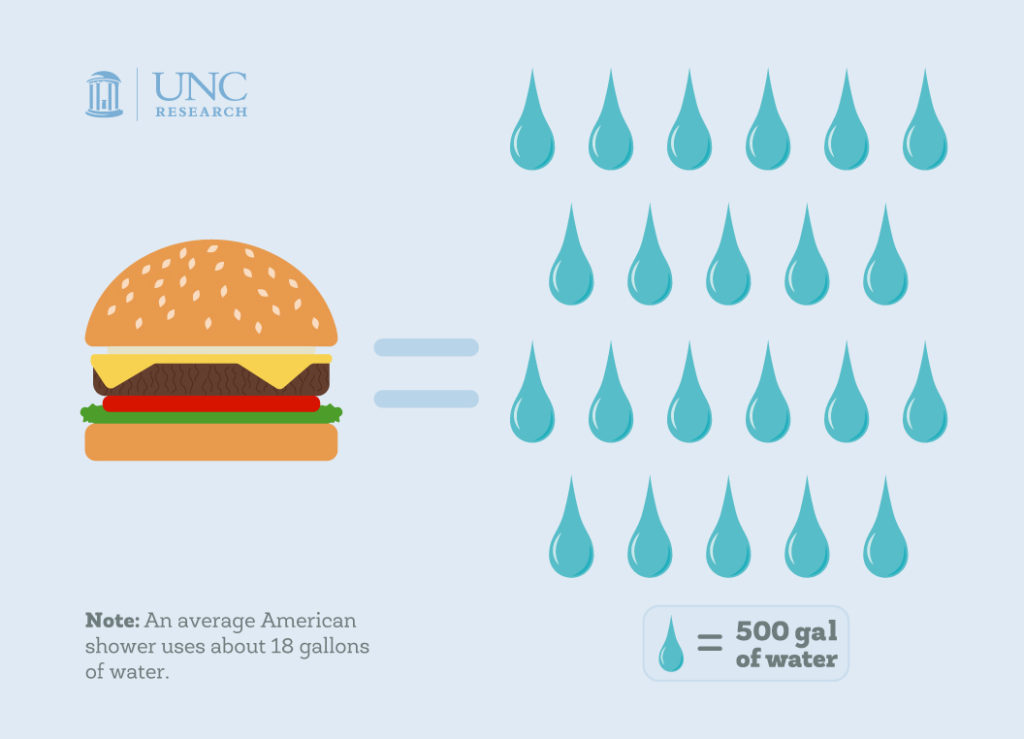

Eddie and Laura Taylor’s combined income is $37,800 a year. Their credit is so-so. When they applied for a mortgage loan, they were only able to make a down payment of 3 percent of the price of the house.

Borrowers like the Taylors (not their real names) can have a hard time getting a good loan because of their low income, their credit history, or a lack of money in the bank. Mortgage lenders make loans with the intent to sell them to financial services corporations such as Fannie Mae—but if the loans are considered too risky, corporations won’t buy.

Before the subprime-mortgage crisis, people like the Taylors might have gotten a loan—one with lots of fees, or adjustable rate that made their payments skyrocket after a couple of years or even months. Now, post-crisis, traditional lenders might not give people like the Taylors a loan at all.

There’s a middle ground: the 30-year, fixed-rate loan, says Roberto Quercia, who researches homeownership and lending at the Center for Community Capital.

Many low-income people still don’t have access to good fixed-rate loans because they don’t meet some of the traditional criteria for income or credit history that would make them prime (“safe”) borrowers. Race is also a factor, Quercia says. His research team studied mortgages in Atlanta, for example, and found that residents of black neighborhoods had more risky, high-cost mortgages, even after the team controlled for the fact that people in those neighborhoods also had lower median incomes and lower credit scores.

Since 1999, Quercia and others at the Center for Community Capital have been tracking how people with low incomes do when they get 30-year, fixed-rate mortgages from lenders who evaluate their applications carefully and don’t qualify them for more than they can handle. These loans come from around the country, and they’re sold to Self-Help, a community-investment lender in Durham, North Carolina. Self-Help pools the loans and retains the risk; then it sells the loans to Fannie Mae.

So far it’s been a good bet for Self-Help, says Quercia, who with two of his colleagues wrote a book, Regaining the Dream, about Self-Help’s Community Advantage Program and sound mortgage lending. Most of the program’s 46,000 borrowers have never missed a payment on their loans. If they do, their lenders contact them right away and refer them to a credit-counseling agency for a telephone counseling session. The borrowers usually accept this help and get back on track, Quercia says.

Over the ten years of the center’s study, the borrowers kept up with their payments almost as well as prime borrowers with fixed-rate mortgages do, and much better than prime borrowers with adjustable-rate mortgages. Most of the Community Advantage Program borrowers weathered the collapse of the housing market fine and are still paying off their loans.

The researchers decided to write Regaining the Dream in part because they were frustrated with rhetoric they heard in Washington, D.C., and on Wall Street blaming borrowers for the subprime-mortgage crisis, Quercia says. “After the crisis hit, the pendulum swung from making loans accessible in a way they shouldn’t have been to the other extreme, where lending now is very restrictive,” he says. “You really need to have an excellent credit score and ability to make a high down payment.”

Right now, policymakers and regulators are working out new standards for mortgage loans that may require lenders to keep some of the risk when they sell a loan, unless the borrower has put down a large down payment—perhaps 20 percent. “We know from our research that loans with smaller down payments are safe” when lenders match the size of the loan to the borrower’s ability to pay, Quercia says. “If we define a safe mortgage as having a high down payment, we’re likely to exclude from mainstream lending a lot of borrowers who are disproportionately low-income or minority.”

Right now, policymakers and regulators are working out new standards for mortgage loans that may require lenders to keep some of the risk when they sell a loan, unless the borrower has put down a large down payment—perhaps 20 percent. “We know from our research that loans with smaller down payments are safe” when lenders match the size of the loan to the borrower’s ability to pay, Quercia says. “If we define a safe mortgage as having a high down payment, we’re likely to exclude from mainstream lending a lot of borrowers who are disproportionately low-income or minority.”

Quercia and other researchers from the Center for Community Capital have presented their findings to the Federal Reserve Board, House of Representatives finance subcommittees, and other regulators. They promote the Community Advantage Program model: fixed-rate mortgages, well-researched loans, a supportive lender, and access to a secondary market to sell the loans.

That last piece was provided for the Community Advantage Program by a grant of $50 million from the Ford Foundation. Self-Help bought loans and resold them to Fannie Mae, while using the grant money as insurance that would cover the loans if they failed. Because the borrowers are doing well, Self-Help hasn’t lost money on the deal; it still has that $50 million, and it can keep buying more loans.

“In order to extend this program nationally, you’d need a fund like that that would create an insurance pool to allow loans to be sold in the secondary market,” Quercia says. Without saying exactly who should pay for how much of this fund, the researchers point out that every U.S. industry benefits from the stability of the housing market, and every industry suffered when the market collapsed—so insuring its future health is everyone’s problem.

Will the dream of homeownership start coming true for more minority and lower-income Americans? “I think so,” Quercia says, “because in the future the bulk of borrowers are going to be minority or low-income. By 2030, if not sooner, we’re going be a nation that’s majority minorities. So if I’m a financial institution, loans to these people are going to be my bread-and-butter lending. Necessity, I think, will make us learn how to do this correctly.”

Roberto G. Quercia is the director of the Center for Community Capital and a professor of city and regional planning in the College of Arts and Sciences. He co-authored Regaining the Dream: How to Renew the Promise of Homeownership for America’s Working Families with senior research associate Allison Freeman and center executive director Janneke Ratcliffe.

[ By Susan Hardy, Endeavors magazine ]