In a paper published today in the journal Nature Methods, a team from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill demonstrates a simple, cost-effective technique for three-dimensional RNA structure prediction that will help scientists understand the structures, and ultimately the functions, of the RNA molecules that dictate almost every aspect of human cell behavior. When cell behavior goes wrong, diseases – including cancer and metabolic disorders – can be the result.

Over the past five decades, scientists have described more than 80,000 protein structures, most of which are now publicly available and provide important information to medical researchers searching for targets for drug therapy. However, a similar effort to catalogue RNA structures has mapped only a few hundred RNA molecules. As a result, the potential of RNA molecules has just barely been developed as targets for new therapeutics.

“To effectively target these molecules, researchers often need a three-dimensional picture of what they look like,” says Nikolay Dokholyan, professor in the department of biochemistry and biophysics, and the project’s co-leader. Kevin Weeks, Kenan Distinguished Professor of Chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences and a UNC Lineberger member, is the other study co-leader.

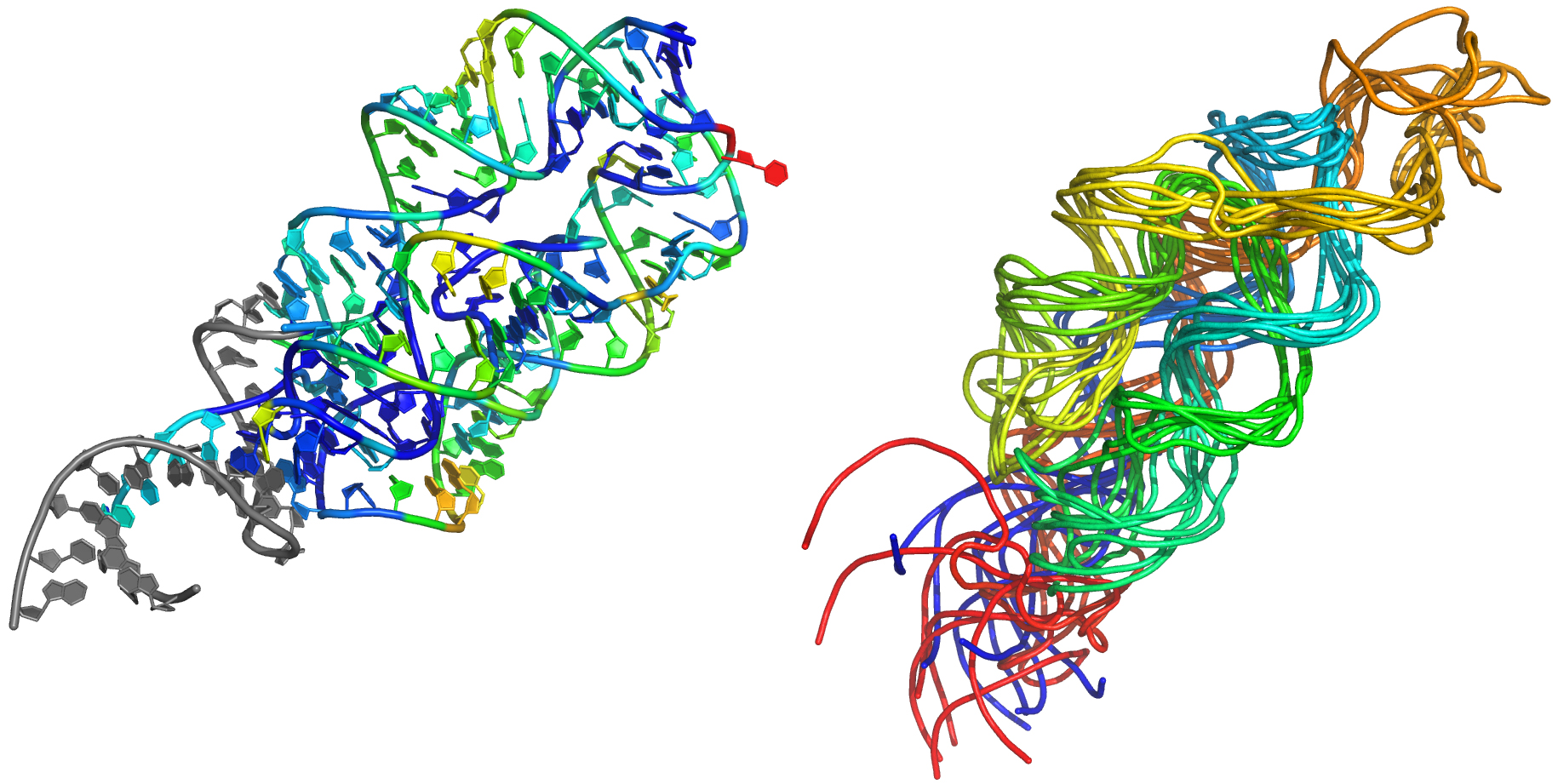

“With Dr. Kevin Weeks’ lab, we have developed a way to create a three-dimensional map of complex RNAs that are not amenable to study through other methods. It builds on information from a routine laboratory experiment, used in the past to evaluate RNA models from a qualitative standpoint. Our team has created a sophisticated quantitative model that uses this simple information to predict structures for large, complex RNA molecules, which have previously been beyond the reach of modeling techniques,” he adds.

Dokholyan, who is a member of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and director of the UNC Center for Computational and Systems Biology, hopes that the method will help researchers who are trying to target RNAs molecules to change cellular metabolism in a way that ultimately reduces the effects of cellular diseases like cancer. He notes, “Rational, cost-effective screening for small molecules requires a good understanding of the targeted structure. We hope that this method will open doors to new findings applicable to a wide range of human diseases.”

Other members of the research team include Feng Ding, Research Assistant Professor of biochemistry and biophysics,and Christopher Lavendar, a graduate student of in the department chemistry.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina Research Council.