The study also showed that each bird — regardless of size or species, or even the species of its neighbor — most commonly flew about one wingspan to the side and between a half to one-and-a-half wingspans back from the bird in front of it.

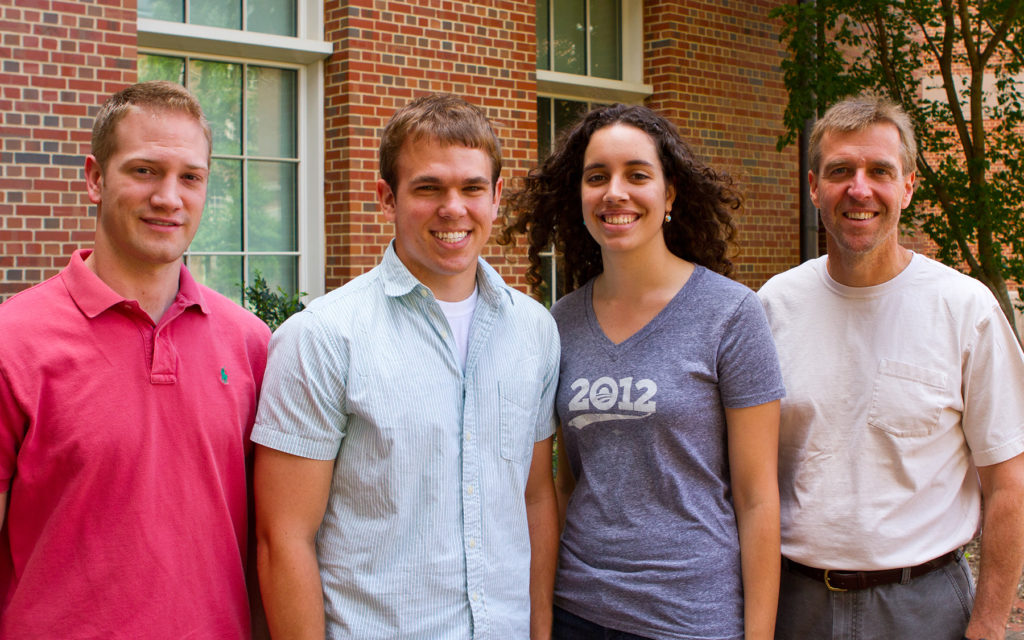

Wildlife researchers have long tried to understand why birds fly in flocks and how different types of flocks work. A new study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explores the mechanics and benefits of the underlying flock structure used by four types of shorebirds. Understanding more about how these birds flock moves researchers a step closer to understanding why they flock.The study, led by Aaron Corcoran, a postdoctoral researcher studying bat and bird flight and ecology, and biology Professor Tyson Hedrick in the College of Arts & Sciences at UNC-Chapel Hill, appears in the June 4 issue of eLife. The National Science Foundation funded the work.

In the study, the researchers focused on four types of shorebirds that vary in size: dunlin, short-billed dowitcher, American avocet and marbled godwit. Corcoran and Hedrick filmed and analyzed almost 100 hours of video footage to better understand the mechanics of shorebird flocks. They found that the birds fly in a newly defined shape the team named a compound V-formation, which they believe provides an aerodynamic advantage and predator protection.

This compound formation is a blend of two of the most common flock formations. One is a cluster formation, common with pigeons, where a large number of birds fly in a moving three-dimensional cloud with no formal structure. This structure is useful for avoiding predators. The second is a simple V-formation, commonly used by Canada Geese, where a smaller number of birds will line up in a well-defined two-dimensional V-shape.

“A flying bird creates downward-moving air immediately behind it and upward-moving air just beyond its wingspan on the left and right,” Hedrick said. “Taking advantage of this upward-moving air is all about positioning, and birds in the simple-V formation and compound-V formation are positioned correctly for aerodynamic advantage.”

To better understand the cluster-V formation and its mechanics, Corcoran and Hedrick recorded 18 cluster-like flocks of 100 to 1,000 birds flying over a bird sanctuary and agricultural fields during a migration stopover. The researchers measured the individual bird positions, flight speeds and even flapping frequency using three-dimensional computer reconstructions of the flocks from the video recordings.

“We thought we would find a trend in flock organization related to how large or small the different birds were,” Hedrick said. “Instead we saw that regardless of size, all these birds flew in the same formation – one that might let them get an aerodynamic benefit while flying in large groups, aiding their long-distance migration.”

Birds often fly in flocks ranging from very structured V-formations to loose clusters to improve flight efficiency, navigation or for predator avoidance. However, because it is difficult to measure large flocks of moving birds, few studies have measured how birds position themselves in large flocks or how their position affects their flight speed and flapping frequency.

The four types of birds studied in this project live in similar environments, but vary greatly in size, fly at different speeds, and have been evolutionarily separate for 50 million years. The birds mostly flocked with their own species, except for a few occasions where the godwits and dowitchers flew together in a mixed flock.

The study also showed that each bird — regardless of size or species, or even the species of its neighbor — most commonly flew about one wingspan to the side and between a half to one-and-a-half wingspans back from the bird in front of it. This flock structure, which is different from that of other flocking birds like pigeons and starlings, was termed a compound V-formation because birds flying in simple V-shaped formations follow similar rules.

By University Communications