While the United States and China take up roughly the same amount of land mass, China’s population is over four times that of the U.S. — and more people means more change in vegetation growth. How do these factors connect to climate change? Conghe Song explores this relationship, pursuing a project that has led to his return to his birthplace: rural China.

During the 1970s, in a rural village in the eastern Chinese province Anhui, a young Conghe Song and his family participate in collective farming to make a modest living. Countless hours are spent in the paddies cutting the plants by hand with a sickle and then replanting, literally one grain of rice at a time.

With no electricity, Song spends hours doing homework under an oil lamp. Each week, he spends a quarter for a candle so he and his classmates can work after dark — the cost, a burden on his family, he says.

Back then, college was the only way for Song to obtain a career beyond the village, but it was an uphill battle. Resources like financial aid and trained teachers went to the urban schools. He was fortunate to have a mother who was literate — at the time she was the only woman in the village who could read. She helped him with his homework and was strict about his education.

“I always admired the other kids in the village. They could go to school or not and they didn’t have the consequences I would have at home if I skipped school,” Song says, laughing.

Upon graduation, just two students from Song’s high school class of 54 went on to college — and he was one of them. Now a UNC geographer, his work has led him back to rural China.

Finding a niche

When Song began his college education in China, he was given the choice between four disciplines to pursue: medicine, education, the military, and agriculture. Growing up on a farm, he figured agriculture was a good choice, but later realized the topic wasn’t holding his interest. At that time though, because of China’s planned economy students couldn’t change their major. Once accepted by a university they had to stick with their chosen field of study.

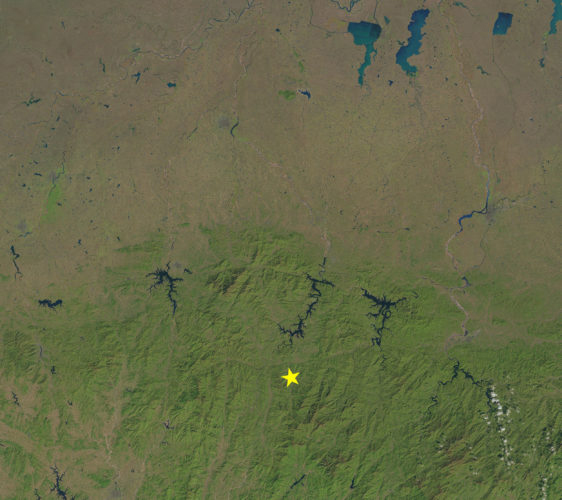

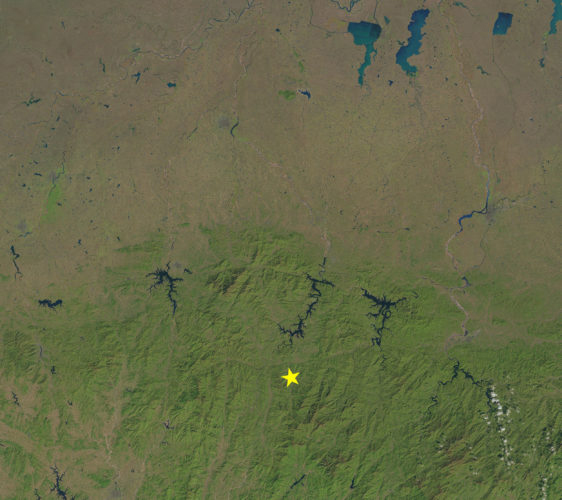

Luckily for Song, he discovered remote sensing — the use of satellites to observe the Earth — during graduate school in the United States. “That had the wow effect on me,” he says. “You have a synoptic view of the world that you can’t get on the ground. There’s so much information you can derive from the remotely sensed images, like the status of vegetation, and you can do this continuously for a large area and even for the whole world.”

As a physical geographer, Song uses remote sensing and ecological modeling to study how changes in climate, land use, and land cover affect the amount of carbon dioxide plants can remove from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. Factors that influence this can vary from climate stressors like drought, to human activities like deforestation.

Song realizes many environmental problems the world faces today originate from how humans change land-surface conditions. Loss of biodiversity and severe flooding? These are products of deforestation. Pollution? The huge amounts of fertilizers and pesticides applied to crops plays a large role.

That human element makes Song’s work incredibly interdisciplinary, and is why he teamed up with researchers at the Carolina Population Center, University of Virginia, University of Michigan, and colleagues in China.

Changing a landscape

Song returned to Anhui in 2011, but this time for work. For five years, he made annual trips to rural Chinese provinces to talk with farmers about their livelihoods, to see how their lives were influenced by recent environmental policies.

With over 1.4 billion people — over four times that of the United States — China is the most populous country in the world. This means it has the biggest conflict between human use and conservation of natural resources, according to Song. Because of this, degradation to the environment over the years forced the government to implement programs to restore and protect the land.

Immediately after the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, following the Chinese Civil War, the government made timber production the sole purpose of forest management. Their mistake, Song explains, was looking at the short-term economic benefits instead of the long-term consequences.

Two natural disasters in the late 1990s forced the government to change its ways. In 1997, the Yellow River — the second longest river in China — remained dry for 226 days due to drought, which led to huge economic losses, like the destruction of cropland dependent on the river’s irrigation system. The following year, historic flooding from deforestation killed more than 4,000 people.

In the wake of these disasters, the Chinese government established six forest programs to curb environmental deterioration, including some that encourage farmers to reforest croplands with little agricultural value in exchange for monetary compensation.

Song saw that the programs had impacts on both the environment and the local social systems, and wanted to learn the effects on both.

For three years, Song and his colleagues spent over one month each summer surveying both participants and nonparticipants in these programs. They used a 23-page questionnaire to gather detailed information on over 1,000 households.

Because the study concluded in 2018, the team is still analyzing data. So far, though, Song has noticed some promising trends.

He believes the programs were successful in improving the majority of participants’ lives as well as the local environment. Even before the programs, people didn’t rely on land for livelihood as much as generations before. Many people were actually happy to retire cropland and free up labor for improved and more diverse job opportunities. This means they will be less likely to use those lands again for crops after compensation ends.

Song is confident these findings will help persuade other developing countries to adopt similar programs.

Searching for balance

While Song is hopeful about environmental restoration programs in China, the results of another project have him worried about the future.

In 2015, Song and his team began a study on global greening — the increased growth of vegetation on Earth — through remote sensing satellite information. At first, the results were encouraging — the data suggested an upswing in growth.

Upon further evaluation, though, the team realized that more than half of the greening occurred in agricultural areas — a seemingly positive even undercut by massive deforestation in the tropics, especially in the Amazon. Furthermore, climate stress prevented photosynthesis rates from rising in tandem with greening rates.

Some may point out that more cropland accommodates an exponentially growing population, but Song cautions this notion.

“Right now, we do have enough food to feed people,” he says. “The real challenge is how to get the food to people in poorer countries, leaving important forests intact.”

For vegetation to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the rate of forest growth must increase. Crops absorb carbon, but it is recycled back into the atmosphere quickly, so it doesn’t help much to mitigate global warming. The most important type of vegetation for this is forest, which can store carbon for centuries if left undisturbed.

“First, we have to do a better job of protecting the existing forests, particularly old-growth forests in the tropics and developing countries,” he says. “And second, we need to have a more stringent policy to regulate anthropogenic carbon emission because we cannot rely as much on the natural vegetation to take up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.”

One of those policies, Song notes, is the implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement — a global effort to keep this century’s global temperature rise below two degrees Celsius, and help nations deal with the impacts of climate change. A part of that agreement includes the Green Climate Fund, which provides developing countries with financial aid to create more sustainable livelihood options for their citizens, instead of relying on deforestation.

The problem Song and his colleagues face is turning their knowledge into action.

“Unfortunately, for scientists, we’re very limited in shaping certain national and international environmental policies,” he says. “Look at global warming, right? The science is there, but policy makers have to ultimately make the decision for change, and not us. What scientists can do is provide them with sound, scientific knowledge and keep them informed and involved as much as we can.”

Song hopes that his work will help promote policies for reducing deforestation and carbon dioxide emissions worldwide, and promoting sustainable livelihoods in developing countries. If not, he believes potentially dire consequences can occur.

“You can continue to ignore it for one year, two years, for decades,” he says. “But eventually Mother Nature will get you.”

Conghe Song is a professor and associate chair in the Department of Geography within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences, and director of the Graduate Certificate Program of GISc.

Story by Megan May, Endeavors