Millions of Americans cast their votes every year, participating in a civic duty designed to make all voices and communities heard. But getting to the polls may not be as easy for some people as it is for others. UNC junior Chang Liu analyzed geographic data for approximately 224,000 Durham County voters and found widespread inequality in travel times to polling stations.

Chang Liu stands outside an Episcopal church on the wooded Kimberly Drive in Durham, clipboard and pen in hand. The date is November 7, 2017 — Election Day. As part of a political science class, he stops people as they exit, asking how they voted. As the voters come and go, he notices that, beyond the “I voted” stickers on their shirts, they all have something in common: Most are well-dressed, white, and seemingly middle class — which surprised him. Durham County is 38 percent black, 5 percent Asian, and 14 percent Hispanic-identifying, according to the U.S Census Bureau.

“It made me question the location of the polling station,” Liu says. “What if, in this precinct, certain people can’t get to the polling station because they are far from it?”

Voting rights aren’t a new topic in North Carolina. UNC researchers have studied voting accessiblity issues such as gerrymandering, voter ID laws, and early voting periods for decades. Political science professor Andrew Reynolds has analyzed elections of multiple governments and the impact on minoritity communities, North Carolina included. Current research also includes Christopher Clark, an assistant professor of political science, who studies the impact of electoral processes on black voters.

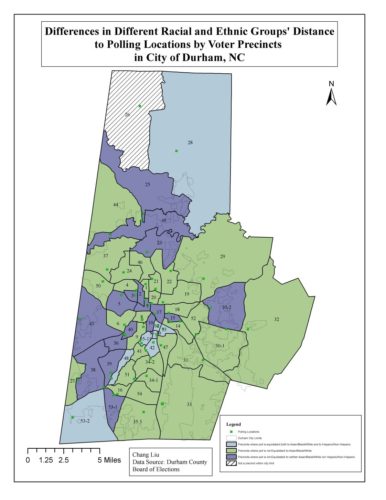

As a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship recipient, Liu took a spatial approach to evaluate the travel times voters of different races voyaged to their assigned polling station in Durham County’s 56 precincts. He used geographic information systems software and statistical analysis to individually map the county’s more than 224,000 voters to see if the major racial groups in Durham — white, black, and Asian — have equal access to polling stations.

“It is important interdisciplinary research that is timely and has significant implications to geo-politics and democratic institutions,” Xiaodong Chen, a UNC geographer and Liu’s research advisor, says. “While the project focuses on one particular election in Durham, North Carolina, the findings can have broader impacts on democratic practices in the U.S. and around the world.”

Liu intentionally designed his project to only indicate which precincts had inequalities and not specify which race or ethnicity suffered or benefited from them in his results. He wants people to unify and work together to rectify polling station inaccessibility despite race, not because of it. He believes that revealing any more than the existence of a problem in his project gives people the opportunity to use race as a reason to deepen divides in Durham.

“You only know that there is a difference, and all that matters is the difference, not which one is better off,” Liu says. “As a person who grew up in China and values unity, I find that in order to change things, you can’t do it just using the force of one specific group. You have to unify a lot of groups to get to your goal.”

Shifting viewpoints

China has a significantly lower ethnic diversity than the United States. Although the Chinese government recognizes 56 ethnic groups, only one — Han Chinese — makes up 92 percent of China’s population, according to a 2010 census. In comparison, the United States is 77 percent white and 23 percent minorities, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The demographic, cultural, and political differences between China and the United States challenged Liu’s perspective on race when he moved to California to attend high school as an exchange student in 2014.

“We never hear the notion of race in China, but you get to the United States and you’ve got a race,” Liu says. “Take me, for example — I’m Chinese, and when I got to the United States, I was identified as Asian.” He also discovered the prevalence of Asian stereotypes and realized people applied those labels to him.

Once Liu arrived at UNC as an undergraduate, he began to study and read more about race in the United States. In the spring semester of his first year, he took an American history class that discussed black racial stereotypes. After hearing accounts of racial profiling by police, he realized the extent of how stereotypes can impact people’s lives.

To learn more, he began reading novels with race-related themes and enrolled in “Race and Politics in the Contemporary United States,” the class that placed him in front of that Episcopal church in Durham.

Challenges and successes

Liu’s project began with data collection. “The most difficult part for me was communicating with different people to get things that you needed,” Liu says. “I had to go to the Durham County Board of Elections Office three times just to get the data.”

To generate the map, Liu gathered polling station locations, precinct boundaries, and the address, race, ethnicity, and assigned precinct of Durham County voters. He then converted the information for every individual voter into geographic latitude and longitude coordinates that could be placed on a map, a process called geocoding. With hundreds of thousands of voters, that’s a lot of data to process. “It took my computer a very long time — three hours,” he says, chuckling.

Next, he combined information about sidewalks, roads, and speed limits to create a network dataset, which connects those features in the map to calculate voters’ travel time to their polling station. After hitting a roadblock in making one himself, he went to the geographic information systems librarian at UNC, who gave him a more complete, accurate network dataset to use for his project. “I feel like a lot of the experience of this project was found by luck,” he says.

Once the map was completed, Liu calculated the quickest travel time for each Durham County voter. Now that he had the data, it was time to analyze it, which involved late nights meticulously transposing the numbers in spreadsheets for each of the 56 precincts. He used a statistical analysis model to measure the difference between racial and ethnic groups.

“The hypothesis was that Asian, black, and white races are equidistant to the polling stations. In that way, I could overlook the rivalry between the three racial groups,” Liu says. “It turns out that in the majority, 48 out of 56 precincts, there exists at least one group that is not equidistant to the polling station.”

In 86 percent of Durham County precincts, Liu found at least one race has to travel longer to vote than other races. He also discovered that in 30 percent of the precincts, non-Hispanic and Hispanic voters are not equidistant to polling stations.

A healthy skepticism

Once Liu got his results, the extent of inequality in accessibility to Durham polling stations surprised him. North Carolina law requires voters to vote in their assigned precinct’s polling station, but as Liu’s results reveal, the location of that polling station within the precinct may contribute to voter suppression. He feels his project could support the argument that this country’s free elections — a critical foundation for democracy — aren’t equally accessible to all.

Liu’s experience in China, a country whose political history and ideology immensely contrasts with that of the United States, influences the way he approaches his studies in political science. He’s more skeptical when analyzing political theory, unafraid to question the effectiveness and value of old-standing ideas and institutions — including democracy. To be clear, Liu doesn’t think democracy is a poor system of government, but it can be when it’s accepted as an absolute truth that people use to justify hurting others.

“My dad’s generation was raised up in the era that everybody believed communism was the way,” he shares. “But now, I find that here in America and in the minds of a lot of people in China, they think democracy is the only way.”

As he finishes his political science and geography degrees at UNC, he says he wants to keep an open mind and to question and think critically about what he learns to avoid entrapment in any rigid ideal.

“I think of college as process to learn how to discover and appreciate beauty and truth,” Liu says. “The former is driven by human’s intrinsic aspiration for beauty, and the latter is driven by pure curiosity and the undeniable right to pursue the truth. Geography provides me with the opportunity to appreciate the magnificence of nature and civilization, while political science fulfills my curiosity about truth.”

Chang Liu is a junior majoring in political science and geography within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences. This past summer he completed a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship, provided by the Office of Undergraduate Research.

Xiaodong Chen is Liu’s research advisor and an associate professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment, Ecology, and Energy Program.