Recently, the UNC Center for Community Capital (CCC) completed an assessment of lower-income people’s access to opportunity in two sites – San Francisco’s Potrero Terrace and Annex and New Orleans’s Columbia Parc. CCC’s opportunity assessment, funded by JPMorgan Chase & Co., took a two-fold approach: first, the creation of a data-driven index of place-based opportunity; and second, the use of community-level, qualitative research.

CCC combined quantitative and qualitative methods in order to uncover what factors cause people to engage fully with the opportunities that are available to them. The Area Opportunity Index created for this study helped assess the spatial distribution within communities of critical quantitative indicators of well-being that reflect present and past access to opportunity. However, we suspected that numbers alone might tell only a partial story of access to opportunity, and that we needed to talk to local residents and stakeholders to uncover the something extra that shifts “proximity” to “actual and beneficial use.”

It turns out our hunch was correct.

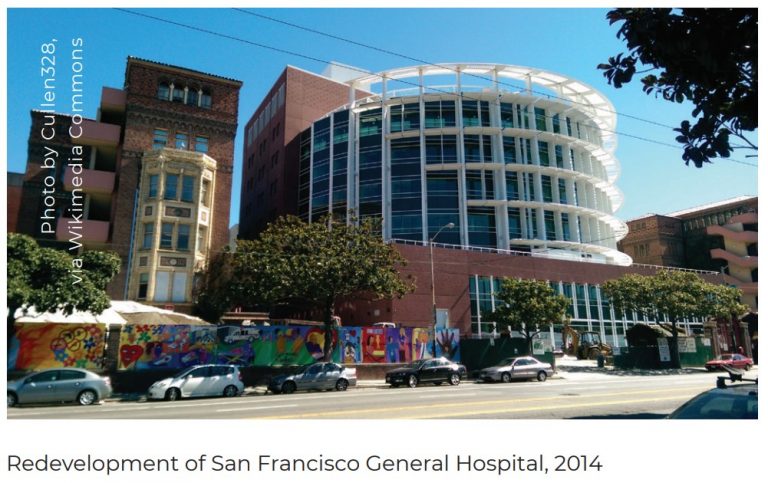

An example from the San Francisco site helps illustrate why qualitative methods are crucial to understanding access to opportunity. Potrero Terrace and Annex – a public housing development that is being redeveloped into a mixed-income community – is located within San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood. Potrero Hill occupies just over one square mile of land on the eastern side San Francisco Bay, and it stands out for being prosperous, even by San Francisco standards: the neighborhood’s median household income in 2015 was $147,700, over 80% higher than the median income for San Francisco County overall ($81,300).

Access to healthcare in the Potrero Hill neighborhood is excellent: as measured by our Area Opportunity Index, the vast majority (90%) of Potrero Hill residents ages 18-64 have health insurance coverage (according to the 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates). When we spoke with residents of Potrero Terrace and Annex, whose average income in 2017 was $16,557, most reported that they too have health insurance coverage. In addition to having insurance, residents are in close proximity to a health clinic: the Caleb G. Clark Potrero Hill Health Center is located on Wisconsin Street, within the Potrero Terrace and Annex Development, and it offers services five days per week. By the numbers, it would seem that the lower-income residents of Potrero Terrace and Annex have good access to the resources they need for their health care.

This is why we were surprised when a number of residents reported that they use the region’s emergency rooms to meet their healthcare needs. Digging deep beneath the numbers – asking follow-up questions of the interviewees we spoke with – helped reveal how what seems accessible can in fact be inaccessible.

Digging deep beneath the numbers – asking follow-up questions of the interviewees we spoke with – helped reveal how what seems accessible can in fact be inaccessible.

While some residents explained that the health clinic offers good access to care, other residents told a different story. They explained that while the clinic is close, it is difficult to obtain care from. As one person described, “The Potrero Hill Clinic that we have in our community, when we have different workshops, they always try to have people come to the clinic. But when the people start going there, they always say they can’t take no new patients, so they wind up sending people down to San Francisco General anyway. So people just get used to going straight down to San Francisco General, because they don’t want to go through the headache at their clinic.”

Further interviews revealed one reason for why Potrero Terrace and Annex’s health center is inaccessible to some residents: San Francisco’s health clinic assignment system disregards how close clinics are to where people live, resulting in decreased access to healthcare. As one interviewee told us, “The Department of Public Health [has a] very problematic [clinic] assignment system. Within that system, sometimes within a family, one family member may be assigned to one clinic, and another family member, say a mother, could be assigned to one clinic, and a child could be assigned to another clinic across town. So what we’ve noticed in this particular clinic assignment system is that it has, over the years, resulted in very small percentages of Potrero Hill public housing residents using that clinic that is literally across the street from where they live.”

Quantitative measures of access to opportunity – like our Area Opportunity Index – do a good job of painting a broad picture of the spatial distribution of indicators of access to opportunity. This picture is partial, however: it is only by digging deep beneath the numbers with in-depth qualitative interviews that the something extra that enables or inhibits access to opportunity might be revealed.

By Allison Freeman, UNC Center for Community Capital