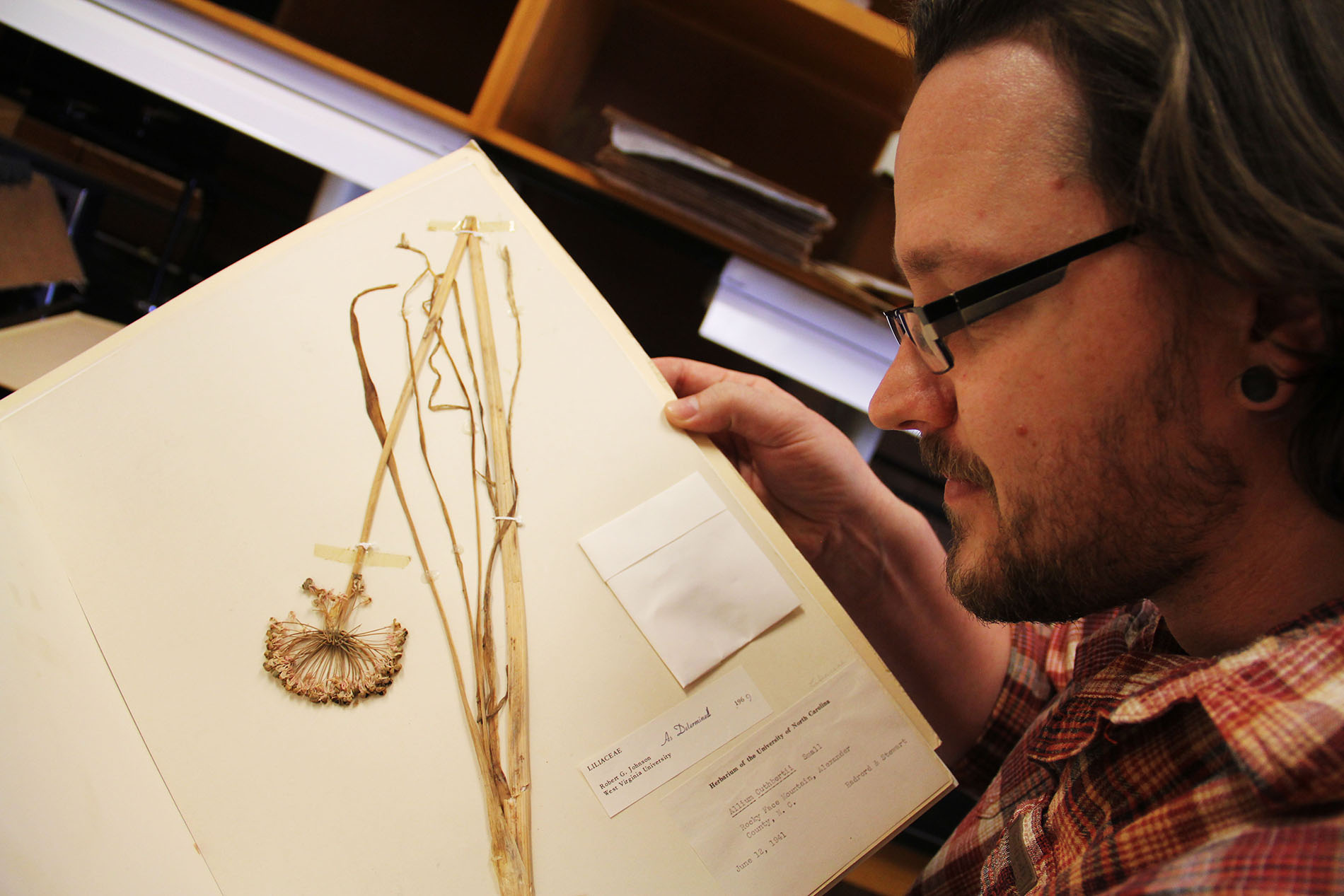

In the last 50 years, botanists have discovered more than 500 new species of plants across the Southeast. But it takes decades to actually study and record their existence — a feat that the UNC Herbarium has been tackling since its inception in 1908.

The main floor of Coker Hall looks like many other academic buildings on UNC’s campus: beige, plain, a little disheveled. But head to the first, third, or fourth floors, and you’ll find hallways overflowing with green cabinets — spillover from the UNC Herbarium. Each is packed to the brim with physical specimens of the region’s flora.

“When I was an undergrad at Carolina in the 1970s, the herbarium had already outgrown its space,” UNC Herbarium Director Alan Weakley recalls.

At 110 years old, the UNC Herbarium houses more than 800,000 specimens of plants, algae, and fungi. Managed by the North Carolina Botanical Garden, it has become the largest in the Southeast. “It’s a foundational resource for determining hotspots of biodiversity and where conservation is needed,” Weakley says. “You can’t conserve what you don’t know exists.”

Thanks to the ancient, diverse landscapes of North Carolina, finding new species of plants isn’t all that difficult. But classifying and naming them is a lot more complicated than one might think. Weakley estimates that the average time from the first collection of a new species to it formally being described is 20 to 30 years.

While new species are identified regularly, a lot of research goes into vetting them — taking physical measurements, completing statistical analyses, counting chromosomes, and extracting DNA for sequencing for hundreds of specimens. And these procedures take time, especially since most researchers are simultaneously knee-deep in other projects.

One recent example is Keever’s onion (Allium keeverae) — a plant that taxonomists once believed was a variation in Cuthbert’s onion (Allium cuthbertii), found from South Carolina to Florida. But when Weakley first came across the plant in the 1980s as a botanist for the Natural Heritage Program, instincts told him it was a different species altogether.

“It bothered me that these plants didn’t really match Allium cutbertii from the deeper South,” he says. “They were larger and had pink flowers, rather than white. And they were over 100 miles distant from the closest populations of Allium cuthbertii and grew in a distinctly different habitat.”

Weakley didn’t get to the fieldwork for this particular species until the last few years, when he, UNC graduate student Derick Poindexter, and undergraduate Parker Williams began analyzing the plant more in-depth. “Some of these plants in the Southeast are really cryptic,” Poindexter explains. Many lack obvious structural differences that help identify them as separate species.

“Because of climate change and human activity, we are in crunch time for biodiversity loss,” he continues.

“We’re living in a triage situation,” Weakley agrees. “Where should we be putting our effort in a world that is changing very rapidly, a world guaranteed to experience some extinction? All this cataloguing of plants sounds like a dry, dusty, academic process — but understanding the world around us is not dry or dusty at all.”

A rare find

While flower color offered the first clue that Keever’s onion may not be the same species as Cuthbert’s onion, other distinctions confirmed Weakley and Poindexter’s suspicions. Both the seed size and structure showed differences, as well as the length of the petals and stalks of the flowers.

Hundreds of years ago, the standard for deciding whether or not a plant was of a new species revolved around visual differences, according to Weakley. But more modern standards state that there should be proof that it is a separate evolutionary lineage.

Habitat also plays a role. “Cuthbert’s onion grows mainly in dry, acidic, sandy soils — mostly in the Coastal Plain and longleaf pine Sandhills,” Weakley points out. “Keever’s onion grows in rich soils in thin soil mats around rock outcrops restricted to the Brushy Mountains of North Carolina.” This suggests that Keever’s onion is an isolated, or endemic, species.

Because Keever’s onion exists in one restricted area of the Brushy Mountains, a remote range within the upper Piedmont spanning just two counties, it has been classified as a rare plant. Within that five-mile radius, though, there are many thousands of these plants growing on hard-to-access rocky hillsides. So, while rare and of strong conservation interest, the onion is not critically endangered.

What’s in a name?

Botanists who identify a new plant species have first rights to name it. “I think a lot of people interested in plants and animals assume that there’s a committee that decides,” Weakley chuckles. “But it’s really just this messy scientific process: Write a paper defending the hypothesis that it’s a new species, publish it in a journal, and then the scientific community will evaluate it over time and accept it or refute it.”

A pioneering ecologist, Catherine Keever graduated with a PhD from Duke University during WWII, a time when women were more readily accepted into graduate programs than before. “Her PhD dissertation was actually on one of the granite domes in Alexander County where Keever’s onion grows,” Weakley explains. “She encountered it and collected it and wrote about it in her papers.” But, at the time, Keever thought the plant was the same species as Cuthbert’s onion.

When Weakley first suspected Keever’s onion was its own species, he reached out to Keever — in her 80s at the time — about visiting its location in the foothills. On May 1, 1989, they drove up to the rocky outcrop and discussed the latest discoveries that had been made in the area since Keever conducted research there in the 1940s.

“I told her there had been some interest in this onion and that it might prove to be a rare species,” Weakley says. She has since passed away, and Weakley named the plant after her to honor her research career. To guarantee that her namesake and the other 800,000-plus species of the UNC Herbarium live on, staff and students are working rigorously to permanently preserve them — digitally.

Document and digitize

Documenting the flora of the Southeast sounds like tedious work, but it’s a fundamental component for discerning the entirety of an ecosystem. “We want to understand as many branches of the tree as we can,” Poindexter says. “Because when you lose portions of that tree or never recognize them as being there in the first place, it’s hard to make sense of it all.”

Will the extinction of a plant cause the collapse of an ecosystem? “Very unlikely,” Weakley says. “But each of these species is a result of a long and complicated history of tens and thousands of millions of years that led to that species being there. That concept of stewardship of the organisms on the earth keeps moving.”

Soon, researchers will be able to access and study each other’s specimens. Thanks to a push from the National Science Foundation, staff at the UNC Herbarium and 110 other herbaria across the region are digitizing their collections, which will be made accessible in an online portal.

“There really is a moral imperative to do this type of research,” Poindexter says. “It’s idiosyncratic but very exciting — we’re contributing in an innovative way to the rest of the community.”

Alan Weakley is the director of the UNC Herbarium (a department of the North Carolina Botanical Garden), as well as an adjunct associate professor in both the department of biology and the curriculum in environment and ecology within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences.

Derick Poindexter is a PhD student and graduate teaching assistant in the department of biology within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences, and a student assistant for the UNC Herbarium.

By Alyssa LaFaro, Endeavors magazine