In the late spring of 1847, a current of excitement ran through Chapel Hill: The president of the United States was coming to town. No such event had ever happened before. Moreover, he was a very special president. Though now of Tennessee, James K. Polk was a Tar Heel born (Mecklenburg County) and a Tar Heel bred, Carolina Class of 1818.

As a student, Polk had made an impression less by native intelligence than by the way he applied himself. To clinch an argument, his fellow students would say the point they were making was as surely true as “that Jim Polk will get up in the morning at first call.” An indefatigable self-starter, he was graduated with highest honors in both mathematics and classics; delivered a commencement oration in Latin; and finished first in his class. Since there were only fourteen students in the class, that may not seem much of a distinction. But consider that one of his classmates would become the governor of Florida; another, paymaster-general of the United States and consul general in Italy; another, president of Davidson College; yet another, bishop of Mississippi and chancellor of the University of the South. Among his fellow students in his Chapel Hill years were two future governors of North Carolina (one of them John Motley Morehead), as well as the future presiding officers of the Virginia and North Carolina Senates and the secretary of the navy who would be with Polk on his historic visit to Chapel Hill in 1847.

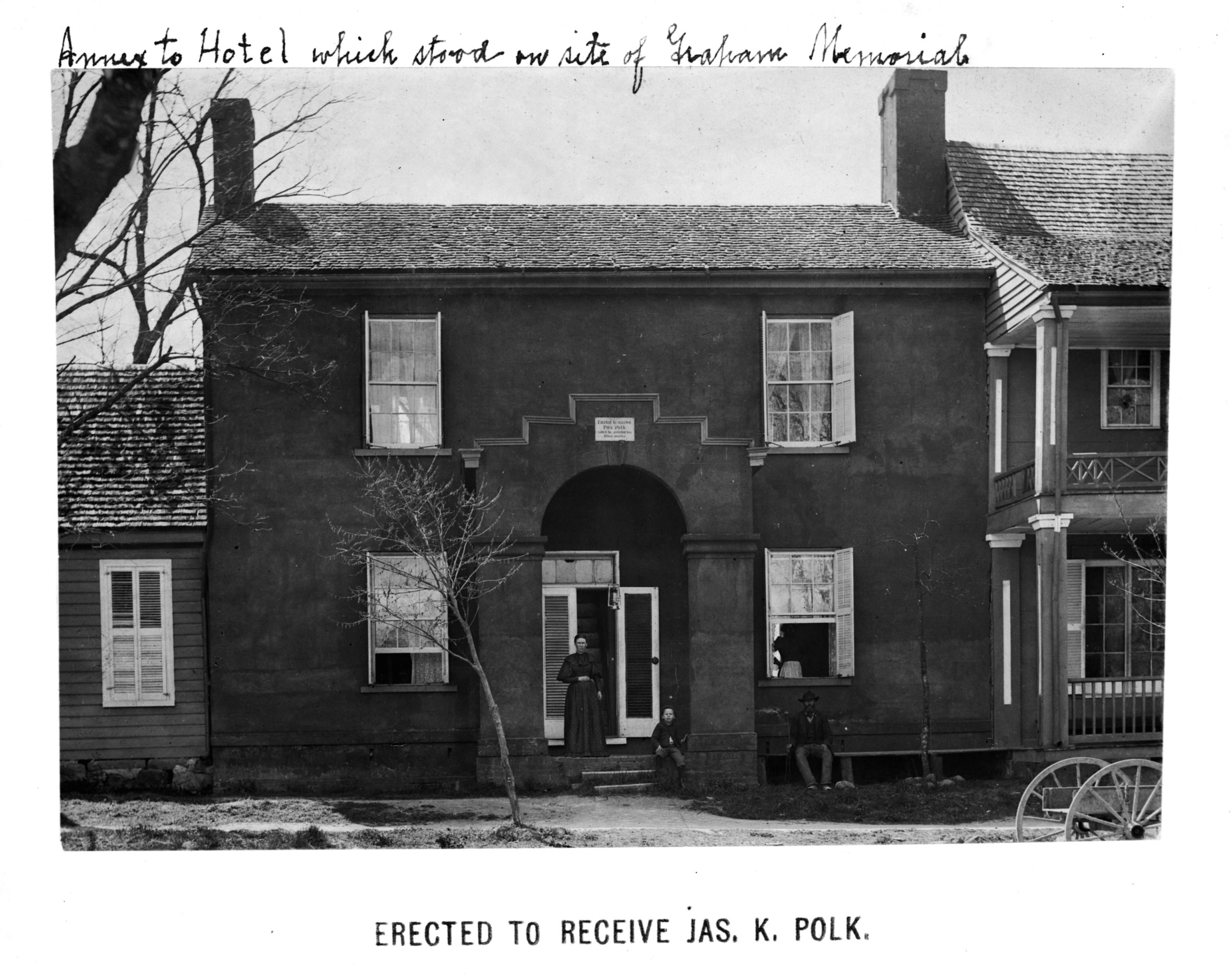

At eight in the morning on a warm spring day, the president and his entourage left Raleigh in a dozen carriages and other conveyances bound for Chapel Hill, a trip that required nine hours. He stopped often at farms to rest the horses and to shake hands with well-wishers, and took midday dinner along the route. Not until early evening did he arrive at the Eagle Hotel in Chapel Hill where, in his honor, the proprietor, Nancy Hilliard, had constructed an annex to house him and his companions. His large party included a naval officer: the brilliant Matthew Fontaine Maury — who was to win renown as “Pathfinder of the Seas” — the father of modern oceanography.

After checking in at Miss Nancy’s, Polk strolled to campus, where at the chapel, Gerrard Hall, he responded graciously — though with characteristic ponderousness — to an address of welcome from the president of the university, David Lowry Swain. It was “to the acquisitions received” at this university, Polk said, “I mainly attribute whatever success has attended the labor of my subsequent life.” Afterwards, he spoke to the only professor from his student years who remained: the noted scientist Elisha Mitchell, after whom Mt. Mitchell is named. Over the next two days, Polk renewed acquaintance with the campus. Accompanied by college chums, he reconnoitered the buildings of his youth, and with his wife returned to his old dorm room on the top floor of South Building, which had been completed only the year before he arrived as a student.

Polk’s stay came to a climax on Commencement Day, a magnet for hundreds of visitors. The correspondent for the New York Herald reported: “The little village of Chapel Hill is overflowing with people and they continue to pour in from all quarters, a number of persons having arrived all the way from Tennessee. There are tents pitched and wagons occupied by visitors, as at a camp meeting, for want of accommodations in the houses, which are filled to their fullest capacity, ‘Miss Nancy’ having the prospect of a thousand guests for dinner.” After observing the Class of 1847 graduated, the president returned to the White House, where he entered in his diary: “& thus ended my excursion to the University of N. Carolina. It was an exceedingly agreeable one.”

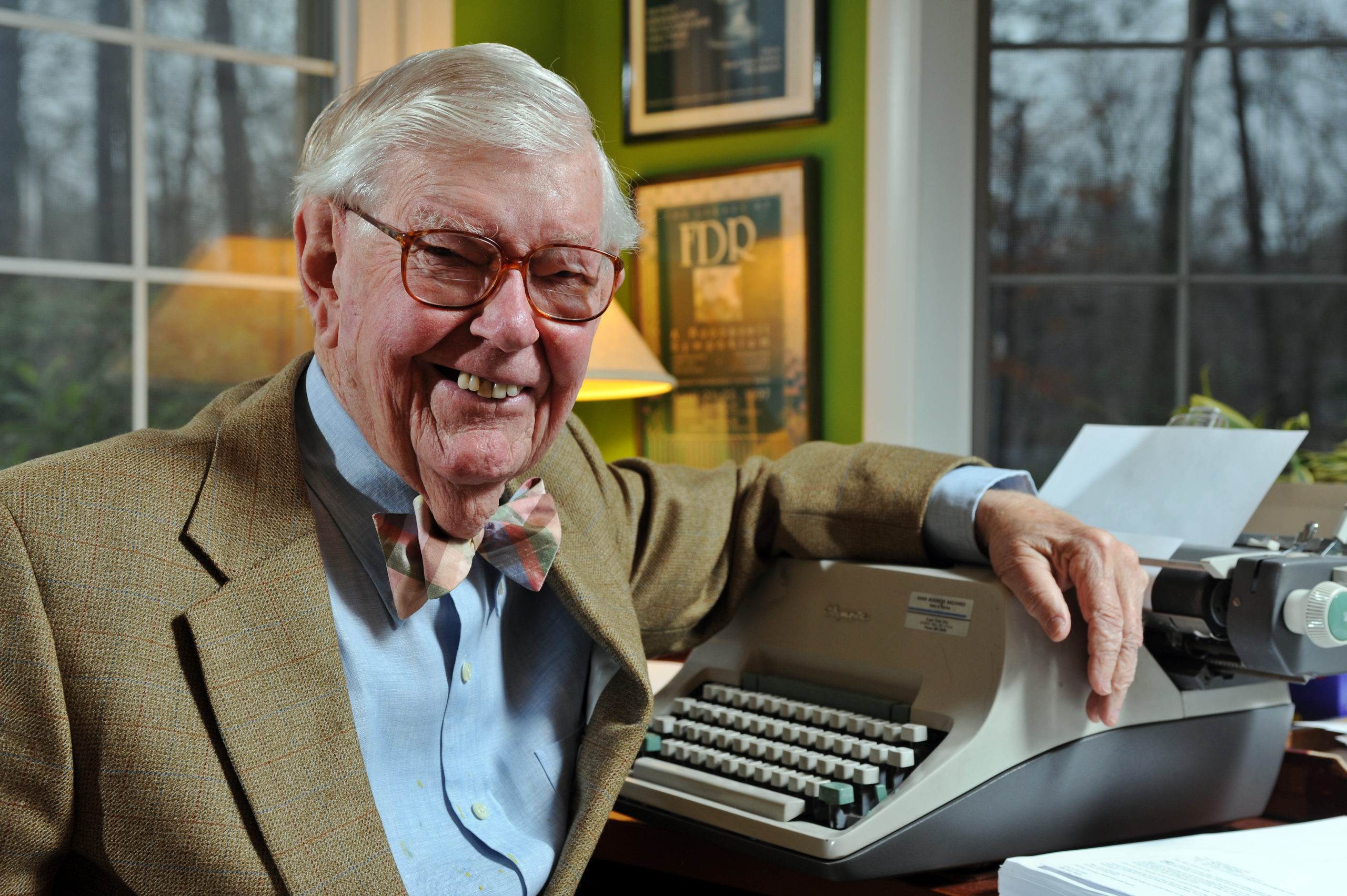

— By William E. Leuchtenburg. Excerpted with permission from 27 Views of Chapel Hill: A Southern University Town in Prose & Poetry, Eno Publishers, 2011. Leuchtenburg, William Rand Kenan Jr. professor emeritus of history in UNC’s College of Arts and Sciences, is a leading scholar of the presidency. He is the author of more than a dozen books on 20th century American history, including Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940. Printed in spring ’12 Carolina Arts & Sciences magazine.