Bill Andrews, senior associate dean for the fine arts and humanities, had never Skyped before, but he agreed to give it a go to continue meetings on the University’s new academic plan while his co-chair on the project, Sue Estroff, was away for the summer. He and Estroff, professor of social medicine at the medical school, wanted to stay on pace in creating the 10-year aspirational plan for the academic mission of the campus. They set up a practice Skype meeting, and he logged on at the appointed time.

He didn’t know about the webcam. When Estroff logged on, there was Andrews, shirtless and chagrined.

“He was as shocked as I was,” Estroff recalled. “But he got over it, and we had a good laugh.”

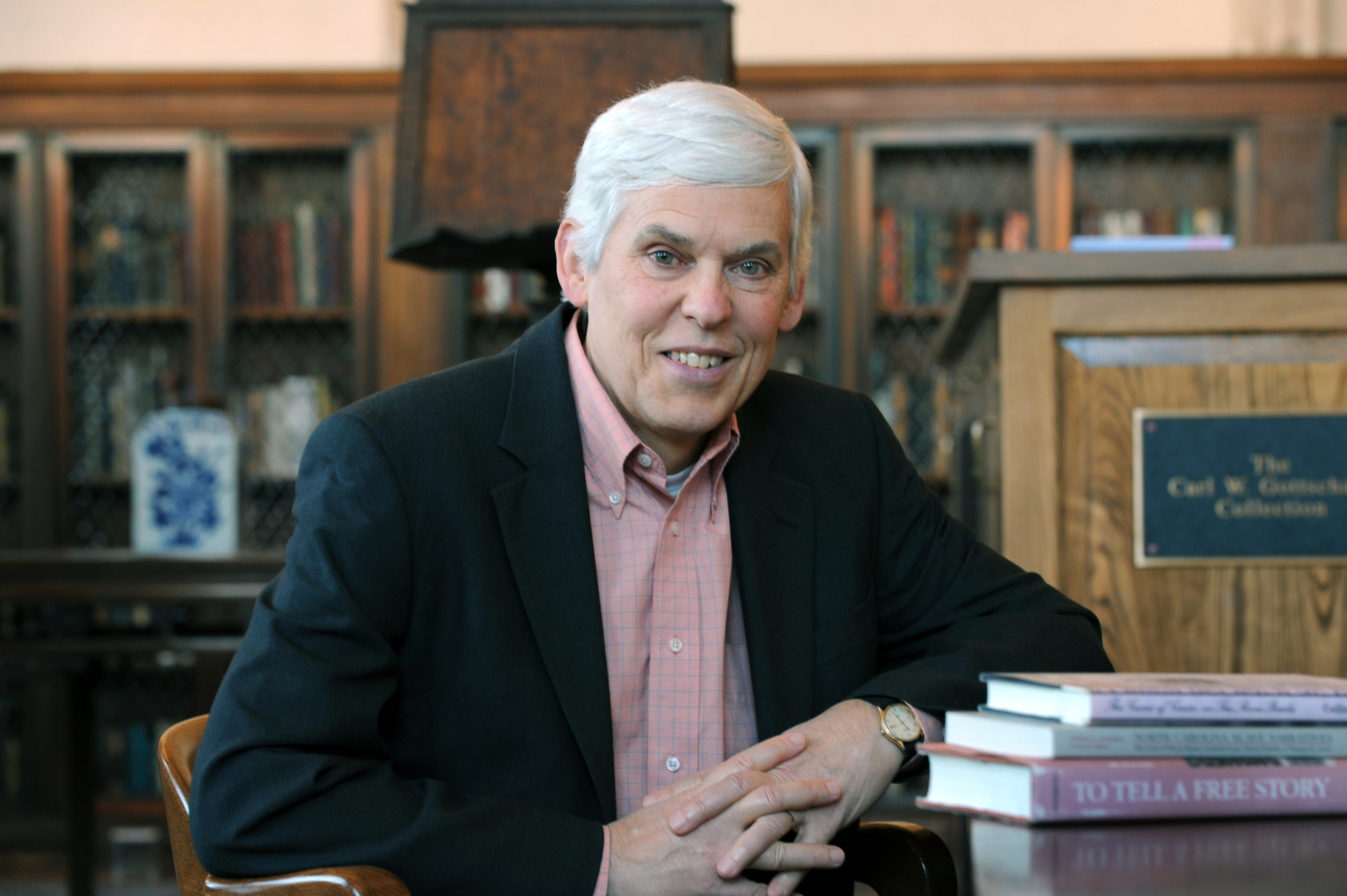

Andrews, a renowned scholar of African-American literature, will step down from the senior associate deanship at the end of the spring semester. After seven years in the post, a period plagued by a protracted recession and unprecedented budget cuts to the University, he nevertheless manages to leave the fine arts and humanities in very good shape. He has proven to be a stellar fundraiser for the College of Arts and Sciences, and department chairs say they will genuinely miss his advocacy and imaginative leadership.

The trust he has earned by working closely with faculty and administrators over the years has enabled him to sometimes deliver bad news without engendering resistance, said Terry Rhodes, former chair of the music department who will succeed Andrews.

“He’s very measured and fair and a great listener,” Rhodes said. “He responds quickly with timely decision-making, and he’s always at the ready to help our departments.”

Many responsibilities of a senior associate dean are tied to “money,” Rhodes said: budget allocations and reductions; reviews of instructional budgets; counteroffers and pre-emptive retentions of faculty; and fundraising, which has become increasingly important as state funding has declined and grants have become ever more competitive.

On an individual level, Andrews has written three grants to the Mellon Foundation that have brought in $7.1 million to the College. He’s been similarly successful in working with departments to bring in donations from alumni and friends.

Andrews has won admiration for advocating for faculty while budgets shrink. The number of tenured and tenure-track fine arts and humanities faculty has grown under his leadership, thanks to private support. He put together a professional development package for tenured associate professors that includes a research fund. He also led the creation of a promotion track for fixed-term (non-tenure-track) faculty.

Recently, Andrews has launched an exciting initiative to expand research and scholarship using digital media for the humanities, said Karen Gil, dean of the College.

“I’ll miss him a great deal,” Gil said. “He is an invaluable member of our senior leadership team for the College. He’s a great writer, thinker and planner. He works tirelessly to support the faculty and department chairs and help them advance their priorities.”

One of his colleagues, American studies professor Joy Kasson, agrees. Andrews has nurtured imaginative projects and encouraged departments to collaborate in national and international consortia. He takes a balanced approach to dealing with problems and opportunities.

“Even in times of financial constraint, his focus remains on what the College can and should do for students and faculty,” Kasson said.

Come summer, Andrews will return to his scholarly research — a study of class ideas and awareness in the autobiographies that African-American slaves wrote before Emancipation in 1865. And he’ll return to teaching — as the E. Maynard Adams Professor of English — after having been out of the classroom since he moved to the deans’ office in spring 2005.

A leading expert on African-American slave narratives, Andrews has written or edited numerous articles and about 40 books, including two published in 2011.

Jonathan Hess, director of the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies, pointed out that Andrews got his Ph.D. in 1973. “In those days, it was unthinkable that you’d make African-American literature your specialty,” Hess said. “He was a pioneer who went into that field when there was no field. That speaks volumes about how innovative he is as a thinker.”

Andrews also composes; he has set many Emily Dickinson texts to music.

Despite being extraordinarily productive and effective, Andrews doesn’t “walk around talking about how he has so much to do,” Hess said.

“The humanities are thriving at Carolina — that’s to his credit,” Hess said.

[Story by Nancy E. Oates, spring ’12 Carolina Arts & Sciences magazine ]