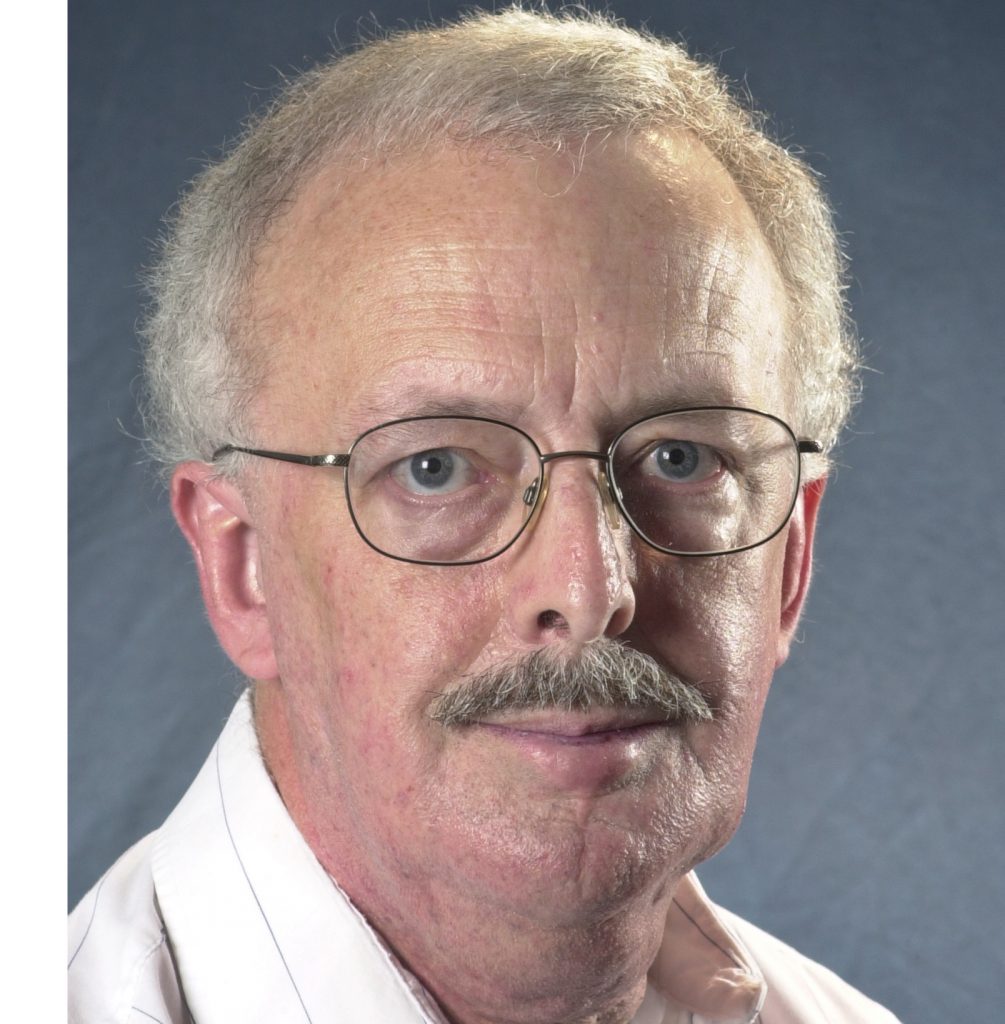

Stephen Walsh is Lyle V. Jones Distinguished Professor of Geography and director of Carolina’s Center for Galapagos Studies. He also is co-director of the Galapagos Science Center, a joint effort between Carolina and the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador, on Isla San Cristobal in the Galapagos Archipelago. Walsh and Jill Stewart, deputy director of the center, presented their work to the Board of Trustees July 24. Later, Walsh spoke with the University Gazette about that important research.

What projects are in the works at the center?

We’re looking at water quality in the islands. While it is still Charles Darwin’s paradise, the human dimension is very strong. About 30,000 people live on the islands and 223,000 visit each year. They face issues of urban infrastructure such as water quality, sanitation and wastewater management that we take for granted here in Chapel Hill. We’re also trying to gain an understanding of baseline body function of the marine iguanas and marine turtles that live there. That work with the animals is ongoing. A project I’m leading uses a 3-D scanner on a tripod to build ultra high-resolution models of different beaches, which are used by animals, tourists and residents, and looking at how different disturbances affect them.

What’s a conflict for the center right now?

There’s always something! It’s been forecast that this is going to be an El Nino year. El Nino changes the water temperatures of the Galapagos and has a dramatic impact on the survival of marine mammals like sea lions, marine iguanas and penguins. Warm water can kill the nutrients that support the fish populations, and that cascades through the food chain on which mammals are heavily dependent. No matter the severity of the weather, we’ll look at the change in the Galapagos through many different vehicles – people, communities, runoff, tsunamis and tectonic changes – to understand how these social and ecological systems are being disturbed.

How does this research influence students here at Carolina?

I teach “Human-Environment Interactions in the Galapagos Islands” in the fall, and many students end up coming to the Galapagos on our study abroad. Some on the trip will come back and take the class. When you go to the Galapagos, it reshapes you. There’s always something to discover – it’s amazing.

Students in Chapel Hill will learn about a place that began as pristine but is pristine no more, that was isolated for centuries, that allowed unique animals and species to develop. Issues of globalization are now affecting the Galapagos, so we are giving students a toolkit to understand people and the environment, as well as issues of adaptation, not just for animals, but also for people and policies.

Also, tsunamis have rearranged the sand on the beaches just as hurricanes have done in North Carolina. We’re looking at many of the same things, here, just different forces at work.

What’s it like to split your time between Chapel Hill and the Galapagos Islands?

I enjoy going back and forth. We have full-time faculty and staff at the center, so it’s important that I go when I can. I teach here in the fall, but spend a lot of the spring, and four to six weeks in the summer, at the center. It’s busy, but it’s very full, and that’s the way I like it! I was asked by the Ecuadorian government and the Galapagos National Park to come there, and Carolina has been able to offer them a fascinating perspective by applying our assets to the challenges that face the Galapagos – health, nutrition, biology and marine sciences, political science, geography, anthropology and more.

What would people be surprised to know about the Galapagos Islands?

That people live there! When most people think of the Galapagos they think of Charles Darwin’s paradise, the isolation and weird, wacky, wonderful animals. You can take cruises that go through the unpopulated islands, so you can visit and not have a sense that this is a highly, and increasingly, human-printed environment. It’s an ecological paradise with an expanding human dimension and all the challenges that go along with it.

By Courtney Mitchell, University Gazette. Watch a longer video of the center’s work here.)