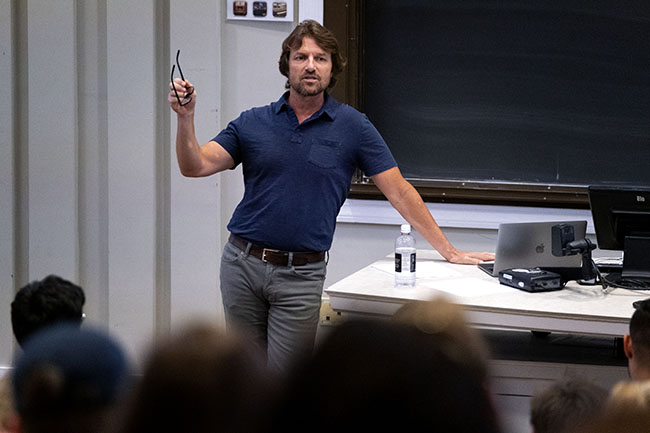

“We are not teaching information, we are teaching people,” says history professor Matthew Andrews. “And for information to come alive, most people need to hear a story.”

(Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

The key to good teaching, historian Matthew Andrews believes, is knowing how to tell a good story.

What has often surprised – and delighted – his students over the years has been his ability to shed light on darker aspects of the American story through the lens of sports.

“We are not teaching information, we are teaching people, and for information to come alive, most people need to hear a story.”

And ever since Andrews joined Carolina’s history department as an associate teaching professor in fall 2012, that’s exactly what he has been doing.

In his “Baseball and American History” course, he captures the story of Jackie Robinson, the player who broke the baseball color line in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Historian and social critic Manning Marable would write about how Robinson became a “symbolic representation” of his race; others who carried this burden included boxer Joe Louis, track star Jesse Owens and tennis player Arthur Ashe.

For his “Sport and American History” course, Andrews gave a lecture titled Sports and Race in the 1980s that revealed the racial tensions of the era by examining the epic rivalry between NBA stars Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, and the 1982 heavyweight championship fight between Larry Holmes and Gerry Cooney.

Andrews knows that many of his students sign up for the course because they think it will be easy or fun because they are interested in sports, but not history.

He disavows them of that idea on the first day of class, which always begins with a sports quiz.

“We go over their answers, and we have a great time, and then I tell them, ‘Take that paper and throw it away because that’s sports trivia. It’s fun to do, but it’s a bar game. This is a classroom.’”

Connecting with students

But his is a classroom that students clearly like.

His reputation for excellence in teaching has been affirmed again and again by students who, for four consecutive years, have nominated him for the Chiron Award. (The award’s name comes from mythological Greek centaur-teacher who sought to inspire the pursuit of wisdom and enlightenment in those around him.)

Andrews won the award three of the past four years, including this year.

(Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

This year, The Daily Tar Heel also designated Andrews as “Best Professor” for the third time. The student newspaper also cited several of his courses as “Best UNC Class” over the years, including “History of the Olympics” and “Baseball and American History.”

Andrews now teaches an introductory seminar about teaching to incoming graduate students.

“I can be a pretty laid back, mild-mannered guy, but I always end with this notion that there is no such thing as too much enthusiasm in a class. You can never be too energetic because students absolutely feed off it.”

Andrews said the intent of his lectures is to provoke and engage. He pauses regularly to respond to questions.

What makes the story of sports such an effective way to engage students in history is that it is an area of public life that joins people together in a shared experience that is often powerfully felt and creates memories that can last a lifetime.

Before the Holmes-Cooney fight, for instance, Andrews remembers reading all the media hype about Cooney’s chances, as a white challenger, of beating Holmes, the black champion. Sportswriters billed Cooney as “The Great White Hope.”

Andrews, who was a teenager at the time, said he does not remember consciously rooting for Cooney because he was white, or against Holmes because he was black. Yet, by following the lead of the media, Andrews had subconsciously internalized the prevailing idea about race and “naturally” gravitated toward Cooney.

That spell was broken, Andrews said, when he heard Holmes tell Cooney “Let’s have a good fight.”

“That’s how insidious it was,” Andrews said. “It was all so unthinking, and it took Holmes’ sportsmanship to snap me out of it.”

“I tell my students that story,” he added, “in hopes of prompting them to consider how sports informs their own thinking about race in American society.”

Repeating history

The students who experienced Andrews’ passion as a teacher would be surprised to learn how much of an indifferent student he once was during his undergraduate days at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“I was a history major, and —I got to be honest — I wasn’t terribly interested in American history at the time,” Andrews said.

It would take a decade and a series of odd jobs that included a stint as a kindergarten teacher in his hometown of Oakland, California, before his growing interest in politics and civil rights triggered a real interest in American history, he said.

He got his master’s degree at San Francisco State University, where he met Jules Tygiel, a historian and self-confessed baseball nut. Tygiel’s Brooklyn upbringing inspired his highly regarded scholarship on Jackie Robinson.

Like Tygiel, Andrews grew up loving sports. Andrews rooted for nearly all the teams in the Bay area, especially the San Francisco Giants, because they had been his father’s favorite team.

When he found out that Tygiel taught a college course on Baseball in American History, Andrews asked him, “Wait, you can do that?”

That changed everything.

After earning his doctorate in history from Carolina in 2009, Andrews taught at Guilford College until he joined the history faculty here.

The popular course that Andrews now teaches is much like the one Tygiel taught, using baseball to explore topics ranging from industrialization, conflicts between labor and capital, racial prejudice and integration, patriotism and the American identity.

In the course syllabus, Andrews captures the objective of the course with this quote from writer Roger Angell: “Baseball seems to have been invented solely for the purpose of explaining all other things in life.”

Andrews said there are two things that students often say to him that give him the most satisfaction.

The first is some variation of “I never liked history before this course and now I am fascinated.” The second thing is when a student tells him, “I called up my grandfather and asked him about this story you were just telling us about, and I had the best conversation I’ve ever had with him in my entire life.”

Post by Gary Moss, The Well