In 1776, how many colonies did Britain have in North America? If you said 13, you’re only half right. The number is actually 26.

Any graduate of a high school U.S. history class can tell you the basics of the American Revolution, how 13 British colonies declared their independence and fought a war to win it.

But most Americans, and even some historians, have no idea what was happening in Britain’s other 13 colonies at the same time and what effect that had on the revolution. Who knew that Revolutionary War battles were fought in Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans? American historians often neglect the battles in the Gulf region, where the British were fighting on a second front with the Spanish, and the impact of alliances of American Indians with either the British or rebel forces.

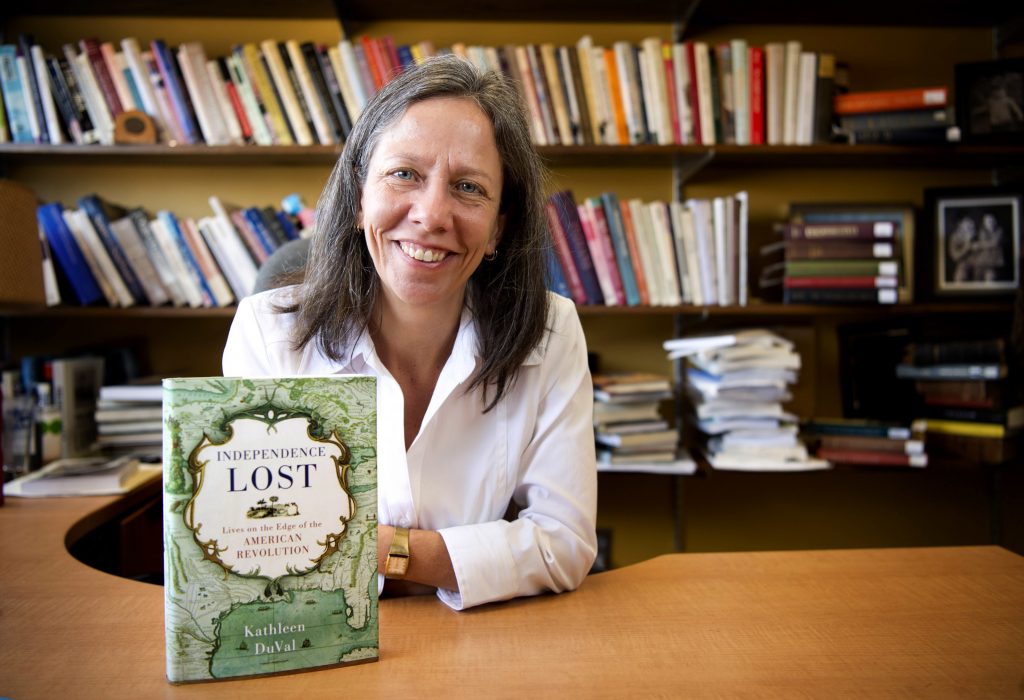

Kathleen DuVal, history professor and adjunct professor in American studies, sought to fill that gap in knowledge with Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution (Random House).

“I wanted to write about the revolution in a place that people didn’t usually think of as being part of the revolution because that wasn’t where the action was,” DuVal said.

Both mainstream book critics and historians have praised her book. “Independence Lost will knock your socks off,” raved The New York Times Book Review. “To read [this book] is to see that the task of recovering the entire American Revolution has barely begun.”

Independence Lost was named the Journal of American Revolution 2015 Book of the Year and winner of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey History Prize.

Now it is a finalist for the George Washington Book Prize, one of the nation’s largest and most prestigious literary awards. The $50,000 prize recognizes the past year’s best-written work on the nation’s founding era. The winner will be announced at a gala dinner at Mount Vernon in May.

DuVal’s reasons for writing the book were the same that first drew the scholar to early American history. “I was interested in the different ways that history could have gone,” she said.

Knowing how the Revolutionary War turned out, many Americans assume that the rebel victory was inevitable. But not DuVal.

“Why did we come out on top? In some ways it’s the least likely outcome,” she said. “If I’d been a betting person, I would have bet on the British. If I’d been a colonist, I wouldn’t have been a rebel. It was crazy. They had a pretty good deal.”

Knowing the sad fate of American Indians and the relentless expansion of settlers onto their lands, Americans tend to discount the role indigenous people played in the revolution. But in 1776, the continent was still mostly populated with American Indians, different tribes in different alliances: some with the colonists, some with the British, some with the French, some with the Spanish and some desperately trying to remain neutral.

Slaves and women also played roles in the revolution, stories that are seldom told but remain tangible reminders of the hypocrisy of the Founders’ flowery language about “independence” and “equality.”

“It is such a complicated story,” DuVal said. To tell it, she decided to approach it more like a novel, finding historical characters with interesting stories of their own who could also stand in as representatives of certain groups.

“I like reading fiction more than I like reading history,” she said, adding, “most history.”

She settled on eight people readers could follow through the book: a Mobile slave seeking his freedom, a diplomatic Chickasaw Indian trying to avoid conflict, a young Cajun militiaman, one married couple in New Orleans who allied themselves with the rebels and the Spanish against the British, the son of a Creek mother and a Scottish trader trying to rally the Creeks to support the British and a West Florida couple loyal to Britain and under attack from Spain and the rebels.

DuVal’s topic brought specific challenges. White, literate males left behind plenty of documents to study “if you can read French and Spanish and bad handwriting,” and she can, she said. But the women, slaves or American Indians she was most interested in left little documentation.

“The women wrote letters that weren’t the kinds of things that families saved,” she said, acknowledging that even mundane missives about the weather, fashion, furnishings, customs and food would be a treasure trove for historians.

And most slaves were illiterate and kept that way by law. But she found that the Spanish left several records about Petit Jean, a slave that they recruited to spy on the British.

Through these real-life characters, DuVal immerses the reader in a part of Revolutionary War history that is unfamiliar territory. The convincing way she tells her story makes the reader almost as surprised today by the rebel victory as the rest of the world was in 1783.

By Susan Hudson, Gazette