For all those members of the Class of 2014 who are eyeing the May 11 graduation date like it just won’t get here soon enough — you are not the first Tar Heel to experience “senioritis.”

Apparently the condition has been around a very long time. While it’s not possible to ask a student from the antebellum period about it, James Lawrence Dusenbery provided some insight in his personal journal documenting his senior year here from 1841-1842. Now you can read his words online.

UNC scholars, librarians and graduate students launched the digital humanities project, “Verses and Fragments: The James Lawrence Dusenbery Journal,” in 2011 as part of the Documenting the American South online collection, an initiative of the UNC Libraries that provides Internet access to texts, images and audio files related to Southern history, literature and culture. The idea to publish Dusenbery’s journal originated with Erika Lindemann, professor of English and comparative literature, who discovered the journal during research for another DocSouth project, “True and Candid Compositions: The Lives and Writings of Antebellum Students at the University of North Carolina.”

Why focus on Dusenbery, an average student who was a native of Lexington, N.C.?

For one thing, Lindemann wanted to find a journal that would outline an entire year in a student’s academic life from that period. Dusenbery was not “famous,” but that’s precisely the point, said Lindemann, who is also associate dean for undergraduate curricula in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“History is told in the voices of ordinary people as well as college presidents,” she said. “The reason we are here is because of the students, so where are the students’ voices in the history of the University?”

And yes, Dusenbery did experience a bit of senioritis, even toward the start of his school year.

“The Di end of the West Building has always been characterized as the noisiest part of College & well does it deserve the appellation. … The noise was chiefly in my room on Monday night. Five of us were fighting with pillows. Beds were tumbled, hats crushed, my pillowcase torn to pieces & finally the candle thrown down & extinguished, when darkness put an end to the frolic.” – August, 29, 1841, from Dusenbery’s journal

“He’s much more interested in his social life than academics,” Lindemann said. “He loves playing cards, going hunting, drinking, visiting the women of the town.” Yet, despite an active social life, Dusenbery did manage to graduate, attend medical school, and live out the remainder of his life as a physician in Lexington.

The Dusenbery collaborators received some recent good news. In February, they learned that the site has been accepted for inclusion in NINES, a peer-reviewing organization that evaluates 19th century British and American digital projects and supports scholars’ best practices in the creation of those materials. It was important to Lindemann that the site undergo the same rigorous process that an academic journal article would receive in order to encourage younger scholars to publish digital humanities works.

The Dusenbery Journal joins only 127 federated sites that have been peer-reviewed by NINES. The William Blake Archive (with UNC English professor Joseph Viscomi as one of the co-editors and creators) is also a NINES peer-reviewed site.

“What attracts me to these digital humanities projects is that they truly open the doors to traditional scholarship to the general public,” said Natasha Smith, a former UNC digital librarian and co-director of the Dusenbery project. “There are no geographic or educational boundaries. You are not intimidated by the information. One of the goals of DocSouth is to make these collections as user-friendly as possible.”

Dusenbery’s world

In addition to being able to read the journal online, project creators wanted to enhance readers’ experiences by creating a “His World” section that illuminated six areas of 19th century Southern life — family, student life, debating societies, medicine, literature and music. The first half of Dusenbery’s journal consists of poems and other literary works that he copied down; in the second half, beginning on page 78, he chronicles the activities of his senior year.

Each module showcases a scholarly essay on the subject and supplementary materials — photos, maps, audio files — that give users an opportunity to dive deep into history of the period.

What was student life like for a senior in 1841? According to the University catalogue, students in the first session studied the sciences, Greek and Latin, mental and moral philosophy, and French. In the second session, they continued studies in Greek, Latin and French, but also added law, political science, chemistry and geology.

Dusenbery has this entry about fall session grades:

“The reports were made out last Monday. Mine was tolerable on Astronomy, very respectable on Greek & respectable on French, Chemistry and Political Economy.” — October 3, 1841, from Dusenbery’s journal

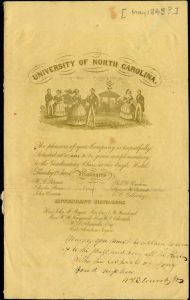

All students were members of a debating society, either the Dialectic Society or the Philanthropic Society; Dusenbery was a “Di.” Students were required to go to chapel. Upon graduation, students were invited to attend a commencement ball.

“There were no majors; you got a degree from the University and from your debating society,” Lindemann said. “Every student was exposed to the same curriculum, and it was because the purpose of higher education was not to prepare you for a job, which tended to be medicine, teaching or law. It was intended to prepare you to be a leader in society.”

Literature

Oprah has her reading list; the Dusenbery project also offers readers a look at Dusenbery’s reading list.

Sarah Ficke, a former UNC English graduate student who worked on the literature module, said if Dusenbery’s list seems to be missing what we might consider “classic” American works of literature, it’s because many of those were published after he graduated. In fact, most of the works he mentions are British.

“There was a lot of British poetry. It partially had to do with what was being printed at the time, with copyright laws, but there was also a sense that American literature was still developing its unique characteristics,” said Ficke, who today is an assistant professor of literature at Marymount University in Arlington, Va. “Dusenbery was really interested in the extravagant, romantic tales of chivalry and heroism and love, so the books he was reading cluster around those themes.”

Music

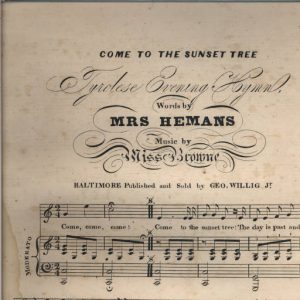

Several themes emerge in the music that surrounded Dusenbery’s world: music from the stage, popular music, sacred music, and music from brothels. But given Dusenbery’s geographic location, there’s also some music specific to the region, such as revivals and singing schools, which were popular in the South.

Douglas Shadle was a UNC graduate student of music who worked on that section of the project; today he’s a visiting professor of music history at the University of Louisville. He also compiled Dusenbery’s music list. Want to listen to some of the music of the day? You can do that, thanks to audio clips embedded throughout that section of the site.

“One of the amazing things about the time period of this journal is that the 1840s was really when the sheet music industry in the United States started to take off. Once Stephen Foster gets on the scene, things really begin to explode,” Shadle said. “Now we have YouTube and iTunes for sharing music, but then it was sheet music. It was bought and sold and shared from person to person.”

Medicine

The topic of Dusenbery’s senior speech — “The State of Medical Sciences in N.C.” — is indicative of his desire to become a physician after graduation.

He talks about the dread of writing that senior speech in this entry:

“I have done nothing as yet towards writing a speech … To write a speech for the first time & one too that is to be spoken before an intellectual and severely critical assembly is, to me, a task of ‘fearful magnitude and startling responsibility.’” — October 10, 1841, from Dusenbery’s journal

Former UNC English graduate student Ilouise Bradford worked on the medicine section of the site. Bradford is now an editor at American Journal Experts, which helps international scholars eliminate language barriers and get their work published in top journals.

After graduation from UNC, Dusenbery went on to attend the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school after spending some time studying with Lexington physician C.L. Payne, a family friend.

“You usually had to spend a year or two with a practicing physician and that was part of your entrance exam in a way,” Bradford said.

What were the medical challenges of the day?

“Pain management was something doctors were always thinking about; chloroform and ether started coming into play in the mid to late 19th century, but even then it wasn’t always used because anesthetics were generally reserved for white women and children of the upper classes,” Bradford said.

Bradford and Lindemann both contributed to the medicine module. Collaboration, a critical component of digital humanities initiatives, was part of the appeal of the project for Lindemann and her colleagues, as well as the opportunity to take an in-depth look at one person’s life.

“The team together would come up with different ideas,” Lindemann said. “If you think about history as sort of building fences around a period, Dusenbery’s Journal is a fence post. It goes deep into one student’s academic career.”

[ By Kim Weaver Spurr ’88 ]