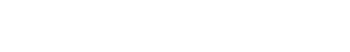

Daniel Anderson has been at the forefront of computer-based teaching and learning for decades and helped develop IDEAs in Action, the new general education curriculum to be implemented in fall 2021.

In Daniel Anderson’s English classes, the students don’t just write term papers. Class projects in one of his introductory courses include podcasts, mashups, videos and screencasts. That’s because this distinguished English professor also directs the Digital Innovation Lab and is co-principal investigator of the Carolina Digital Humanities Initiative.

Anderson has been at the forefront of computer-based teaching and learning for decades and helped develop IDEAs in Action, the new general education curriculum for undergraduates that will be used in fall 2021.

The English professor became an early adapter of technology almost by accident back in 1994. He entered graduate school at the University of Texas planning to get a doctorate in poetry, but his adviser had a different idea.

The English department had received a grant to start a computer lab for classroom instruction. If Anderson could figure out how to teach with those computers, his adviser suggested, it could help him get a job quicker.

And with that advice, Anderson’s life and career took a new turn.

Joining the revolution

Anderson’s early embrace of technology helped prepare him for the challenges and opportunities to come. He has always been in search of what he calls “the sweet spot” — that fertile space between the familiar and the unknown where magic can happen.

“It was beneficial for me to have begun with both feet firmly planted in print literacy and a love of language,” said Anderson, now the Zachary Smith Distinguished Term Professor in the English and comparative literature department.

Anderson joined Carolina’s English department in fall of 1997, weeks after then-Chancellor Michael Hooker announced the Carolina Computing Initiative, which required undergraduates entering the University in fall 2000 and later to have a laptop computer. (To ensure equal access, every first-year undergraduate student receiving need-based financial aid also gets a laptop grant to cover the cost.)

Anderson joined a select group of professors who developed pilot courses to show students how to use these computers.

In his pilot seminar, students explored how technology influences the study of literature, using the hypertext capabilities of the web to put together critical remarks and annotations that were less accessible in traditional formats. The computers also allowed students to talk about their ideas both in and out of class.

Redesigning the curriculum

All of it may seem a bit quaint in today’s smartphone era, but then he was stepping into a world that would fundamentally change the instructor’s role, Anderson said.

Those changes are reflected in IDEAs in Action. Anderson served three years on the coordinating committee that helped shape the new curriculum.

“We are shifting the focus away from somebody standing in front of students and lecturing to creating opportunities for student to work on something or make something on their own,” he said. “No matter what the context, we know the ability to collaborate and to work iteratively will be helpful to them. So much of it is about critical thinking, the ability to analyze and make judgments that you can learn from studying Shakespeare or Picasso or any other subject matter.”

New forms of scholarship

In his research, Anderson is experimenting with videos and screen composing to create a new form of scholarship about multimedia through multimedia.

“The book I am working on now is actually a collection of videos, and the only rationale behind calling it a book is so that it can be recognized as scholarship in university structures,” Anderson said.

“Those videos are allowing me to track what is going on with our lives and our intellects with technology because they are based on the computer screen as a composing space.”

Video scholarship—which adds images, sounds and motion to academic writing—focuses on ways of knowing that are “windowed, layered and multimodal,” Anderson said. The images, sounds and motion allow for ambiguity and affect that words cannot.

“Scholarship based on video and screen composing may open up alternative modes of thinking that move beyond words into the realm of sensing and feeling. If I play a video so people can hear a baby cry or the sound of the ocean, they are likely to be moved in a different way than they would by a logical, philosophical argument.”

A playlist for ‘Pi’

As one alternative to a written essay, Anderson asks his students to create a playlist of songs appropriate for a character’s experience in a literary work. The exercise engages students with sonic literacy

“The book, The Life of Pi, for instance, has a character on a boat with a tiger in the middle of the ocean, and if a student would put ‘Eye of the Tiger’ on a playlist, I would say, ‘Stop and listen to that song that starts with these loud guitars. Does that fit the experience of this young boy who has just lost his family and is surrounded by thousands of miles of water?’ Probably not.”

Thinking about sounds in the context of literature opens new possibilities. It’s all about homing in on that sweet spot, Anderson said.

“I am not going to say that is better than other modes of teaching, but when that happens in a classroom, you can see that students are discovering something new, and they have spent a lot of time in classrooms where they don’t get that feeling.”

By Gary Moss, The Well