Through a fall 2018 research-intensive QEP class, students interviewed nine descendants of a 1921 North Carolina lynching victim at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Their oral history interviews will be archived at the museum and in Wilson Library as part of the ongoing Descendants Project, which will capture the stories of living family members of lynching victims and help to memorialize those victims.

In late November, a few minutes before midnight, a busload of 28 tired and exhilarated undergraduate students pulled into the Morehead Planetarium and Science Center parking lot after a trip to Washington, D.C. They had participated in an experience that one student said she would remember for the rest of her life.

As Glenn Hinson, associate professor of anthropology and folklore, who accompanied the students on the trip, said “much learning and healing happened that weekend.”

Students in Hinson’s fall “Southern Legacies: The Descendants Project” class interviewed nine descendants of 1921 Warren County lynching victim Plummer Bullock at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The family members represented three generations, with the oldest being 87. The mothers of the two oldest descendants were sisters of Plummer and Matthew Bullock, who were brothers. The oral histories of the two women, as well as their children, grandchildren and nieces, will be archived at the museum and at UNC’s Wilson Library, and copies will be given to the descendants.

The trip was the culmination of a semester spent trying to track down people and stories that have been lost over time. It’s a passion for Hinson and his students, who first began reaching out to descendants of lynching victims and inviting them to tell their stories in 2016.

“One student told me, ‘So much wisdom dropped in my interview that I walked away forever changed,’” said Hinson, whose Alumni Hall office is stacked with audio equipment. “I felt like I was watching stones being dropped in ponds. You could see the ripples in students’ minds and bodies and feel what they were feeling, because they were talking about racial violence and trauma and also hearing absolute stories of community resilience.”

Twenty-year-old Plummer Bullock and his cousin Alfred Williams were both lynched by a white mob on Jan. 23, 1921, in Warrenton after a fight broke out following an argument in a store. Matthew Bullock escaped and eventually made his way to Canada, where he successfully fought extradition. Other family members fled North Carolina and relocated to the D.C. area.

Two copies of Plummer Bullock’s death certificate were filed, one with Warren County and another with the state of North Carolina. Only the state certificate lists his cause of death as lynching. In the new year, Hinson and a group of students will be working with the Warren County NAACP to get the local copy changed, and to assist with plans for a memorial for the victims in Warren County.

Fieldwork in Warren County and D.C.

Although Hinson and students in previous classes had been working on locating descendants of lynching victims for a couple of years, this was the first semester dedicated to a new research-intensive course focused on that topic. The opportunity allowed them to develop a long-term collaboration with Warren County.

Hinson received funding from Carolina’s Quality Enhancement Plan, or QEP, to develop a Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE), which focuses on bringing novel research projects and experiential learning into undergraduate courses.

Dorothy Colón, a junior psychology major from Raleigh, said meeting the family members of Plummer Bullock in D.C. “felt like the impossible became possible.” Locating descendants of lynching victims is often difficult and involves probing a paper trail of newspaper accounts, marriage and death certificates, military records, obituaries, cemetery records and census data. Plummer Bullock’s name was not even recorded on the U.S. Census.

“Some of the descendants we met were not aware that a lynching had occurred in their family,” said Colón, who is pursuing a minor in Hispanic studies. “When we were trying to find the descendants, the process was made much harder because accurate and consistent names and death certificates were not always available.”

Brianna Albritton, a senior psychology major from Mebane, said the D.C. trip was the culmination of the collective work of her classmates, for whom she has “so much love and respect.”

“Feelings of solidarity, hope and gratitude were overflowing [that day],” she said. “All of the descendants were such incredible, strong people and to know that they are directly related to such a tragic event is so mind-boggling.”

Meagan Watson is a junior anthropology and public policy major from Lucama, a small town near Wilson. She said also seeing the town where the lynching took place put things into context.

“When you’re reading about it, you’re kind of removed from it, but then you visit Warren County and see the store where the confrontation happened that led to the lynching and the jail where the men were held,” said Watson, who is pursuing a minor in social and economic justice. “It was really impactful.”

Hinson first became interested in telling these stories after the release of a 2015 report by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a nonprofit based in Montgomery, Ala. Lynching in America, Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (now in in its third edition) documented more than 4,400 lynchings between 1877 and 1950, including a map that shows African-American lynching victims by state. It became the “textbook” for the class last semester.

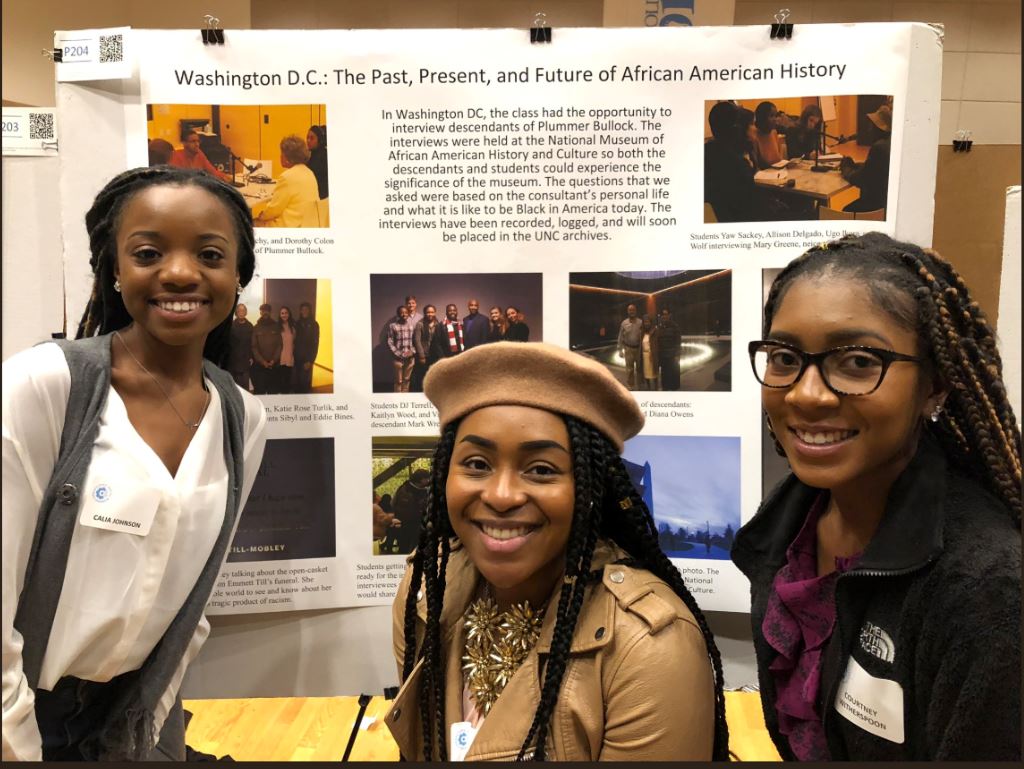

Student teams from the class presented their research at the fall end-of-semester QEP Expo held in the Frank Porter Graham Student Union.

Continuing the project

Watson is part of an Undergraduate Research Consultant Team of four students who will continue research on the project this semester under Hinson’s guidance. URCTs are small interdisciplinary teams of students who receive funding from the QEP and the Office for Undergraduate Research to develop well-executed, one-semester projects under the mentorship of a faculty adviser.

Her team will work closely with the NAACP and other leaders in Warren County to focus on the memorialization and remembrance part of the project.

They’ll help family members try to get the local copy of Plummer Bullock’s death certificate in Warren County changed to indicate lynching as the cause of death. EJI has also created a Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in downtown Montgomery, and students will visit those sites. They will work with the organization to determine the exact location of the lynching with the goal of erecting a historical marker as well as a memorial. EJI is creating a stone memorial for each county in which a lynching occurred. (Learn more about EJI’s Community Remembrance Project and monument placement initiative here.)

One of the team members is a photographer, so she will document their work.

“We’ll also go back to D.C. to look in the National Archives, because they actually have Warren County’s local NAACP records from that time, and they have stories about the lynching that have never been told before,” Watson said.

Students said they walked away from the class changed by the experience, but Hinson said it was meaningful for descendants, too. He shared a handwritten thank-you note he received shortly after the class visit to D.C. from Louise Owens, one of the elder descendants of Plummer Bullock. Other relatives have asked, “Are you coming back next year?”

“If there are to be acts of reconciliation and reparation, it has to begin with people challenging the ‘official’ histories,” Hinson said. “Because if it’s not remembered and discussed, complacency will reign.”

Colón said she hopes “future classes will pick up where we left off.”

“Last semester’s anthropology course and the students who led the research have started unearthing history, and the digging must reach deeper and wider.”

By Kim Weaver Spurr ’88, College of Arts & Sciences

Read an Endeavors magazine story from UNC Research which provides more information about the work of Hinson and assistant professor of American studies Seth Kotch to tell the stories of lynching victims.