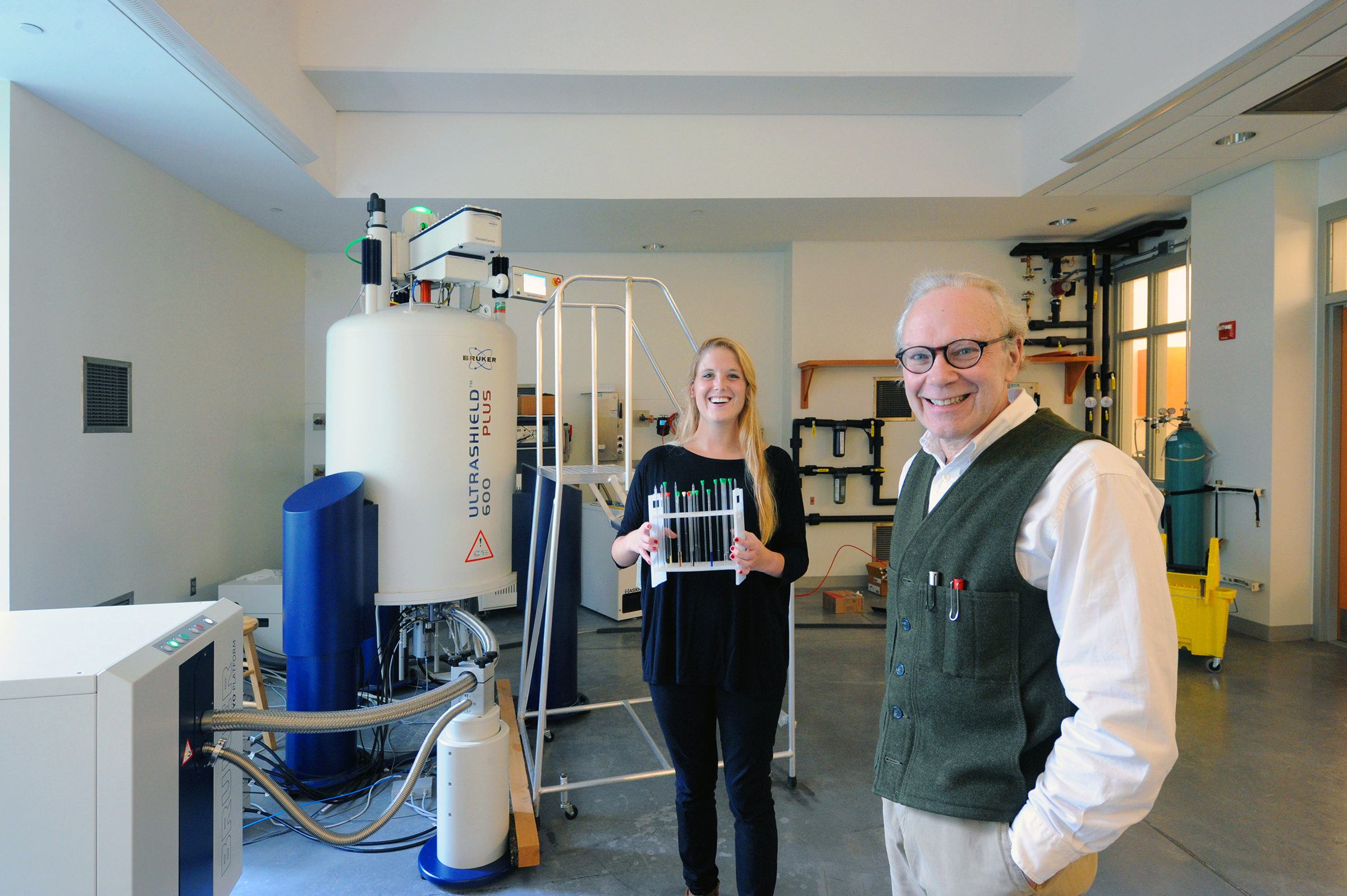

Chemistry professor Gary Pielak, a recipient of a UNC Lifetime Mentoring Award, includes undergraduates and graduate students as co-authors on his research, like in a recent paper in PNAS on how protein shape modulates crowing effects in the cell. He says working with students is the best part of his job.

In 1973, Gary Pielak was set on becoming an auto mechanic, but his parents insisted that he attend college. These days, while the UNC-Chapel HIll Kenan Distinguished Professor of Chemistry works on his 1973 British racing green MGB as a hobby, his day job is working to understand protein-protein interactions and how these signals can misfire, causing human disease.

Protein-protein interactions transfer information within cells. These interactions are important because, as Pielak explained, “Understanding how proteins interact with each other under authentic cellular conditions is essential to designing the new generation of therapeutic agents for treating human diseases such as cancer, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.”

Understanding these interactions has posed a tremendous challenge to scientists because simulating the crowded and complicated conditions inside a cell is difficult, so studies are conducted in test tubes. Pielak and his team are working to overcome that challenge with a bold plan to measure proteins in living cells using high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

A cell’s interior is packed with proteins and other molecules. This crowding pushes molecules together, driving the interactions to sustain the cell, and work from his laboratory shows that chemical interactions between these molecules must also be considered.

Think of a crowded elevator. When many people are inside, everyone makes themselves as compact as possible — they alter their shape. If someone enters the crowded elevator having just had a snack of Limburger cheese, people may back up a bit, repulsed by the smell. However if someone enters with half a dozen Krispy Kreme doughnuts, people are likely attracted. Parallel responses occur within cells; the compaction arises from so-called hard-core repulsions while the cheese and doughnuts represent repulsive and attractive chemical attractions, respectively.

In a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the Pielak team reported on the influence of protein shape under crowded conditions. Their work confirmed a long-held scientific prediction about the effect of crowding on these different interactions: protein shape modulates the influence of these hard-core repulsions and chemical attractions. Their findings pave the way for further experiments in the cellular environment.

Typical of many of his papers, Pielak’s co-authors on this one included an undergraduate, two graduate students and a nuclear magnetic resonance lab director. Successful mentoring of his students shapes their approach to science.

“Gary always made sure that we had well formulated hypotheses, and that these hypotheses were efficiently addressed by smart experimental design,” said Gerardo M. Perez Goncalves, the undergraduate co-author who began graduate school at MIT this fall. “The deep insights I gained into understanding the ‘why and how’ to do experiments have proved to be extremely valuable and gave me a foundation on which to build more scientific knowledge.”

Pielak’s mentoring skills were honored when he received the 2017 UNC Lifetime Mentoring Award. Jeffrey Johnson, UNC chemistry department chair, wrote in his nomination letter, “His two most highly cited papers have undergraduates as first authors. Gary supports and challenges his students to [reach] new heights, both for them and for science. Gary stays in touch with most of these students, who continue to seek his advice many years after leaving Chapel Hill.”

Indeed, Pielak’s CV lists over 100 present and previous undergraduate, graduate, postdoctoral and high school students he has taught or mentored.

Pielak describes listening as the most important key to successful mentoring. He meets with each lab member every Wednesday for 30 minutes. The lab group meets weekly to present research and discuss problems and possible solutions and sometimes serves as a practice session for upcoming talks by lab members. “As a scientist, you have to be able to present your data, so we practice talks at the group meeting, and offer feedback and suggestions,” Pielak said.

He cites working with students in the lab as the best part of his job. “Students are what pushes the research and me in new directions. They’re what make this job worthwhile. I just have to listen to the ideas, and we go off in fruitful directions.”

Thomas Boothby, a biology postdoctoral research associate, did just that. Boothby studies tardigrades, microscopic animals with amazing survival abilities. Boothby approached Pielak, explaining that he needed a protein chemist for his tardigrade work, and they were off.

These tiny eight-legged tardigrades, often called “water bears,” reside on land, in oceans and fresh water. They survive extreme heat, cold and dehydration or dessication. Their survival ability comes from intrinsically disordered proteins or IDPs. IDPs have adaptive structures that make them important to cellular signaling and regulation.

“These tardigrade proteins are amazing because you take them out of tardigrades and they still protect other proteins in the dry state,” Pielak said. “We’re just beginning to get into that research.”

But research partnerships and shaping future scientists are not the only mentoring roles Pielak undertakes. For Shannon Speer, a third-year graduate student in his lab and a PNAS co-author, there’s another: professional development. She says that Pielak has been committed to her professional growth as she has taken on leadership roles in UNC’s Science Policy Advocacy Group, Women in Science, and Advocates for Minorities and Woman in Science and Engineering.

“Gary has taken an active role in supporting me and my goal of teaching at a small university,” Speer said. “His interactions with all graduate students ensure me that he views my success as his top priority. I know that I can count on Gary not only as my current graduate adviser, but also as a lifelong mentor.”

Pielak’s decision to come to UNC 29 years ago continues to be a dream job. “The UNC chemistry department was and remains most collegial: big brains, small egos. I just love science. I like seeing the light go on in a student’s head. I’m so lucky.”

Just like his students.

By Dianne Gooch Shaw ’71