About 45 art, art history and classics students, hairstylists, costume designers and a few curious staff and community members crowded into the Ackland Art Museum’s ancient art gallery on a recent Friday afternoon, eager to learn how to replicate ancient Roman hairstyles.

The free workshop, led by hairstylist and “hair archaeologist” Janet Stephens, was part of a new interdisciplinary course called Art and Fashion from Rome to Timbuktu, taught by Victoria Rovine (art and art history) and Herica Valladares (classics). The class is one of six created through an initiative by Dean Kevin Guskiewicz of the College of Arts & Sciences to encourage cross-disciplinary, team-taught classes. Stephens also gave a public lecture as part of her campus visit.

When she and Rovine received the grant for the class, Valladares knew she wanted to invite Stephens, whose hands-on workshops and YouTube videos are popular. “Classics can come across as an old-fashioned discipline that doesn’t appeal to modern students. I saw this workshop as a really wonderful way to reach out,” Valladares said.

Valladares first met the Baltimore hairstylist when, as a classics faculty member at Johns Hopkins University, she read over Stephens’ research before it was published. The experimental archaeologist used her hairstyling know-how and painstaking examinations of ancient art, artifacts and Latin texts to prove that the hairstyles of ancient Roman women were their own natural locks and not wigs, as had been previously assumed. Stephens demonstrated how an ornatrix (hairdresser) could have sewn even elaborate natural hairstyles in place with a special acus (needle) threaded with wool. Previous archaeologists had not been able to correctly identify the purpose of these larger, thicker needles, made of bone or glass that would have been impractical for sewing.

This is the bust that launched Stephens’ career as an “experimental archaeologist.” One look at the ornate ‘do worn by Julia Domna, the Syrian-born wife of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus (AD 193–211), and the hairstylist couldn’t wait to get home and see if she could replicate it on a mannequin.

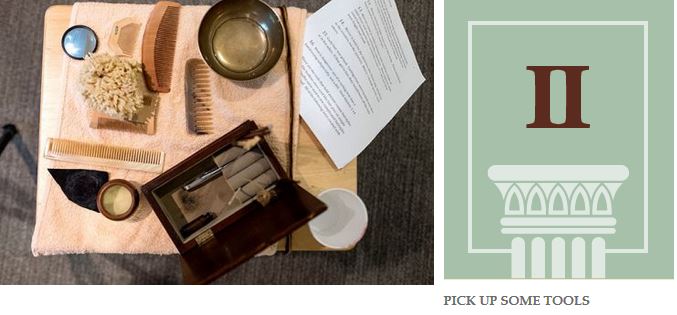

Stephens bases her toolkit on “beauty cases” found in the tombs of ancient Roman women: combs, water bowls and pomades (to make the hair easier to braid), shiny metal “mirrors” and the acus, a large sewing needle. The last item solved two historical mysteries: how was this strange tool used and how did those Roman ladies keep their gravity-defying hairdos in place without hairspray or bobby pins?

Well, not just any head. These styles require very long (preferably waist-length), unlayered hair. In well-to-do Roman hous holds, Stephens explained, a slave called an ornatrix did the hairstyling, with two slave

assistants. But the hairstyles themselves were copied by all classes of women, with the help of friends and relatives. Women had their hair done in the home, not at a public salon. Men, especially those who didn’t trust their own slaves with a razor to their necks, usually went to a barbershop.

To replicate ancient Roman hairstyles, Stephens studies portraits—sculptures and coins—looking at hairlines, part lines, whether the hair moves forward or back.Roman women wore symmetrical hairstyles, usually with a center part, she said. Because they were afraid more fragile renditions would chip or break, sculptors often made braids and curls that were much thicker than real ones. “Hair is much neater on the statue,” she said. “Pity the poor sculptor trying to reproduce hair. Hair is like smoke. It moves. It swirls.”

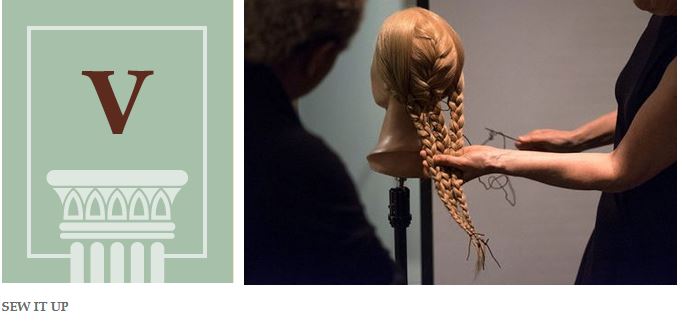

This step was Stephens’ breakthrough. Julia Domna’s thick, coiled braids reminded Stephens of a braided rag rug—a craft created by braiding cloth, coiling the braids in flat oval or round shape and sewing them together to hold them in place. She realized that’s exactly what the ornatrix had done with the acus. First, she looped wool yarn at the end of a braid to anchor it, then threaded it through the braids to create and secure styles much thicker, wider, taller and ornate than would seem possible.

At the end of Stephens’ workshop, the six women whose hair was styled came to the front of the room. All the stylists had been working from the same template, but because of different hair textures and lengths and varying braiding methods, none of the coifs looked exactly the same. “The woman brings her own hair to the style,” Stephens said. “So everything—from its texture, its length, its thickness, its color—will add a bit of variety that is unique to her.”

By Susan Hudson, University Gazette