Listen to a UNC “Well Said” podcast interview with Mitch Prinstein.

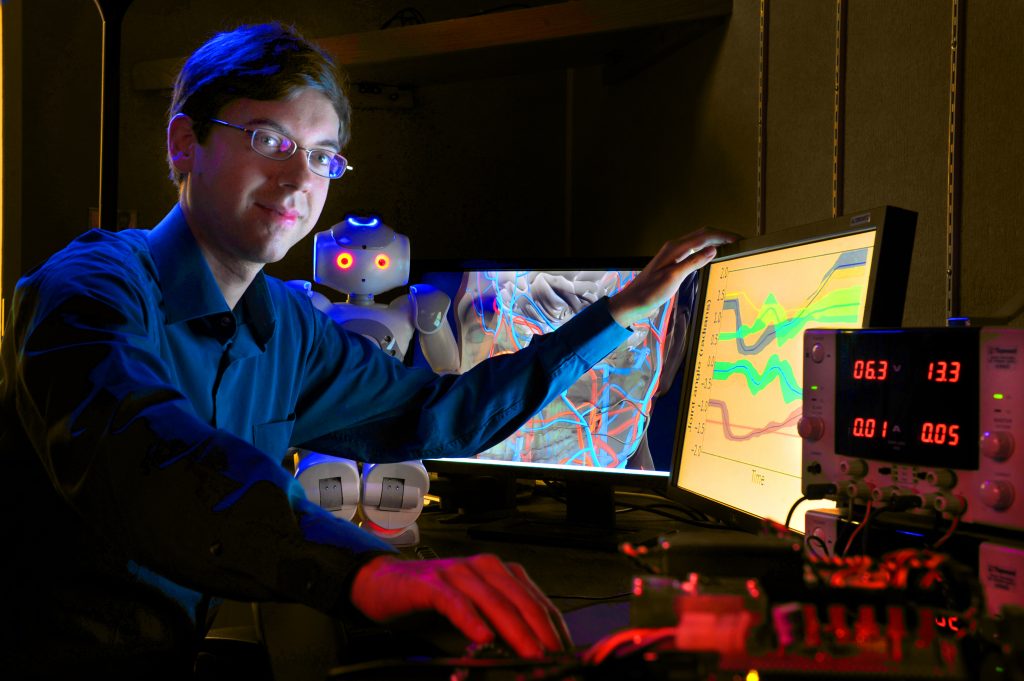

UNC psychologist Mitch Prinstein has been interested in the subject of popularity for decades. His latest book, Popular: The Power of Likability in a Status-Obsessed World (Viking, June 2017), examines why popularity plays such a key role in our social development, our eventual happiness and even our longevity. We recently sat down with Prinstein, the John Van Seters Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience in the College of Arts & Sciences, to talk about the book, which has been gaining a lot of media attention, with features in media outlets including The New York Times, Money, Scientific American, Salon, The State of Things, The London Times, The Atlantic and more.

Q: How did you gain an interest in the science behind popularity?

A: I found myself very interested in the subject of popularity even as a kid, as I witnessed the social hierarchy all around me. Then when I went to graduate school and I began to do work as a clinical child psychologist, it became so clear to me that kids’ relationships with peers are powerful predictors, not only of their success in childhood and adolescence, but also their long-term adult functioning. We spend so much time focused on how to help kids learn to study well and eat well, but it turns out that this is a predictor that’s really important, and we don’t spend as much time talking about it.

Q: You unpack a lot of research in the book, but you keep coming back to a key point — the difference between two types of popularity: status (how well known, widely emulated and powerful we are) vs. likability (being kind, empathetic, selfless and sensitive to other people’s feelings). Why should we care about this distinction?

A: It’s an extremely important difference to care about in 2017, more so than in in any other time in our culture really. We are a world obsessed with status right now. We have become a celebrity-obsessed, status-seeking culture.

Q: Has technology had a lot to do with that?

A: I think so. Social media now makes it all too easy for everyone to try and gain high status with a single mouse click. That’s fun and there’s a place for that — but there’s reason to be fearful, too, because it’s starting to replace our desire to build actual real connections with people. There’s some research that suggests that people feel more isolated now than they have in decades. I think it’s because they’re pursuing the wrong kind of connections.

Q: Preschool kids seem to get it — that the most likable kid is the one you want to be around. But you point out that begins to shift in adolescence, when we become hard-wired to crave status. How do you fight against that?

Q: Preschool kids seem to get it — that the most likable kid is the one you want to be around. But you point out that begins to shift in adolescence, when we become hard-wired to crave status. How do you fight against that?

A: In adolescence, that part of our brain makes us crave popularity in the cheapest, easiest, fastest way we can. And that mirrors what other species do — those who are the most dominant, who get the most attention — have the most popularity. It’s up to us as adults to make that shift and to realize you can activate the same areas of the brain by caring about others, by expressing empathy toward others. We’re facing a kind of a relationship crisis in a way. The world has made it too easy to focus on the wrong kind of popularity.

Q: Do parents have a role in how this plays out for kids? What can they do?

A: Absolutely. We’re counting on parents to be the ones to remind kids about the importance of likability rather than status. Kids are bombarded with messages in the media to become social media famous. The lesson they may extract is that their value as a human being can be measured by the number of their followers on Instagram. Parents need to remind kids that even though the world is giving them a very clear message that status matters, it ultimately is not what matters, and in fact it will lead to long-term negative outcomes.

Q: You stress in the book that popularity and unpopularity can literally affect your health. Can you elaborate?

A: Those who are isolated have a much higher risk of physical disease and even death. But the benefits of popularity are stronger for likability than the type of popularity based on status. In fact, likable people who have high quality relationships are twice as likely to survive as those who are disconnected. The only factor comparable to unpopularity as a health hazard is smoking.

Q: If you were giving a TED talk on this, what are the key takeaways?

A: We are biologically built to have our adolescent experiences continue to affect and influence us every day, even in ways we don’t realize. Those memories from high school create a filter that affects the way we see every one of our social interactions today. That 16-year-old teen who may or may not have been the most popular person sneaks up on us at home and at work. The book provides an opportunity to understand how that works and how to overcome that.

Q: So … we have to know. Were you popular in high school?

A: I was this nerdy, very late-to-develop kid. In terms of status, I had no chance — but I think I was likable enough, and ultimately the power of likability is what really matters. Those who are likable are given extra opportunities and resources that offer a durable life advantage. Status can do that as well, but in a far more superficial way. That’s why I hope this book helps people recognize the difference between likability and status, and they begin to focus on the one most likely to help them in the long run.

— Interview by Kim Spurr, College of Arts & Sciences