Growing up in rural North Carolina during the Great Depression, Grover Elmer Murray, Jr. understood the importance of sharing resources with those in need.

This led him to establish the Dr. Grover Elmer Murray, Jr. Field Camp Scholarship at UNC-Chapel Hill, a place where he was once a student in need when financial aid and student loans did not exist.

Since 1995, this endowed scholarship has supported nearly a dozen undergraduate students in the geological sciences department attending field camp, an intensive outdoor course that allows students to use their classroom and lab training to solve geological problems in the field.

While a professor at Louisiana State University (LSU), Grover led a student field camp trip. He saw how important it was for students to experience studying real rock formations and conducting analyses and also how difficult it was for some students to afford it. He felt strongly that no geology student should go through their undergraduate career without attending field camp.

Grover saw his gift serve its intended purpose before he died in 2003.

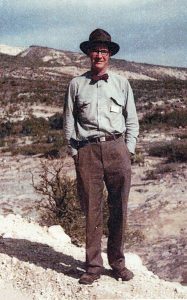

Grover graduated from UNC with his bachelor’s degree in geology in 1937, but considered himself a student of the subject all his life. He wore many hats throughout his 86 years: professor, consultant, university president, a loving husband and father and one of the preeminent geologists of the 20th century.

Humble beginnings

Born in 1916, Grover grew up in Newton, N.C., where his parents encouraged his love of the outdoors. They wanted him to go to college, despite their financial circumstances, and sent him to UNC with $100 in his pocket.

What Grover’s parents couldn’t give him financially, they made up for by instilling manners and stressing the importance of work ethic, traits that greatly benefited him at UNC and beyond.

To earn money while in school, Grover worked in a store that sold things like cigarettes and razors to residents of his dorm and chose to live in the dorm’s unfinished attic at a reduced rate. Grover also worked in the faculty dining hall, a position that showed him the importance of giving back.

A love for geology

Grover developed his passion for geology under the mentorship of UNC professor John Huddle.

“I think it was his first introduction to something that made him think, ‘Aha, I like this!’” his wife Sally said. “He seemed to become aware of how geology works, the coursework, the lab work and the field work. Then here was this marvelous teacher that told him the responsibility of valuing your profession.”

After UNC, Grover attended graduate school at LSU, where he obtained his master’s degree in 1939 and his Ph.D. in 1942. In June 1941, Grover married his high school sweetheart, Nancy Setzer. They had two daughters, Martha and Barbara. Nancy died in 1985.

You’re never too old to learn

Grover began his professional career as a petroleum geologist for Magnolia Petroleum Company in 1941. In 1948, he accepted the offer to be a professor at LSU. He was quickly promoted to chairman of the geology department and in 1963 became the vice president and dean of academic affairs for the entire LSU system.

His accomplishments caught the eye of the board of directors at what was then Texas Technical College, which was looking for its next president. Grover was inaugurated as its eighth president on November 1, 1966.

During his 10-year term,, Grover led the charge on taking Texas Tech from a college to a university; he established a law school, the International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land Studies, and his proudest accomplishment -the School of Medicine.

But he always credited those who supported him in his success.

“I love the fact that he had so much respect for all people.” Sally said. “He always said ‘We had a good ten years,’…He was very aware that it took a strong group of dedicated supporters to bring about success.”

Grover retired as president in 1976 but remained active in the geology world. He stayed involved in his activities, and it was on a field trip with the West Texas Geological Society that he met Sally, a fellow lover of geology from Tyler, Texas.

The two were married on Grover’s 70th birthday.

Grover was never one to rest on his laurels, and spent the later part of his life with Sally continuing to read, travel and most of all, learn.

“He loved to say, ‘You’re never too old to learn,’”, Sally said. “The house was full of books and papers and publications, but that was Grover. He loved to read, he loved to inquire.”

Grover’s travels throughout his life took him everywhere from Antarctica to New Zealand to Peru, but he most loved admiring landscapes in the U.S.

“I’d drive and he would ride with a geologic map in his lap and he’d say, ‘Now we are looking at cretaceous rock,’” said Sally.

Grover traveled and read right up until his death. He left Sally with travel plans of her own, requesting his ashes be spread in five different places: a creek behind his childhood home in Newton, the Mississippi River, a peak in West Texas called El Capitan, Lake Cimarroncita in New Mexico and the Rio Grande River in Big Bend National Park, his favorite place to travel.

It took Sally 12 years to carry out Grover’s wishes, making the Rio Grande her last stop in December 2015.

Leaving a legacy

As for what Grover would tell aspiring geologists and the recipients of his scholarship, Sally believes it would be a message about continuing to learn, staying involved in your field, never giving up no matter the state of the job market and, most importantly, returning thanks.

“A great career isn’t just all one person. Somebody did something to get you on your road, and I think he felt strongly about that,” Sally said. “If you’re successful, you thank those people who helped you be a success.”

Speaking for both herself and Grover, Sally has one message for students who achieve success thanks to the generosity of donors.

“You keep this going.”

by Morgan McPherson ’16