When it comes to maintaining good health, I’ve always considered preventative measures, like a balanced diet and regular exercise, as the best approach: taking proactive steps now will benefit your health later in life.

But what about mental health and mental disorders? Is it possible to prevent a painful and complex condition like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

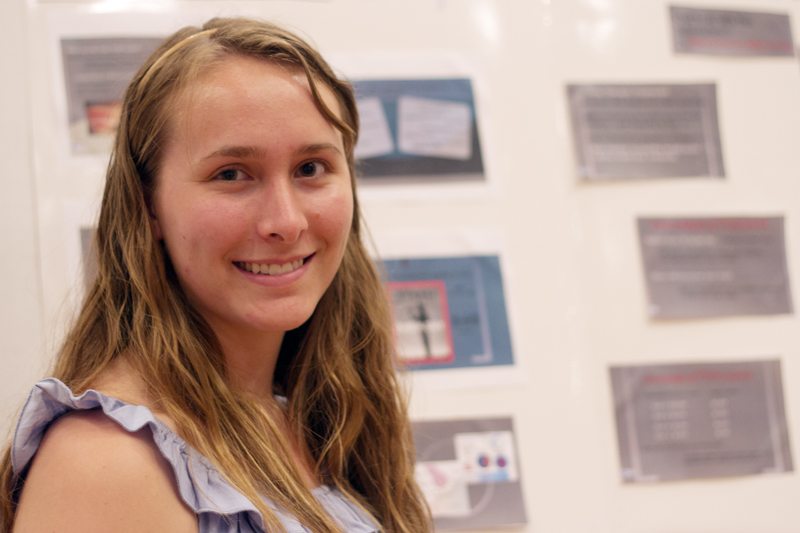

Coertney Scoggin, a Carolina Research Scholar and chemistry major, is trying to answer this question. After reading this article in Time magazine about the rate of active-duty military suicides—one every day in the United States—Scoggin decided to research the causes of PTSD, treatments for it, and even possible methods to prevent the disorder in military personnel.

The problem of PTSD in the military is not new, but the suicide rate is unprecedented. According to Scoggin’s research, more soldiers involved in the war in Afghanistan have killed themselves than have died in combat. In 2012 alone, 295 American military members died in combat, while 349 active members of the military took their own lives. When nonactive military veterans are included, the figures become grimmer: every 80 minutes, according to Time, another veteran commits suicide.

These statistics hit especially close to home for Scoggin, whose father is in the military. Her family lives in southern Maryland, not far from DC and many military bases. Scoggin began her research by reaching out to her family’s connections using social media.

“I just posted something on Facebook that said I was researching PTSD and I’d like to interview a professional about it,” Scoggin says. “Next thing I knew, I had an interview lined up with the national service director of the Disabled American Veterans, Garry Augustine.”

Augustine told Scoggin about the treatments available to veterans suffering from PTSD. Some examples include group therapy, one-on-one counseling, psychotherapy, and therapy dogs. These different therapies are often accompanied by prescription medications including antidepressants, sleep aids, and antianxiety drugs.

Still, the suicide rate among military members is hitting an all-time high. Scoggin started to wonder about other possibilities for combatting PTSD. She picked up the book At War with PTSD: Battling Post Traumatic Stress Disorder with Virtual Reality and read about a drug called propranolol—a substance that could potentially prevent a soldier from developing PTSD altogether.

Propranolol is most commonly used to treat hypertension. Scoggin says some celebrities and politicians take it regularly to relieve stress and anxiety. Studies in Britain and France have shown that propranolol may also be effective in preventing PTSD. But the subjects of those studies had symptoms of PTSD resulting from sexual assault or bad car crashes, not combat in a war zone.

This is how the drug works, according to Scoggin’s research:

During a traumatic event, epinephrine (adrenaline) is released from the amygdala, the center for fear and danger in the brain. It is then absorbed by receptors that create impressions, or memories, of that adrenaline release and the corresponding emotions of fear and danger. Propranolol blocks the beta-adrenergic receptors so that the adrenaline cannot be absorbed, inhibiting the creation of painful memories and PTSD symptoms.

So propranolol essentially blocks the effects of an adrenaline rush—which could make all the difference in a life-or-death situation. What would a soldier do if he or she could not feel the pulsing sensation of fear? Would that put the soldier in more danger?

Or, if it really does prevent painful memories, would it save more lives from the horrors of PTSD and suicide?

Scoggin addresses many of these questions in her research. “It is not a cure,” she says. “But it’s definitely something to be looked at more in depth.” Scoggin also conducted a cost-benefit analysis: a prescription for propranolol for every active-duty military member deployed in a combat zone would cost a small fraction of what the government spends on PTSD treatment.

Scoggin says the drug would undergo rigorous testing before it could be put into use to treat PTSD. But what if there’s a chance it could combat the epidemic of military suicides more effectively than the current treatment options? What if American soldiers didn’t have to bring the horrors of war home with them?

[ Story by Mary Lide Parker, Endeavors magazine ]