“Mommy,” Jennifer Arnold’s three-year-old asked, “what does ‘um’ mean?”

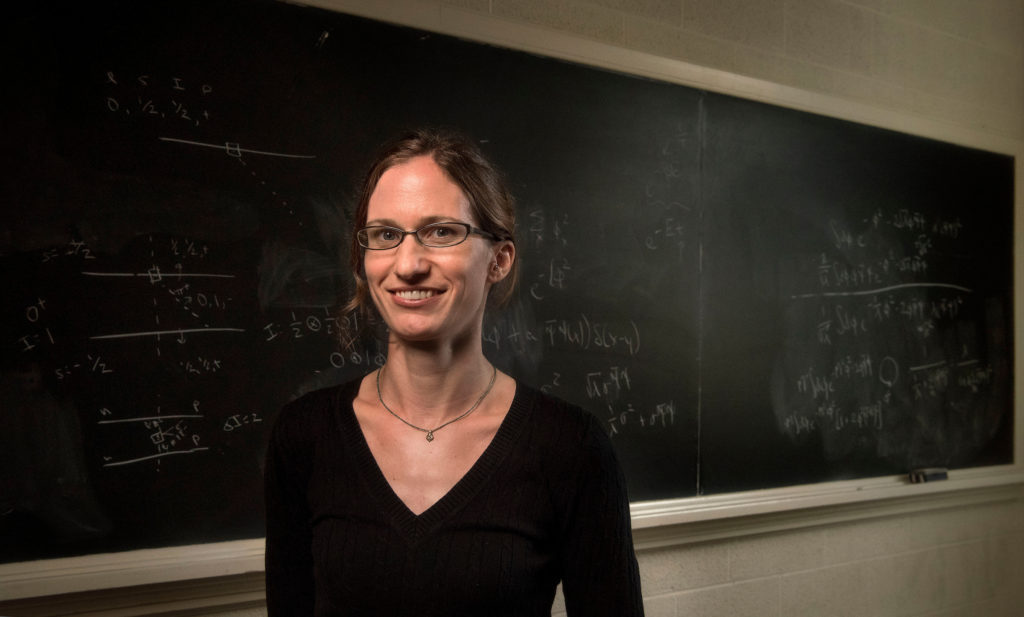

Without knowing it, Arnold’s daughter had hit on a question that Arnold, a UNC psychologist and linguist, was studying in the lab. In our everyday speech, Arnold says, we’re surprisingly inarticulate. We stumble over words, repeat ourselves, run words together so fast that they’re barely intelligible out of context. Amazingly, we manage to get our point across most of the time anyway.

Most of us think of our speech mistakes as meaningless at best, Arnold says—or, at worst, as bad communication. But, as she and her lab found, our conversational missteps sometimes actually help our listeners get what we’re saying.

According to studies, disfluency makes up about 6 percent of our everyday speech. This happens for many different reasons, Arnold says. We might be having a hard time deciding what to say or how to say it. We might be distracted. “In order to show that we haven’t just checked out,” she says, “we’ll throw in a word like ‘um’ or ‘uh.’”

Studies she’s done have shown that we tend to be disfluent when we’re introducing new information into a conversation. It makes sense: it’s easier for the brain to stay on one track than to jump to a new one. The same is true for the person listening. Out of all the things that might be mentioned in conversation, the thing most likely to come up is whatever’s already being talked about. “Your mind,” Arnold says, “expects things to be like they were in the past.”

So we don’t wait until someone’s done speaking to figure out what they’re saying. Before the person we’re talking to gets all the words out, we start guessing how the sentence will end. Arnold thought that one small thing—disfluency—might override our instinct to guess in favor of old information.

In the lab, Arnold’s team fitted subjects with eye-tracking devices and explained that their task was to move objects around the screen with a mouse. A recorded voice gave them an instruction, such as: “Put the grapes below the candle.”

Easy enough. “Now put the camel below the salt shaker.” Listeners who heard this perfectly grammatical sentence took longer to glance at the camel than did listeners who heard a slightly disfluent sentence: “Now put theee, uh… camel below the salt shaker.” The insertion of “theee, uh” before “camel” seemed to signal to the listener that candles were out and a new subject was in.

Arnold’s lab also showed that hearing “theee, uh” made listeners look more quickly at an object that was difficult to name (such as a weird squiggle) than at an object with a known name, such as an ice-cream cone.

Apparently our brains use disfluency as a cue to signal new or unusual information. Why is this a big deal? For one thing, “it overturns the brain’s extremely powerful bias to expect things to be like they were in the past,” Arnold says. If we want to get our point across quickly, we might do better leaving our speech mistakes in than trying to get them all out.

Everyone’s disfluent, Arnold says. It’s a normal part of everyday speech, rather than a signal that communication is breaking down. “When you’re having a hard time saying something, you slow down,” she says. “You pause. That can help the listener, if you’re explaining something difficult.”

Arnold herself talks a mile a minute, but she slows down—seemingly unconsciously—to explain why she studies such minute aspects of language production. “My interest in language is as a window into the human mind,” she says. “I often say to my students that we want to understand this so well that we could build a robot that processes language the way people do.

“Of course, we’re not even close to that yet. But we want to understand the human mind on that level of detail.”

So does Arnold’s daughter get to throw in as many “uhs” and “ums” as she wants? “One time she was trying to tell me a story and she just kept saying, ‘Um… um… um…’ over and over,” Arnold laughs. “I told her, ‘Okay, stop and think about what you’re going to say, and then say it.’”

Jennifer Arnold is an associate professor of psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences. Her disfluency research began and was conducted with colleagues at the University of Rochester.

[Story by Susan Hardy, Endeavors magazine]