Samuel Ray Gates came to the acting game a little later than most. In high school, he was a jock, not a theater kid. He went on to Hampton University in Virginia to get a degree in finance and didn’t see a single play while he was there.

Gates was on the traditional track to success. He moved from his native Detroit to Chicago and worked as a supervisor in a GM warehouse. Sure, he was still a contractor making $13 an hour on the midnight shift, but GM would eventually offer him a permanent job with benefits, better pay and a pension.

There was only one problem. “I was working at a job that I hated,” Gates said.

It was the 1990s economic boom and people with degrees like his were making lots of money. “But that just paled in comparison to what I imagined it must be like to be Denzel Washington,” he said of the Academy Award winning actor, then starring in Spike Lee films Mo’ Better Blues (1990) and Malcolm X(1992).

“I could really see myself doing that,” Gates said, even though he hadn’t been on a stage since kindergarten and had never taken an acting class in his life.

Then Gates’ father, a successful entrepreneur, passed away at age 45. After his dad’s death, Gates discovered that the father who had always wanted him to pursue a career in business had also wanted to be an actor when he was younger.

“That sort of gave me the courage to pursue acting,” Gates said.

Learning to act at ACT

Gates did some research and found that Washington had attended graduate school at the American Conservatory Theater (ACT) in San Francisco. He called and chatted with a kindly registrar who walked the neophyte through the process.

First, the registrar told Gates, he would have to audition. The school was actually holding auditions in Chicago in the next couple of weeks, he added, so Gates should prepare two monologues. Gates had to call back later to find out what a monologue was.

On the day of his audition, “I was so nervous that I drove with my left foot on the gas and the brake because I couldn’t stop my right foot from shaking,” Gates said. Nonetheless, ACT offered him a slot in its summer training program. He would need to fly to the West Coast.

“If I buy a roundtrip ticket, I’ll come back,” Gates reasoned. “So I bought a one-way ticket.” After the summer program, he was admitted to ACT and even got a scholarship.

Gates moved to New York to try acting there. He did get work – on stage and on screen – and in 2005, after attending a Broadway production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, he met Denzel Washington, an actor he still admires.

But Gates, like most actors who aren’t Academy Award winners, needed other jobs to pay the bills. A friend told him about a playwright who was teaching juveniles at Rikers Island prison in New York. He was helping them write poems, songs, stories and plays about fatherhood and he needed an actor to give voice to their words. Gates got the gig.

“It was just electric,” he said. He was hooked. He began participating in Write on the Edge, an educational program of the Manhattan Theatre Club that serves at-risk and court-involved students in New York City and northern New Jersey. Each year the program provides 26 separate residencies, giving more than 500 students the opportunity to write and revise an original play and see it brought to life by professional actors

like Gates.

People often praise Gates for the work he’s done with incarcerated youth, but “the longer you do it, the more you think, ‘I don’t deserve praise for doing that.’ We have a problem. The majority of them look like me. It’s an epidemic,” he said. “They may or may not be getting something out of it, but it’s changing me.”

Gates eventually developed a curriculum based on the plays of Pulitzer Prize winner August Wilson, author of Fences and The Piano Lesson. Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle consists of 10 plays, each set in a different decade of the 20th century, that offer a lively way to look at history unfolding from a black perspective, Gates said. He also taught an introduction to drama workshop at Cristo Rey Brooklyn High School.

Coming to Carolina

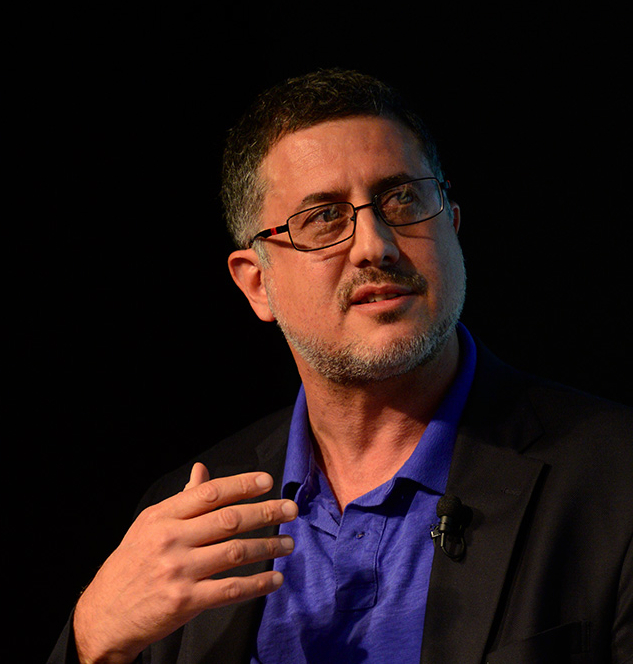

Now Gates is the newest faculty hire in the drama department, teaching introduction to drama for majors.

He was attracted to being a part of Carolina because, like ACT, the University follows a model in which professional actors are the teachers. “It’s one of few programs based on apprenticeship, with students working alongside professional actors,” he said.

As an assistant professor, he looks forward to exchanging ideas with young Tar Heels, just entering the age where they begin to reflect on their lives. “I’m drawn to students who’ve lived a bit,” he said. With his own acting experience on stage and screen, he can also share with them what he has learned about the craft and about the business.

As an actor, he will perform in the Playmakers Repertory Company’s November production of Dot, written by Colman Domingo, a professional acquaintance. In the play, West Philadelphia matriarch Dotty struggles to hold on to her memory, while her three grown children fight to balance care for their mother and for themselves. Gates also plans to explore the ever-expanding southeastern TV and film market from Virginia to New Orleans from his base in Chapel Hill.

“Working at Carolina gives me a great opportunity to further both my acting career and the continuing development of my teaching at the university level where I can nurture students,” Gates said.

This isn’t the first time Gates has come to Carolina, though. When he was in high school, the track coach (who was also his basketball coach) invited him to come with the track team to train at Carolina. Gates played some one-on-one basketball games in Carmichael Auditorium and couldn’t resist showboating a

little bit.

“I practiced the iconic shot by Michael Jordan,” he admitted. Well, who hasn’t?

Story by Susan Hudson, University Gazette