Even after 50 years, the story most people think they know about the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis is not exactly right.

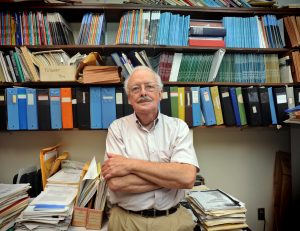

Carolina political science professor Timothy McKeown has devoted much of his career to fixing that, one misperception at a time.

The biggest error, perhaps, is to view it as a 13-day morality tale of virtue triumphing over evil, the stuff that makes for good Hollywood movies. Sure, McKeown acknowledges, even the movies had many of the facts right, but they failed to see – or show – the bigger picture.

“The 13-day narrative is so deeply entrenched in most people’s imaginations, but that narrative is limited, too, because there was so much going on that the story failed to capture,” McKeown said.

Amazingly, most scholarly work also has left out that context, he said.

Another problem with tucking the story into a 13-day span of high drama during October 1962 is that it leaves out much of the vital historical framework needed to explain how and why the crisis started, and equally importantly, how and why it actually ended. Through this wider prism of history, any notion of a neat morality play also falls apart.

If it were a dastardly act for the Soviet Union to position nuclear missiles in Cuba to threaten the United States, then it would be no less reprehensible for the United States to position nuclear weapons at the doorstep of the Soviet Union.

But that’s exactly what the United States did when it positioned short-range ballistic missiles in Turkey in 1960–61.

The positioning of Soviet missiles in Cuba came a year after the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion in which a CIA-trained group of Cuban exiles invaded southern Cuba.

In fact, McKeown said, it was that half-hearted invasion that convinced Soviet leaders that the United States would invade again, and that the second attempt would be far more serious.

A reasonable argument could be made that the Soviets sent missiles to Cuba to prevent such an invasion from happening, McKeown said. And in a roundabout way, it succeeded.

Debunking the ‘Trollope ploy’

The role that Robert Kennedy, U.S. attorney general and President John F. Kennedy’s younger brother, played in the crisis became part of what McKeown calls the “13-day mythology,” but it was what historians believed to be true until the end of the 20th century.

That’s when Sheldon Stern, a historian at the John F. Kennedy Library, published a new summary of transcripts of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council that called that narrative into question, McKeown said.

It became apparent to Stern that the so-called “Trollope ploy” was not at the heart of the solution to the crisis. “Trollope ploy” describes a situation in which a proposal is deliberately misinterpreted by the responder so it is more to that person’s liking, and he or she communicates acceptance of that interpretation of the proposal.

For decades, that term has been used to describe the American strategy of ignoring the private letter from Nikita Khrushchev that Kennedy received on Oct. 26, 1962, in which the Soviet dictator demanded removal of NATO nuclear missiles in Turkey as a condition for removing Soviet missiles in Cuba. Instead, the response was made to the letter Kennedy received the next morning in which the terms for the missiles’ removal involved a pledge from the United States not to invade Cuba.

The problem with the narrative is that Khrushchev made the second offer public to the world – not in a private diplomatic communication, McKeown said.

Once Kennedy heard this offer, McKeown said, he realized that Khrushchev had painted him into a political and diplomatic corner. He understood that “the rest of the world would never understand or accept a situation where the Soviets had to withdraw their missiles from Cuba, but the Americans get to keep theirs in Turkey,” McKeown explained.

“Kennedy thought that would never fly, and that all that remained to be done was to decide how to accept Khrushchev’s offer without making it appear that the Soviets had gotten a good deal,” he said.

Kennedy did not want to appear as if he was reacting to Soviet coercion or that he was weakening America’s military posture in Europe. That’s why publicly, the United States made a pledge it would not invade Cuba, while working out what amounted to an under-the-table promise to remove missiles from Turkey a few months later.

“It has been only in the last decade or so that the preponderance of scholarly opinion has moved in the direction of believing that the implicit missile swap was part of the final settlement,” McKeown said.

“Khrushchev got his way on the Americans withdrawing their missiles, and he got that simply by not saying anything publicly about what the Americans had agreed to.”

Another little-known fact is that the U.S. missiles in Turkey were obsolete, and the Kennedy administration had already planned to remove them before the crisis began. “They were going to be replaced by ballistic-missile-carrying submarines in the eastern Mediterranean that would not be vulnerable to a Soviet first strike,” McKeown said.

Lessons learned

Even during times of crisis, presidents are always looking over their shoulders and thinking about domestic politics and relationships with their allies as well as their adversaries, he said.

“The crisis as a period of very intense bargaining is never divorced from all the other political games that were being played at the time,” McKeown said.

The naval blockade on Cuba, for instance, could do nothing to get missiles out of Cuba that were already there. But it did keep the Soviets from being able to bring in longer-range ballistic missiles.

At the time, polls showed Americans wanted Kennedy to take some action against Cuba, but people were not eager for an all-out war. The blockade fit the bill. It amounted to strong action, but it was not action that would quickly produce casualties, McKeown said.

Another lesson worth noting is that who the president is really matters, McKeown said.

To end the crisis peacefully, Kennedy had to stand firm against the majority of his advisers, who favored military action.

“Most of them thought it would be necessary in the coming week to begin to move ahead with air strikes and an eventual invasion,” McKeown said. “At that point Kennedy essentially said, ‘OK, we’re going to do the swap, but we are going to do it in a delayed, concealed, informal way.’”

Kennedy’s decision to stand his ground showed that not all presidents are creatures of their advisory systems, McKeown said. “A president who has the intelligence and the self-confidence to question and to probe what his advisers tell him is a godsend,” he said.

In addition to nuclear ballistic missiles in Cuba, the Soviets also had anti-ship cruise missiles and other short-range missiles to destroy an invasion. Many of those missiles were equipped with nuclear warheads, McKeown said – but U.S. planners were unaware of this, and never suspected that the Soviets had delegated authority for the use of these weapons to local commanders. (It was a local commander, not the Kremlin, who decided to shoot down an American U-2 reconnaissance plane at the height of the crisis.)

In an interview years later, a Soviet commander of the ballistic missiles aimed at the United States was asked what he would have done if the Americans had attacked his base.

“His response was very simple but rather chilling,” McKeown said. “He said, ‘The normal military response in a situation like that is to reciprocate.’”

So many paths could have been taken that would have led to nuclear war, McKeown said, and at various junctures that nearly happened.

“In the end,” he said, “it was the political pragmatism of Kennedy and Khrushchev, and their willingness to settle for an outcome that satisfied their basic objectives without humiliating their adversary that prevented catastrophe.”