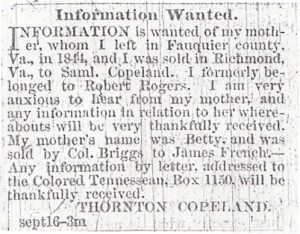

Thornton Copeland placed an “information wanted” advertisement in the Colored Tennessean after the Civil War, 21 years after being sold away from his mother. Just five sparse lines of text make up the ad, and all Copeland knows is his mother’s first name. UNC historian Heather Williams found around 1,200 of these ads in newspapers published by African Americans after the war. She tells these stories of hope and loss, love and longing in her new book, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery (UNC Press, June 2012).

(Read a review of Williams’ book in The New York Times.)

Williams began initially running across the ads while doing research for her dissertation. (She finished graduate school in 2002). After a few months, she had collected 400 of them. She began to piece together slaves’ stories, using census data, journals, letters, government documents and slave narratives. She writes in the book’s introduction that after several years of working on the book, “I am still touched by the stories of people’s stubborn efforts to find their families.”

“I just found them really powerful,” Williams said. “Here are these people, and they are telling you so much in just a few lines. They are telling you about who they lost; sometimes they lost a lot of relatives. Sometimes it’s a son looking for a mother, a mother looking for a child, a husband looking for a spouse. I thought, ‘How can anyone have that degree of hope to still find a person?’”

About one-third of enslaved children in the Upper South experienced family separation through one of three scenarios: sale away from their parents, sale with their mother away from their father — or their mother and father were sold away from the child. Even infants were sold, like 6-month-old Minnie, who was bought for $150 in 1860.

Writes former slave Delia Garlic of Montgomery, Ala.: “Babies was snatched from their mothers’ breasts and sold to speculators. Children was separated from sisters and brothers and never saw each other again. Course they cry; you think they not cry when they was sold like cattle? I could tell you about it all day, but even then you couldn’t guess the awfulness of it.”

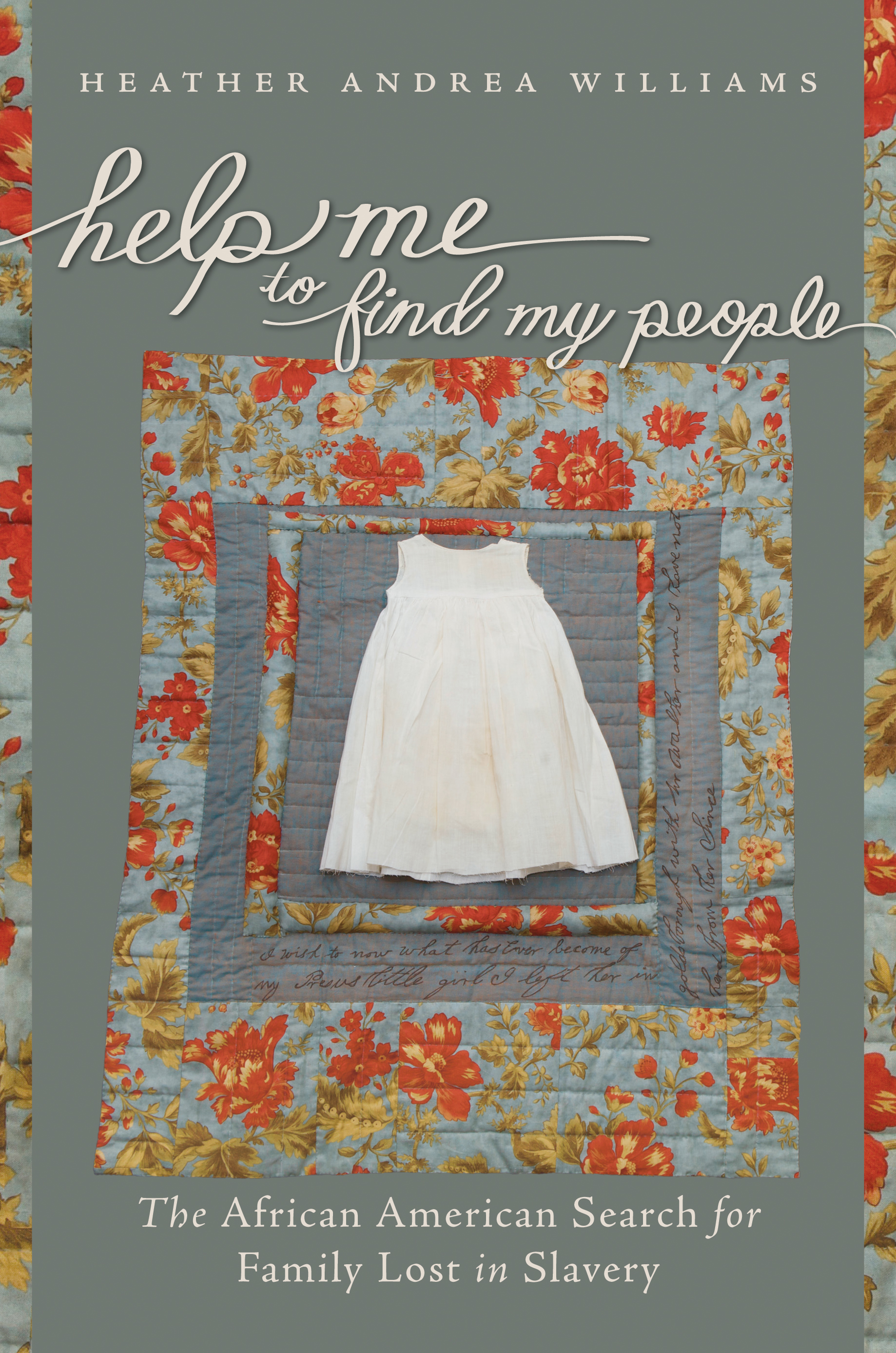

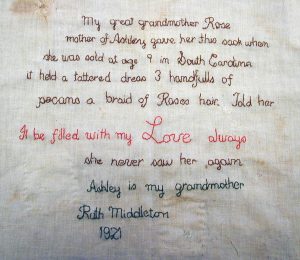

Williams, an accomplished quilter, captures this feeling of parental loss on the front cover of the book, which features a quilt she made with the themes of the book in mind. A pretty blue border featuring red and yellow flowers surrounds a child’s white dress in the center of the quilt. Underneath the dress and around one of the sides of the quilt, Williams traced over the handwriting of a letter from Vilet Lester, a slave who is featured in the book. Lester writes to her former mistress in 1857: “I wish to [k]now what has Ever become of my Presus little girl. I left her in Goldsborough with Mr. Walker and I have not herd from her Since …”

Williams, an accomplished quilter, captures this feeling of parental loss on the front cover of the book, which features a quilt she made with the themes of the book in mind. A pretty blue border featuring red and yellow flowers surrounds a child’s white dress in the center of the quilt. Underneath the dress and around one of the sides of the quilt, Williams traced over the handwriting of a letter from Vilet Lester, a slave who is featured in the book. Lester writes to her former mistress in 1857: “I wish to [k]now what has Ever become of my Presus little girl. I left her in Goldsborough with Mr. Walker and I have not herd from her Since …”

“This is a North Carolina story,” Williams said. “So you’ve got a dress without a little girl, and a mother without a daughter. To me, the cover is sort of inviting you in to the stories that are in the book. And on the back of the quilt, I used fabric with the words, ‘love, courage and faith’ printed on it.”

In talking with a group recently at the Ackland Art Museum about this quilt, Williams said, “One of the sad things about these sources is I never know if [Vilet Lester] got a letter back. I don’t know if she found her child.”

While writing the book, Williams encountered her own feelings of grief and sadness. In October, as the book was going to press, Williams’ father lost his battle with lung cancer. She would work on the book cover quilt at her father’s bedside in Florida, while taking advantage of the good light in his bedroom window.

“In the morning or afternoon, I would sit and quilt, and he would recite poems he learned as a child,” she said. “He would say, ‘It needs more of this or more of that’ … so he helped in the design of the quilt.”

“I had a chance to say goodbye [to my father], and I love you, but a lot of these people did not have that chance.”

Williams divides the book into three sections, addressing the issues of separation, the search and reunification. Other than ads in newspapers, former slaves would also reach out to churches or travel long distances in search of family members. In 1865, a reporter for The Nation met a man who had walked 600 miles from Georgia to Concord, N.C., in search of his wife and children. But most people never found their relatives, for as Williams writes, “too many miles and too many years lay between them.”

In chapter five of the book, instead of just weaving mention of the ads throughout the chapter, Williams wanted to devote a number of pages to laying out the ads, back to back, so “the ads could speak.”

“To encounter the ads as they appeared in the newspapers is to begin to grasp the power and the poignancy of these brief, compelling and urgent dispatches …” she writes.

While writing the book, Williams received support from a semester-long research fellowship sponsored by UNC’s Institute for the Arts and Humanities and a year-long John Mellon Fellowship at the National Humanities Center. And throughout the process, input from her undergraduate students helped to inform the book.

Williams uses one of her history quilts called “My Spirit is Lifted” in her classes; it features the Thornton Copeland ad, along with a number of other primary source documents, such as spirituals, lists of people being sold, a photo of an African American soldier. In her research seminar, students were assigned chapters from the manuscript to critique and analyze. Senior Sally Fry, an intern at UNC Press, designed the cover of the book. Senior Matt Schaefer is credited with the term “self-deification” in reference to Mississippi slave owner Francis Terry Leak removing the word “God” and replacing it with his name, as two of his slaves recited their marriage vows.

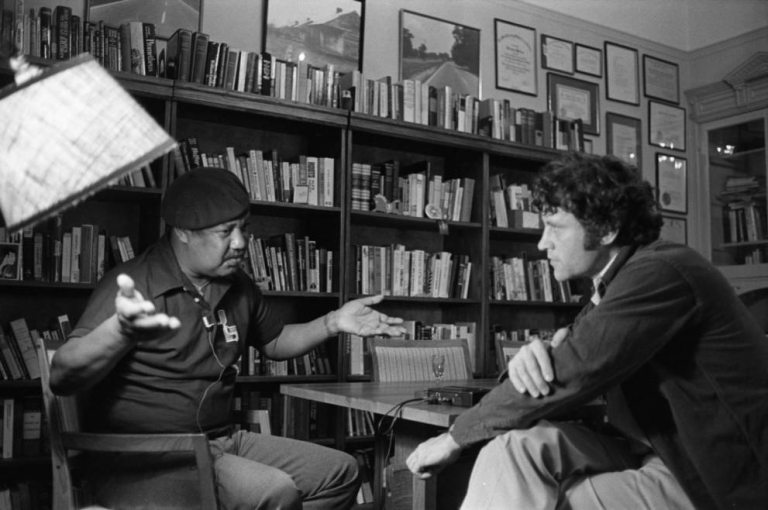

Williams, a native of Jamaica, will start work on her next project soon. She received an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation New Directions Fellowship (see related story) to tell the stories of Jamaican immigrants who came to the United States in the 1950s and ’60s for better jobs and educational opportunities. She plans to produce a documentary film for the project, after she learns filmmaking techniques for the first time.

But Williams said in many ways her current book has no end. It will never really be “finished.”

“For the rest of my life I think I’ll keep finding examples of separation and reunification,” she said. “I want to find more and to dig more.”

Click here for a list of upcoming readings by Williams from Help Me to Find My People.

[ Story by Kim Weaver Spurr ’88 ]